Herbert Wells - A Short History of the World

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Herbert Wells - A Short History of the World» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Жанр: История, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Short History of the World

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Short History of the World: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Short History of the World»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Short History of the World — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Short History of the World», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Russia, Holland and Britain followed in the wake of America. A great nobleman whose estates commanded the Straits of Shimonoseki saw fit to fire on foreign vessels, and a bombardment by a fleet of British, French, Dutch and American warships destroyed his batteries and scattered his swordsmen. Finally an allied squadron (1865), at anchor off Kioto, imposed a ratification of the treaties which opened Japan to the world.

The humiliation of the Japanese by these events was intense. With astonishing energy and intelligence they set themselves to bring their culture and organization to the level of the European Powers. Never in all the history of mankind did a nation make such a stride as Japan then did. In 1866 she was a medieval people, a fantastic caricature of the extremest romantic feudalism; in 1899 hers was a completely Westernized people, on a level with the most advanced European Powers. She completely dispelled the persuasion that Asia was in some irrevocable way hopelessly behind Europe. She made all European progress seem sluggish by comparison.

We cannot tell here in any detail of Japan’s war with China in 1894-95. It demonstrated the extent of her Westernization. She had an efficient Westernized army and a small but sound fleet. But the significance of her renascence, though it was appreciated by Britain and the United States, who were already treating her as if she were a European state, was not understood by the other Great Powers engaged in the pursuit of new Indias in Asia. Russia was pushing down through Manchuria to Korea. France was already established far to the south in Tonkin and Annam, Germany was prowling hungrily on the look-out for some settlement. The three Powers combined to prevent Japan reaping any fruits from the Chinese war. She was exhausted by the struggle, and they threatened her with war.

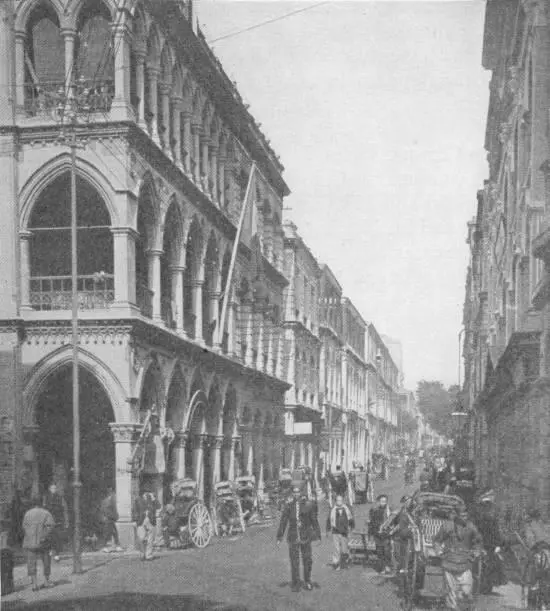

A STREET IN TOKIO

Japan submitted for a time and gathered her forces. Within ten years she was ready for a struggle with Russia, which marks an epoch in the history of Asia, the close of the period of European arrogance. The Russian people were, of course, innocent and ignorant of this trouble that was being made for them halfway round the world, and the wiser Russian statesmen were against these foolish thrusts; but a gang of financial adventurers, including the Grand Dukes, his cousins, surrounded the Tsar. They had gambled deeply in the prospective looting of Manchuria and China, and they would suffer no withdrawal. So there began a transportation of great armies of Japanese soldiers across the sea to Port Arthur and Korea, and the sending of endless trainloads of Russian peasants along the Siberian railway to die in those distant battlefields.

The Russians, badly led and dishonestly provided, were beaten on sea and land alike. The Russian Baltic Fleet sailed round Africa to be utterly destroyed in the Straits of Tshushima. A revolutionary movement among the common people of Russia, infuriated by this remote and reasonless slaughter, obliged the Tsar to end the war (1905); he returned the southern half of Saghalien, which had been seized by Russia in 1875, evacuated Manchuria, resigned Korea to Japan. The European invasion of Asia was coming to an end and the retraction of Europe’s tentacles was beginning.

LXIV

THE BRITISH EMPIRE IN 1914

WE may note here briefly the varied nature of the constituents of the British Empire in 1914 which the steamship and railway had brought together. It was and is a quite unique political combination; nothing of the sort has ever existed before.

First and central to the whole system was the “crowned republic” of the United British Kingdom, including (against the will of a considerable part of the Irish people) Ireland. The majority of the British Parliament, made up of the three united parliaments of England and Wales, Scotland and Ireland, determines the headship, the quality and policy of the ministry, and determines it largely on considerations arising out of British domestic politics. It is this ministry which is the effective supreme government, with powers of peace and war, over all the rest of the empire.

Next in order of political importance to the British States were the “crowned republics” of Australia, Canada, Newfoundland (the oldest British possession, 1583), New Zealand and South Africa, all practically independent and self-governing states in alliance with Great Britain, but each with a representative of the Crown appointed by the Government in office;

Next the Indian Empire, an extension of the Empire of the Great Mogul with its dependent and “protected” states reaching now from Beluchistan to Burma, and including Aden, in all of which empire the British Crown and the India Office (under Parliamentary control) played the role of the original Turkoman dynasty;

Then the ambiguous possession of Egypt, still nominally a part of the Turkish Empire and still retaining its own monarch, the Khedive, but under almost despotic British official rule;

Then the still more ambiguous “Anglo-Egyptian” Sudan province, occupied and administered jointly by the British and by the (British controlled) Egyptian Government;

Then a number of partially self-governing communities, some British in origin and some not, with elected legislatures and an appointed executive, such as Malta, Jamaica, the Bahamas and Bermuda;

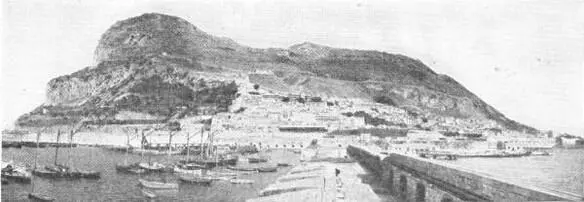

Then the Crown colonies, in which the rule of the British Home Government (through the Colonial Office) verged on autocracy, as in Ceylon, Trinidad and Fiji (where there was an appointed council), and Gibraltar and St. Helena (where there was a governor);

GIBRALTAR

Photo: C. Sinclair

Then great areas of (chiefly) tropical lands, raw-product areas, with politically weak and under-civilized native communities which were nominally protectorates, and administered either by a High Commissioner set over native chiefs (as in Basutoland) or over a chartered company (as in Rhodesia). In some cases the Foreign Office, in some cases the Colonial Office, and in some cases the India Office, has been concerned in acquiring the possessions that fell into this last and least definite class of all, but for the most part the Colonial Office was now responsible for them.

It will be manifest, therefore, that no single office and no single brain had ever comprehended the British Empire as a whole. It was a mixture of growths and accumulations entirely different from anything that has ever been called an empire before. It guaranteed a wide peace and security; that is why it was endured and sustained by many men of the “subject” races—in spite of official tyrannies and insufficiencies, and of much negligence on the part of the “home” public. Like the Athenian Empire, it was an overseas empire; its ways were sea ways, and its common link was the British Navy. Like all empires, its cohesion was dependent physically upon a method of communication; the development of seamanship, ship-building and steamships between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries had made it a possible and convenient Pax—the “Pax Britannica,” and fresh developments of air or swift land transport might at any time make it inconvenient.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Short History of the World»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Short History of the World» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Short History of the World» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.