November 3rd, 1915, ‘Alex to Nicky’:

…One thing Our Friend said, that if people offer great sums (so as to get a decoration ), now one must accept, as money is needed and one helps them doing good by giving in to their weaknesses, and 1000 profit by it – it’s true, but again against all moral feelings. But in time of war all becomes different. 28

Weighed down by so much responsibility and so little power, the Tsar sank into an intermittent mild depression. His apathy was often remarked upon. When he was not doing what his wife told him to, he was said to exist in a kind of torpor. People said he was drunk or drugged, probably by Badmaëv (see chapter 5) – but given the common reliance on opiates in those years, he was probably getting whatever he wanted from the family medical advisor Dr Botkin.

He had no trusted, supportive friends at all. He took the Tsarevich to Moghilev for company. He told the Tsarina that he didn’t want the boy to be over protected and fearful of grown-up life, as he had been. The little boy, who was twelve, and delicate, and always got his own way, was allowed to wear a specially made Cossack uniform. They were happy there, away from the women and the dark forces that enveloped the court.

Not a single important event at the front was decided without a preliminary conference with the starets. From Tsarskoye Selo instructions were given to General Headquarters [the Stavka] on the direct telephone line. The Empress insisted on being kept fully informed by the Emperor on the military and political situation. On receiving this information, sometimes secret and of the utmost importance, she would send for Rasputin, and confer with him. 1

How on earth had he done it? The Tsarina taking advice from a peasant ? To the aristocrats of imperial Russia, it was as if she was taking advice from a chimpanzee.

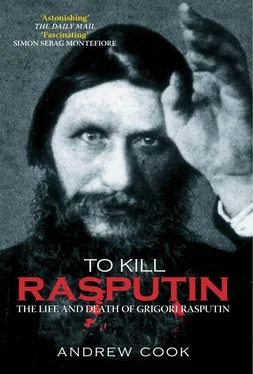

For several years before his death, any outright reference to ‘Our Friend’, as the Tsarina called Rasputin, in the public press was forbidden; the generally understood code in subversive articles was ‘dark forces’. This only served to increase his mystique. When people happened to see him they stared, fascinated. Meriel Buchanan, the Ambassador’s young daughter, spotted Rasputin in April 1916 as she waited to cross a busy Petrograd street. Along bowled an isvostchik with bright green reins, drawn by a shaggy white horse, carrying Rasputin –

a tall black-bearded man with a fur cap drawn down over long straggling hair, a bright blue blouse and long high-boots showing under his fur-trimmed overcoat. 2

She was describing, perhaps unconsciously, the costume he died in. Like everyone else, she mentioned his unusually pale, deep-set, staring eyes. She was not a careless writer, but about Rasputin she used the words ‘compelling’ and ‘repellent’ on the same page, which is significant in itself. His sexual attractiveness increased the more demonised he became.

Sir Paul Dukes, then a music student in Petrograd, shared a flat with Gibbes, the Tsarevich’s English tutor, who told him that, if he cared to, he could see Rasputin on the station platform bound for Tsarskoye on a certain day (Rasputin was usually guarded, but on this day apparently wasn’t). Dukes went along out of curiosity, and was not impressed by the man’s scruffy appearance and ‘rat-like’ eyes. A girlfriend of his had once shared a carriage with Rasputin, only to be lunged at mid-journey; she slapped his face and got out. The same thing had happened to her cousin.

