Herbert Wells - A Short History of the World

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Herbert Wells - A Short History of the World» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Жанр: История, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Short History of the World

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Short History of the World: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Short History of the World»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Short History of the World — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Short History of the World», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In 1824 Louis XVIII died, and was succeeded by Charles X. Charles set himself to destroy the liberty of the press and universities, and to restore absolute government; the sum of a billion francs was voted to compensate the nobles for the chateau burnings and sequestrations of 1789. In 1830 Paris rose against this embodiment of the ancient regime, and replaced him by Louis Philippe, the son of that Philip, Duke of Orleans, who was executed during the Terror. The other continental monarchies, in face of the open approval of the revolution by Great Britain and a strong liberal ferment in Germany and Austria, did not interfere in this affair. After all, France was still a monarchy. This man Louis Philippe (1830-48) remained the constitutional King of France for eighteen years.

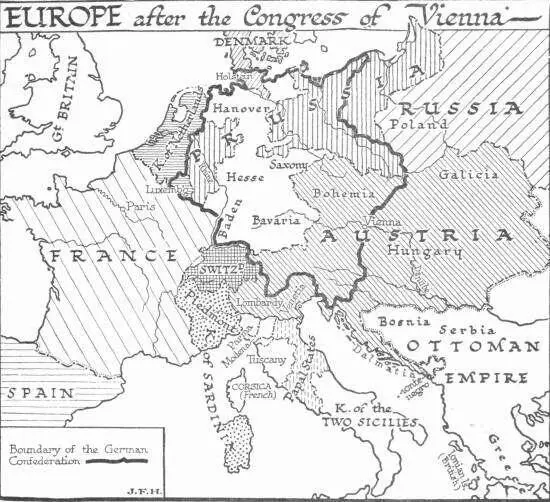

Such were the uneasy swayings of the peace of the Congress of Vienna, which were provoked by the reactionary proceedings of the monarchists. The stresses that arose from the unscientific boundaries planned by the diplomatists at Vienna gathered force more deliberately, but they were even more dangerous to the peace of mankind. It is extraordinarily inconvenient to administer together the affairs of peoples speaking different languages and so reading different literatures and having different general ideas, especially if those differences are exacerbated by religious disputes. Only some strong mutual interest, such as the common defensive needs of the Swiss mountaineers, can justify a close linking of peoples of dissimilar languages and faiths; and even in Switzerland there is the utmost local autonomy. When, as in Macedonia, populations are mixed in a patchwork of villages and districts, the cantonal system is imperatively needed. But if the reader will look at the map of Europe as the Congress of Vienna drew it, he will see that this gathering seems almost as if it had planned the maximum of local exasperation.

It destroyed the Dutch Republic, quite needlessly, it lumped together the Protestant Dutch with the French-speaking Catholics of the old Spanish (Austrian) Netherlands, and set up a kingdom of the Netherlands. It handed over not merely the old republic of Venice, but all of North Italy as far as Milan to the German-speaking Austrians. French-speaking Savoy it combined with pieces of Italy to restore the kingdom of Sardinia. Austria and Hungary, already a sufficiently explosive mixture of discordant nationalities, Germans, Hungarians, Czecho-Slovaks, Jugo-Slavs, Roumanians, and now Italians, was made still more impossible by confirming Austria’s Polish acquisitions of 1772 and 1795. The Catholic and republican-spirited Polish people were chiefly given over to the less civilized rule of the Greek-orthodox Tsar, but important districts went to Protestant Prussia. The Tsar was also confirmed in his acquisition of the entirely alien Finns. The very dissimilar Norwegian and Swedish peoples were bound together under one king. Germany, the reader will see, was left in a particularly dangerous state of muddle. Prussia and Austria were both partly in and partly out of a German confederation, which included a multitude of minor states. The King of Denmark came into the German confederation by virtue of certain German-speaking possessions in Holstein. Luxembourg was included in the German confederation, though its ruler was also King of the Netherlands, and though many of its peoples talked French.

Here was a complete disregard of the fact that the people who talk German and base their ideas on German literature, the people who talk Italian and base their ideas on Italian literature, and the people who talk Polish and base their ideas on Polish literature, will all be far better off and most helpful and least obnoxious to the rest of mankind if they conduct their own affairs in their own idiom within the ring-fence of their own speech. Is it any wonder that one of the most popular songs in Germany during this period declared that wherever the German tongue was spoken, there was the German Fatherland!

PORTRAIT OF NAPOLEON (CORONATION)

(From a print in the British Museum)

In 1830 French-speaking Belgium, stirred up by the current revolution in France, revolted against its Dutch association in the kingdom of the Netherlands. The powers, terrified at the possibilities of a republic or of annexation to France, hurried in to pacify this situation, and gave the Belgians a monarch, Leopold I of Saxe-Coburg Gotha. There were also ineffectual revolts in Italy and Germany in 1830, and a much more serious one in Russian Poland. A republican government held out in Warsaw for a year against Nicholas I (who succeeded Alexander in 1825), and was then stamped out of existence with great violence and cruelty. The Polish language was banned, and the Greek Orthodox church was substituted for the Roman Catholic as the state religion ....

In 1821 there was an insurrection of the Greeks against the Turks. For six years they fought a desperate war, while the governments of Europe looked on. Liberal opinion protested against this inactivity; volunteers from every European country joined the insurgents, and at last Britain, France and Russia took joint action. The Turkish fleet was destroyed by the French and English at the battle of Navarino (1827), and the Tsar invaded Turkey. By the treaty of Adrianople (1829) Greece was declared free, but she was not permitted to resume her ancient republican traditions. A German king was found for Greece, one Prince Otto of Bavaria, and Christian governors were set up in the Danubian provinces (which are now Roumania) and Serbia (a part of the Jugo-Slav region). Much blood had still to run however before the Turk was altogether expelled from these lands.

LVII

THE DEVELOPMENT OF MATERIAL KNOWLEDGE

THROUGHOUT the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and the opening years of the nineteenth century, while these conflicts of the powers and princes were going on in Europe, and the patchwork of the treaty of Westphalia (1648) was changing kaleidoscopically into the patchwork of the treaty of Vienna (1815), and while the sailing ship was spreading European influence throughout the world, a steady growth of knowledge and a general clearing up of men’s ideas about the world in which they lived was in progress in the European and Europeanized world.

It went on disconnected from political life, and producing throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries no striking immediate results in political life. Nor was it affecting popular thought very profoundly during this period. These reactions were to come later, and only in their full force in the latter half of the nineteenth century. It was a process that went on chiefly in a small world of prosperous and independent-spirited people. Without what the English call the “private gentleman,” the scientific process could not have begun in Greece, and could not have been renewed in Europe. The universities played a part but not a leading part in the philosophical and scientific thought of this period. Endowed learning is apt to be timid and conservative learning, lacking in initiative and resistent to innovation, unless it has the spur of contact with independent minds.

We have already noted the formation of the Royal Society in 1662 and its work in realizing the dream of Bacon’s New Atlantis . Throughout the eighteenth century there was much clearing up of general ideas about matter and motion, much mathematical advance, a systematic development of the use of optical glass in microscope and telescope, a renewed energy in classificatory natural history, a great revival of anatomical science. The science of geology—foreshadowed by Aristotle and anticipated by Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519)—began its great task of interpreting the Record of the Rocks.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Short History of the World»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Short History of the World» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Short History of the World» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.