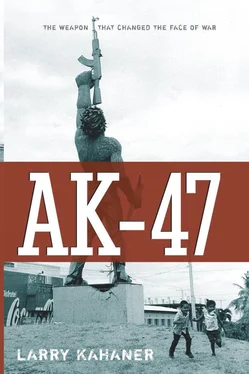

Larry Kahaner - AK-47

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Larry Kahaner - AK-47» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: Hoboken, Год выпуска: 2007, ISBN: 2007, Издательство: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Жанр: История, military_history, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:AK-47

- Автор:

- Издательство:John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Жанр:

- Год:2007

- Город:Hoboken

- ISBN:9780470315668

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

AK-47: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «AK-47»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

AK-47 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «AK-47», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The announcement was met with great fanfare and media attention, but nothing ever became of the scheme. The company simply disappeared, and once again Kalashnikov failed to make money on his invention.

Still, the AK mystique grew stronger. Playboy magazine in 2004 listed the AK-47 as number four in its feature “50 Products That Changed the World: A Countdown of the Most Innovative Consumer Products of the Past Half Century.” That the AK was considered a consumer item, behind the Apple Macintosh desktop computer (number one), the Pill (number two), and the Sony Betamax VCR (number three), was a true indication of the gun’s seminal and long-lasting effect on the modern world. Citing a July 1999 State Department report mentioning the weapon, Playboy ’s editors noted, “In some countries it is easier and cheaper to buy an AK-47 than to attend a movie or provide a decent meal.” The magazine also cited a Los Angeles Times article calling the gun “history’s most widely distributed piece of killing machinery.”

Amid the AK hype, museums began looking at the rifle’s effect on civilization and culture in a more somber and thoughtful way. The Dutch Army Museum in 2003 and 2004 hosted an exhibit on the AK called Kalashnikov: Rifle without Borders that offered visitors a look at multimedia displays on wars in which the rifle had played a deciding role. It showed combat children holding AKs in Africa and elsewhere. One exhibit dramatically illustrated the weapon’s destructive ability by showing a bullet pattern in a porous block. However, even a serious museum could not ignore the Kalashnikov’s pop culture side: attendees saw AKs that had been chrome-plated; others were covered with hot pink fabric and glitter. Even a military-oriented museum could not escape the fact that AKs had become so ingrained in world culture that people adorned them with bright colors, perhaps to defuse some of their power. Kalashnikov himself opened the exhibit amid fanfare. Again, as he had done at every public opportunity in the past, he used the forum to blame politicians for misusing his invention and to absolve himself of the AK’s terrible legacy.

At home, his countrymen were preparing to honor their most famous inventor, too. In 1996, construction of a Kalashnikov museum in Izhevsk began but was suspended due to insufficient funding. With pleas for money throughout Russia and on the Internet, the $8 million Kalashnikov Weapons Museum and Exhibition Center opened on the arms maker’s eighty-fifth birthday in 2004. The museum was designed not only to honor Kalashnikov’s work, but also to jump-start the decaying city of Izhevsk, a boom-town during World War II and the cold war years, now fallen on hard times. Isolated and far from much of Russia’s commerce, the city existed for the production of arms, which it made at the rate of more than ten thousand a day during World War II. Later during the cold war it continued to produce weapons, mainly AKs in great numbers, providing employment and prosperity.

Since the fall of the Soviet Union, with no more AKs being made, Izhevsk officials hoped that the museum would attract tourists. In what was once a top-secret location, closed to outsiders and casual tourists alike, city officials were hoping for urban renewal and better times based on the AK’s star power. During speeches, the mayor conveyed that the museum embodied the strength of the city in that it produced a dependable product, one that worked reliably and was revered worldwide. Like commercial marketers hoping to make money off of Kalashnikov by selling consumer items with his name and endorsement, his adopted town was relying on his celebrity status, too, to help jump-start its economy.

So far, the results have been lukewarm.

PERHAPS THE INVENTOR’S GREATEST chance at financial success came in 2003, when British entrepreneur John Florey was looking for his next big thing. Florey reasoned that Russia was known for its vodka, the way France was known for wine, the Caribbean for rum, and Scotland for scotch whiskey. Russia was also known for producing the AK, and the Kalashnikov had already achieved global cult status. For Florey, the mix of Russia’s favorite spirit and favorite celebrity seemed the perfect concoction. Over dinner one evening, the idea of Kalashnikov’s AK and vodka seemed like a sure shot.

Florey had been a representative for chess champ Gary Kasparov and understood how to promote Russian culture. He had also helped to establish the Moscow Business School, so he was introduced to Kalashnikov in 2001 through the school.

Kalashnikov was interested albeit wary of the idea. He had been burned several times before. The failure of Kalashnikov’s first excursion into the world of vodka branding was not lost on Florey, who approached this project with a showman’s vision for big, bold promotions but without leaning too heavily on the gun angle. He believed that the previous vodka deal did not “extend” the Kalashnikov brand. He also brought a solid business plan. Kalashnikov was named honorary chairman of the “Kalashnikov Joint Stock Vodka Company (1947) plc.” and was to receive a small equity stake and 2.5 percent of net profits for using his name and likeness on the bottle. A 1947 picture of a young and vibrant Kalashnikov was etched into the bottles, and non-rolling shot glasses, invented by Kalashnikov himself for the Russian navy, were slated for use at bar promotions.

Florey assembled an all-star cast including David Bromige, the creator of Polstar Vodka, an Icelandic spirit that played on the motto “Strength Through Purity” along with a polar bear logo. Bromige also was a director of Reformed Spirits Company, owners of Martin Miller’s Gin, a product that had received a lot of attention for its citrus, pear, and clove flavors in Icelandic glacial water, all contained in a hip, angular bottle that bartenders liked to handle as they imitated Tom Cruise’s dexterous motions in the movie Cocktail . Although the brand had come into existence only in 1999, it boasted using “England’s oldest copper still.” With the opening of the former Soviet Union, vodka was growing more popular in Europe and North America as venerable vodka makers like Stolichnaya, Absolut, and Finlandia (the last two were not from Russia) were wooing younger drinkers with offbeat flavors, edgy bottles, even edgier advertisements, and higher prices that pushed prestige appeal. Florey hoped to catch the wave.

The Kalashnikov 41-proof vodka was going to be produced by a distillery in St. Petersburg, with bottling done in England. Florey had to position the product just right for it all to work. Too much on the military angle would turn off drinkers. Too little and it was just another vodka. Florey pushed a well-honed message: “Kalashnikov stands for Russian design, integrity in so far as the product is true to itself, comradeship and strength of character, which epitomizes the General’s life and the role he has played in Russian culture.”

The company’s public offering went well with investors—it was oversubscribed—and listed on the United Kingdom’s JPJL market, a junior market to the OFEX, the country’s independent market focused on small and medium firms.

Florey’s approach was spot-on. Having Kalashnikov as your pitchman guaranteed that the story would be picked up by the world’s major media. By the summer of 2004, Kalashnikov, clad in his honorary general’s uniform complete with colorful ribbons, graced the pages of magazines and newspapers worldwide. Instead of holding an AK across his chest with his traditional two-handed grip, Kalashnikov delicately raised a martini glass up to the camera in a mock toast. This was a brilliant promotional trick; even though vodka was usually served in regular glasses, the martini glass’s unique triangular shape was instantly recognizable as a cocktail drink, whereas a normal cylindrical glass could have contained any ordinary liquid. There was no doubt that the AK-47’s inventor was enjoying a shot of liquor.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «AK-47»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «AK-47» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «AK-47» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.