Herbert Wells - A Short History of the World

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Herbert Wells - A Short History of the World» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Жанр: История, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Short History of the World

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Short History of the World: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Short History of the World»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Short History of the World — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Short History of the World», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

THE CHURCH (NOW A MOSQUE) OF S. SOPHIA, CONSTANTINOPLE

The obelisk of Theodosius in in the foreground statue on left

Photo: Sebah & Foaillier

Science and political philosophy seemed dead now in both these warring and decaying empires. The last philosophers of Athens, until their suppression, preserved the texts of the great literature of the past with an infinite reverence and want of understanding. But there remained no class of men in the world, no free gentlemen with bold and independent habits of thought, to carry on the tradition of frank statement and enquiry embodied in these writings. The social and political chaos accounts largely for the disappearance of this class, but there was also another reason why the human intelligence was sterile and feverish during this age. In both Persia and Byzantium it was all age of intolerance. Both empires were religious empires in a new way, in a way that greatly hampered the free activities of the human mind.

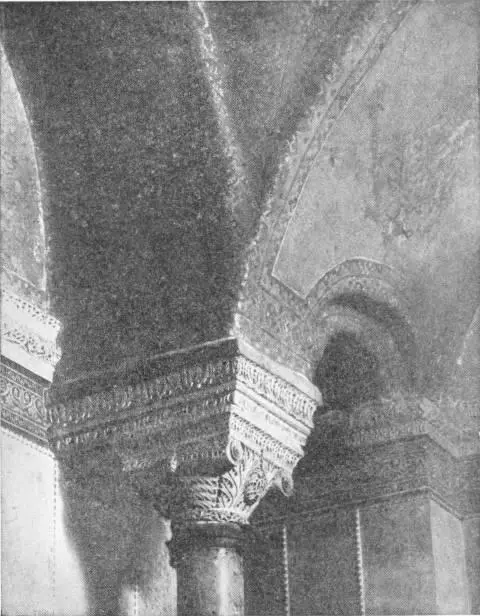

THE MAGNIFICENT ROOF-WORK IN S. SOPHIA

Photo: Sebah & Foaillier

Of course the oldest empires in the world were religious empires, centring upon the worship of a god or of a god-king. Alexander was treated as a divinity and the Cæsars were gods in so much as they had altars and temples devoted to them and the offering of incense was made a test of loyalty to the Roman state. But these older religions were essentially religions of act and fact. They did not invade the mind. If a man offered his sacrifice and bowed to the god, he was left not only to think but to say practically whatever he liked about the affair. But the new sort of religions that had come into the world, and particularly Christianity, turned inward. These new faiths demanded not simply conformity but understanding belief. Naturally fierce controversy ensued upon the exact meaning of the things believed. These new religions were creed religions. The world was confronted with a new word, Orthodoxy, and with a stern resolve to keep not only acts but speech and private thought within the limits of a set teaching. For to hold a wrong opinion, much more to convey it to other people, was no longer regarded as an intellectual defect but a moral fault that might condemn a soul to everlasting destruction.

