Part I, “The Players,” introduces the four protagonists: Khrushchev, Kennedy, Ulbricht, and Adenauer, whose connecting tissue throughout the year is Berlin and the central role the city plays in their ambitions and fears. The early chapters capture their competing motivations and the events that set the stage for the drama that follows. On his first morning in the Lincoln Bedroom, Kennedy wakes up to Khrushchev’s unilateral release of captured airmen from a U.S. spy plane, and from that point forward the plot is driven by the two leaders’ jockeying and miscommunication. Meanwhile, Ulbricht works behind the scenes to force Khrushchev to crack down in Berlin, and Adenauer navigates life with a new U.S. president whom he mistrusts.

In Part II, “The Gathering Storm,” Kennedy reels from the botched U.S. effort to overthrow Castro at the Bay of Pigs and sees an opportunity to recover his endangered foreign policy standing through an arms buildup and a summit meeting with Khrushchev. The greatly increased refugee exodus from East Germany sharpens the crisis for Ulbricht, who intensifies his scheming to close the Berlin border. Ever mercurial, Khrushchev transforms himself from courting to undermining Kennedy at the Vienna Summit, where he tables a new, threatening Berlin ultimatum and expresses mock sympathy about his adversary’s demonstrated weakness. Kennedy is left disheartened by his own poor performance and grows preoccupied with finding ways to ensure that Khrushchev doesn’t endanger the world by miscalculating American resolve.

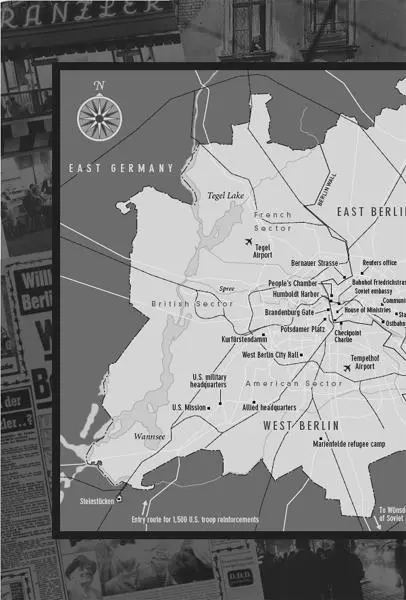

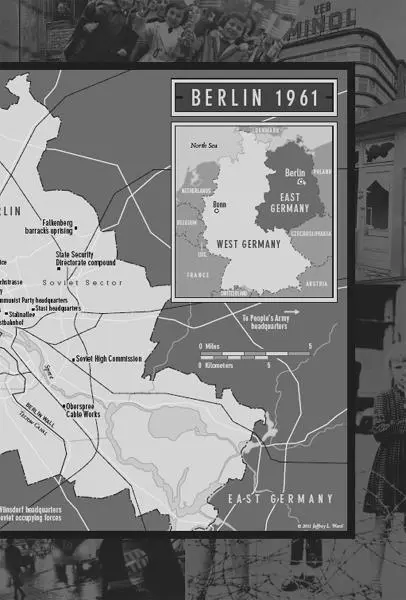

“The Showdown,” the book’s third and final part, documents and describes the dithering in Washington and the decisions in Moscow that result in the stunning nighttime August 13 border-closure operation and its dramatic aftermath. Privately, Kennedy is relieved by the Soviet action and hopes that the Soviets will become easier partners with the East German refugee matter solved. He quickly learns, however, that he has overestimated the potential benefits of a Berlin Wall. Dozens of Berliners engage in desperate escape attempts, some with deadly outcomes. Internationally, the crisis intensifies as Washington debates how best to fight and win a nuclear war, Moscow wheels its tanks into place, and the world holds its breath—just as it would again a year later when the ripples of Berlin 1961 would result in the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Sprinkled throughout the narrative are vignettes of Berliners themselves, who are buffeted by their involuntary role in a decisive moment of Cold War history: the survivor of multiple Soviet rapes who tries to tell her story to a people who just want to forget; the farmer whose resistance to land collectivization lands him in prison; the engineer whose flight to the West ends with her victory at the Miss Universe pageant; the East German soldier whose leap to freedom over coils of barbed wire, with his arm releasing his rifle in mid-flight, becomes the iconic image of liberation; and the tailor who is gunned down while trying to swim to freedom, the first victim of East German shoot-to-kill orders for would-be escapees.