Rasputin was born some 1,600 miles from what was then called St Petersburg, in the village of Pokrovskoe in western Siberia. The village was made up of several streets of spacious one-or two-storey wooden houses, with framed windows and carved, painted beams. It was very much an ordinary village, more prosperous perhaps and more lively than most since it was on both the road and the river. In 1915, the Petrograd newspaper Novoe Vremya , in an anti-Rasputin article, described Pokrovskoe as a poor village, a wretched foggy place, remote and wild, inhabited by Siberian zhigani or rogues. 3

Grigori Rasputin was the second son of Anna Egorovna and Efim Aklovlevich Rasputin, a carter and farmer. Maria Rasputina gave her father’s date of birth as 23 January 1871. 4By the pre-revolutionary Julian calendar, this date corresponds to 10 January. Rasputin’s exact date of birth has been an unresolved issue for over a century. Rasputin biographers have given a variety of dates ranging from the late 1860s through to the 1870s. 5

During Soviet times, encyclopedias and reference books gave Rasputin’s date of birth as 1864/65. Contrary to the generally accepted view that no authoritative contemporary evidence of his birth exists, the answer is to be found in the Tyumen Archives.

According to a Pokrovskoe church register entry, Rasputin’s parents (his father was aged twenty and his mother twenty-two) were married on 21 January 1862. 6Birth registers indicate that between 1862 and 1867 six daughters were born, but all died in infancy. 7Eventually, on 7 August 1867, a son, Andrei, was born. 8The registers from 1869 have regrettably not survived. Before 1869 there is no mention of Grigori Rasputin’s birth in any of the registers. It can therefore be concluded that he could not have been born before 1869. However, this does not imply that it is impossible to establish Rasputin’s exact date of birth. A census of the population of the village of Pokrovskoe, also in the Tyumen Archive, 9contains the name Grigori Rasputin. In the column opposite his name is his date of birth – 10 January 1869, which happens to be St Grigori’s Day. This corresponds to the date given by Maria Rasputina, although she places the year as 1871 not 1869. 10

Rasputin himself was also responsible for the variety of dates given as his date of birth. In a 1907 ecclesiastical file on an investigation into his religious activities, 11Rasputin declares that he is forty-two years of age, therefore implying that he was born in 1865. In a 1914 file on the investigation into an attempt on his life by Khiona Gusyeva, he declares, ‘My name is Grigori Efimovich Rasputin-Novy, fifty years old’, 12which implies 1864 as his year of birth. In the 1911 notebook belonging to Tsarina Alexandra, 13she recorded Rasputin as saying, ‘I have lived fifty years and am beginning my sixth decade.’This suggests he was born in 1861!

Reporters covering the murder of Rasputin at the time stated his age as being fifty. When, six months later, the new Provisional Government set up an Extraordinary Commission of Inquiry to examine Rasputin’s activities, evidence from witnesses who had known him in Siberia and elsewhere was collected by its chief investigator, E.P. Stimson, a respected lawyer from Kharkov. Stimson concluded that Rasputin was born in either ‘1864 or 1865’. 14Tsarina Alexandra referred to him as ‘elder’. He was in fact younger than the Tsar, and it was, perhaps, for this reason that he sought to inflate his age.

According to contemporary accounts, 15Rasputin’s father Efim was comparatively well-off in terms of Pokrovskoe peasants, who in turn had a better standard of living than the peasants in European Russia, who lived in chimneyless log huts. Efim’s single-storey cabin had four rooms – unlike many peasants, who used stretched animal bladders to cover their windows, Efim could afford glass. In later years, Rasputin proudly recalled that as a child he ate white bread rather than the brown bread suffered by peasants in European Russia – and fish and cabbage soup. 16

Rasputin’s mother related that the young Grigori often ‘stared at the sky’ and at first she feared for his sanity. 17Stories abound about his developing powers as a youth – he seems to have had a way with animals and became a horse whisperer. Efim Rasputin had a favourite story 18of how his son’s gift first showed itself. Efim mentioned at a family meal that one of his horses had gone lame that day and could have pulled a hamstring. Grigori got up from the table and went out to the stable. Efim followed and saw Grigori place his hand on the animal’s hamstring. Efim then led the horse out into the yard – its lameness had apparently gone. According to his daughter Maria, Rasputin became a kind of ‘spiritual veterinarian’, 19talking to sick cattle and horses, curing them with a few whispered words and a comforting hand.

Читать дальше