THE RAVENNA PANEL, DEPICTING JUSTINIAN AND HIS COURT

Photo: Alinari

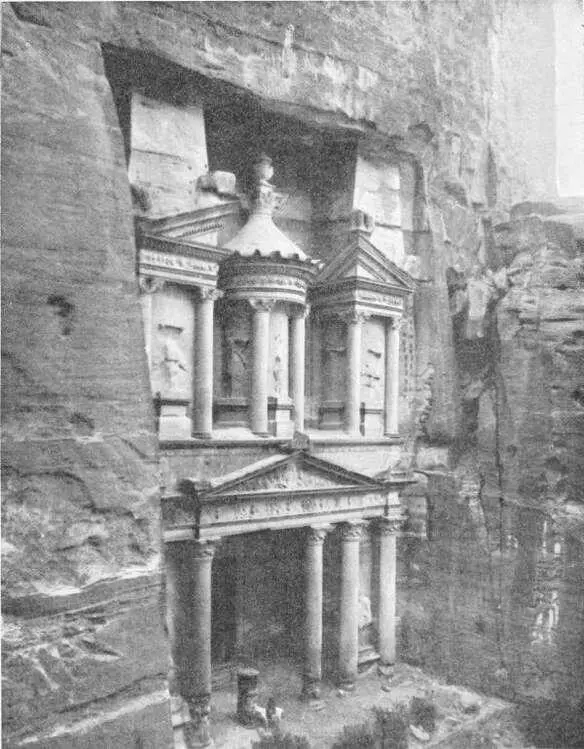

THE ROCK HEWN TEMPLE AT PETRA

Photo: Underwood & Underwood

Both Ardashir I who founded the Sassanid dynasty in the third century A.D., and Constantine the Great who reconstructed the Roman Empire in the fourth, turned to religious organizations for help, because in these organizations they saw a new means of using and controlling the wills of men. And already before the end of the fourth century both empires were persecuting free talk and religious innovation. In Persia Ardashir found the ancient Persian religion of Zoroaster (or Zarathushtra) with its priests and temples and a sacred fire that burnt upon its altars, ready for his purpose as a state religion. Before the end of the third century Zoroastrianism was persecuting Christianity, and in 277 A.D. Mani, the founder of a new faith, the Manichæans, was crucified and his body flayed. Constantinople, on its side, was busy hunting out Christian heresies. Manichæan ideas infected Christianity and had to be fought with the fiercest methods; in return ideas from Christianity affected the purity of the Zoroastrian doctrine. All ideas became suspect. Science, which demands before all things the free action of an untroubled mind, suffered a complete eclipse throughout this phase of intolerance.

War, the bitterest theology, and the usual vices of mankind constituted Byzantine life of those days. It was picturesque, it was romantic; it had little sweetness or light. When Byzantium and Persia were not fighting the barbarians from the north, they wasted Asia Minor and Syria in dreary and destructive hostilities. Even in close alliance these two empires would have found it a hard task to turn back the barbarians and recover their prosperity. The Turks or Tartars first come into history as the allies first of one power and then of another. In the sixth century the two chief antagonists were Justinian and Chosroes I; in the opening of the seventh the Emperor Heraclius was pitted against Chosroes II (580).

At first and until after Heraclius had become Emperor (610) Chosroes II carried all before him. He took Antioch, Damascus and Jerusalem and his armies reached Chalcedon, which is in Asia Minor over against Constantinople. In 619 he conquered Egypt. Then Heraclius pressed a counter attack home and routed a Persian army at Nineveh (627), although at that time there were still Persian troops at Chalcedon. In 628 Chosroes II was deposed and murdered by his son, Kavadh, and an inconclusive peace was made between the two exhausted empires.

Byzantium and Persia had fought their last war. But few people as yet dreamt of the storm that was even then gathering in the deserts to put an end for ever to this aimless, chronic struggle.

While Heraclius was restoring order in Syria a message reached him. It had been brought in to the imperial outpost at Bostra south of Damascus; it was in Arabic, an obscure Semitic desert language, and it was read to the Emperor, if it reached him at all, by an interpreter. It was from someone who called himself “Muhammad the Prophet of God.” It called upon the Emperor to acknowledge the One True God and to serve him. What the Emperor said is not recorded.

A similar message came to Kavadh at Ctesiphon. He was annoyed, tore up the letter, and bade the messenger begone.

This Muhammad, it appeared, was a Bedouin leader whose headquarters were in the mean little desert town of Medina. He was preaching a new religion of faith in the One True God.

“Even so, O Lord!” he said; “rend thou his Kingdom from Kavadh.”

XLII

THE DYNASTIES OF SUY AND TANG IN CHINA

THROUGHOUT the fifth, sixth, seventh and eighth centuries, there was a steady drift of Mongolian peoples westward. The Huns of Attila were merely precursors of this advance, which led at last to the establishment of Mongolian peoples in Finland, Esthonia, Hungary and Bulgaria, where their descendants, speaking languages akin to Turkish, survive to this day. The Mongolian nomads were, in fact, playing a role towards the Aryanized civilizations of Europe and Persia and India that the Aryans had played to the Ægean and Semitic civilizations ten or fifteen centuries before.

In Central Asia the Turkish peoples had taken root in what is now Western Turkestan, and Persia already employed many Turkish officials and Turkish mercenaries. The Parthians had gone out of history, absorbed into the general population of Persia. There were no more Aryan nomads in the history of Central Asia; Mongolian people had replaced them. The Turks became masters of Asia from China to the Caspian.

The same great pestilence at the end of the second century A.D. that had shattered the Roman Empire had overthrown the Han dynasty in China. Then came a period of division and of Hunnish conquests from which China arose refreshed, more rapidly and more completely than Europe was destined to do. Before the end of the sixth century China was reunited under the Suy dynasty, and this by the time of Heraclius gave place to the Tang dynasty, whose reign marks another great period of prosperity for China.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Short History of the World»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Short History of the World» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Short History of the World» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.