Early in 1961, it was just as unthinkable that a political system would put up a wall to contain its people as it was inconceivable twenty-eight years later that the same barrier would crumble peacefully and seemingly overnight.

It is only by returning to the year that produced the Berlin Wall and revisiting the forces and the people surrounding it that one can properly understand what happened and try to settle a few of history’s great unanswered questions.

Should history consider the Berlin Wall’s construction the positive outcome of Kennedy’s unflappable leadership—a successful means of avoiding war—or was the Wall instead the unhappy result of his missing backbone? Was Kennedy caught by surprise by the Berlin border closure, or did he anticipate it and perhaps even desire it because he believed it would defuse tensions that might lead to nuclear conflict? Were Kennedy’s motivations enlightened and oriented toward peace, or cynical and shortsighted at a time when another course of action might have spared tens of millions of Eastern Europeans from another generation of Soviet occupation and oppression?

Was Khrushchev a true reformer whose efforts to reach out to Kennedy following his election were a genuine effort (that the U.S. failed to recognize) to reduce tensions? Or was he an erratic leader with whom the U.S. could never have done business? Would Khrushchev have backed off from the plan to build a Berlin Wall if he had believed Kennedy would resist? Or was the danger of East German implosion so great that he would have risked war, if necessary, to shut off the refugee flow?

The pages that follow are an attempt to shed new light, based on new evidence and fresh insights, on one of the most dramatic years of the second half of the twentieth century—even while we try to apply its lessons to the turbulent early years of the twenty-first.

1

KHRUSHCHEV: COMMUNIST IN A HURRY

We have thirty nuclear weapons earmarked for France, more than enough to destroy that country. We are reserving fifty each for West Germany and Britain.

Premier Khrushchev to U.S. Ambassador Llewellyn E. Thompson Jr., January 1, 1960

No matter how good the old year has been, the New Year will be better still…. I think no one will reproach me if I say that we attach great importance to improving our relations with the USA…. We hope that the new U.S. president will be like a fresh wind blowing away the stale air between the USA and the USSR.

One year later, Khrushchev’s New Year’s toast, January 1, 1961

THE KREMLIN, MOSCOW

NEW YEAR’S EVE, DECEMBER 31, 1960

It was just minutes before midnight, and Nikita Khrushchev had reason to be relieved that 1960 was nearly over. He had even greater cause for concern about the year ahead as he surveyed his two thousand New Year’s guests under the towering, vaulted ceiling of St. George’s Hall at the Kremlin. As the storm outside deposited a thick layer of snow on Red Square and the mausoleum containing his embalmed predecessors, Lenin and Stalin, Khrushchev recognized that Soviet standing in the world, his place in history, and—more to the point—his political survival could depend on how he managed his own blizzard of challenges.

At home, Khrushchev was suffering his second straight failed harvest. Just two years earlier and with considerable flourish, he had launched a crash program to overtake U.S. living standards by 1970, but he wasn’t even meeting his people’s basic needs. On an inspection tour of the country, he had seen shortages almost everywhere of housing, butter, meat, milk, and eggs. His advisers were telling him the chances of a workers’ revolt were growing, not unlike the one in Hungary that he had been forced to crush with Soviet tanks in 1956.

Abroad, Khrushchev’s foreign policy of peaceful coexistence with the West, a controversial break with Stalin’s notion of inevitable confrontation, had crash-landed when a Soviet rocket brought down an American Lockheed U-2 spy plane the previous May. A few days later, Khrushchev triggered the collapse of the Paris Summit with President Dwight D. Eisenhower and his wartime Allies after failing to win a public U.S. apology for the intrusion into Soviet airspace. Pointing to the incident as evidence of Khrushchev’s leadership failure, Stalinist remnants in the Soviet Communist Party and China’s Mao Tse-tung were sharpening their knives against the Soviet leader in preparation for the 22nd Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Having used just such gatherings himself to purge adversaries, all Khrushchev’s plans for 1961 were designed to head off a catastrophe at that meeting.

Читать дальше