In April 1945 the Japanese authorities cut food rations again for all citizens, including the inhabitants of Hiroshima. The rice ration of three bowls a day had for a long time been routinely mixed with soya, but rice was henceforth provided on only twenty days out of any month. However, one resident recalled that the continued availability of tea was consoling, providing “comfort and a reminder of the rituals of prewar life.” That same month, the evacuation of some of Hiroshima’s schoolchildren began. They were sent to rural temples and assembly halls. Older pupils of no more than sixteen or eighteen years of age supervised those who were left in order to free teachers for war work. They were given the briefest of training and instructed not to use the same toilets as their pupils since, as “higher beings,” they should not be seen by them to perform basic bodily functions. They were also told that in the event of an attack “their first priority, even before the safety of the pupils, should be to protect the portraits of the emperor and empress” that hung in every classroom.

Hiroshima had still not, however, been attacked. Inhabitants speculated about why the much-feared “B-San” or “Mr. B.”—as the B-29 Super Fortress bombers were known—had not visited their city as they had so many others. In earlier years lack of viable agricultural land had forced many people from the area around Hiroshima to emigrate to Hawaii and California. As a consequence, some Hiroshima residents accepted as true the comforting speculation that President Roosevelt had agreed to spare Hiroshima from attack in response to petitions from Japanese Americans, many of whom still had relatives in Hiroshima. Others thought that the city was being saved to serve as U.S. headquarters when the Americans conquered Japan. Such defeatism was becoming more common, so the secret police, the Kempei-Tei, based in Hiroshima castle, began a roundup of dissidents and defeatists in early May. Among the more than three hundred people swiftly detained in Hiroshima was the diplomat Shigeru Yoshida, later to become prime minister of Japan.

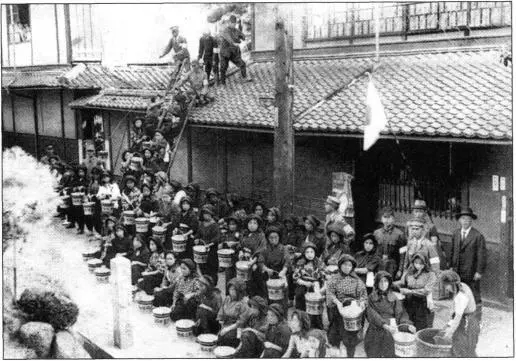

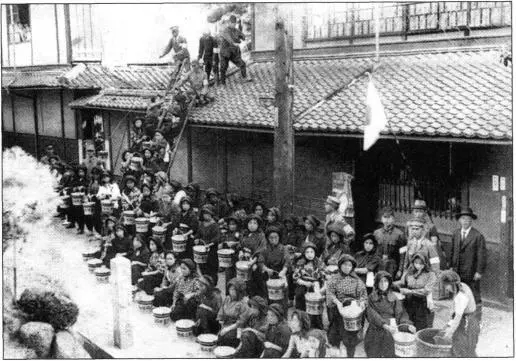

Fire drill to prepare for air raids

A few weeks before, Hiroshima had welcomed a new arrival: Field Marshal Shunroku Hata. The sixty-five-year-old veteran of the wars in China had been given the task of defending Japan against invasion and chose to make the city his base, establishing the Second General Army Headquarters there. He immediately gave orders for further military drills for all ages and both sexes.

Scarce fuel was set aside so that children could make Molotov cocktails to be stockpiled for use against the invaders. Even the infirm and wheelchair-bound were put to work making booby traps to protect the beaches. The many Koreans transported from their homeland to undertake forced labor in Hiroshima’s factories were compelled to work longer hours despite reduced rations. In the dockyards the Japanese began assembling suicide craft to defend Hiroshima Bay. They packed small boats with explosives and a motor sufficiently powerful to speed them on a one-way mission to explode against the invaders’ landing craft. Suicide divers, known as Fukuryus or “crouching dragons,” were trained to swim out to sea to attach limpet mines to ships. Experiments were made with concrete shelters in which squads of Fukuryus could lie concealed offshore for ten hours before rising to attack the incoming landing craft. Each day, the newspapers, all of which were state-controlled and strictly censored, urged their readers to give thanks for imperial benevolence and to be ready to die for Hirohito. Many of those in Hiroshima would have little choice in the latter.

TWENTY-ONE

“GERMANY HAD NO ATOMIC BOMB”

IN JANUARY 1945 Walther Gerlach, the newly appointed German plenipotentiary of fission research, ordered Heisenberg and all remaining scientists to flee Berlin immediately. Otto Hahn had left a few weeks earlier. During 1944 Allied bombs had destroyed a wing of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry and reduced his office to rubble. (Among the possessions he most regretted losing were letters from Ernest Rutherford.) He decided to send his team and whatever he could salvage to the small town of Tailfingen in southwest Germany, not far from Heisenberg’s evacuated team under Max von Laue at Hechingen. He arrived there himself in late 1944.

Hahn watched uneasily as Allied bomber squadrons passed overhead, but no bombs fell on Tailfingen. In early 1945 he found himself in greater danger from the local Gestapo for trying to shield Frau von Traubenberg, the Jewish physicist wife of one of his team, when, after her husband died suddenly of a stroke, she was arrested. Hahn argued that the woman was vital to what he called “our secret work on uranium” but failed to secure her release. However, she was sent to the Theresienstadt holding camp, where she was given a small room in which to work, and survived the war. Hahn himself was by now under increasing surveillance from the Nazi authorities, to whom he had been denounced as hostile to the Third Reich and who subjected him to harsh interrogations.

Kurt Diebner had dispatched some members of his small, army-sponsored reactor project in Berlin to greater safety, choosing Stadtilm, near Weimar. Yet, like Heisenberg, he had chosen to remain in Berlin to continue working on his reactor model. Neither of their programs had yet yielded significant results and certainly no chain reaction. Paradoxically, Diebner, with the least resources, had made the most progress. The rivals had been experimenting with different configurations of uranium to see which produced more neutrons. Diebner’s trials using cubes of natural uranium suspended on wires in heavy water had generated more neutrons than Heisenberg’s use of uranium plates. However, still in Berlin with his reactor team, Heisenberg clung stubbornly to his preferred plate design until, admitting defeat at last in late 1944, he ordered the plates to be remade into cubes. But in January 1945, just as he and his team had finished attaching hundreds of cubes of uranium to aluminum wires and submerging them in heavy water, came Gerlach’s order to leave. The next day, Diebner also departed, fleeing in a convoy of trucks containing both his own and Heisenberg’s equipment.

Despite bombs and the strafing of low-flying Allied fighter planes, Heisenberg reached Hechingen safely, where he lodged directly opposite a house that had once belonged to Einstein’s uncle. He was not, however, reunited with his uranium and heavy water until the end of February due to a squabble with Diebner, who had tried to appropriate them for his own experiments at Stadtilm. Heisenberg spent the last weeks of the war reassembling his reactor in a wine cellar cut deep into rocks in the village of Haigerloch near Hechingen. He was joined by von Weizsacker, who, as the Allies advanced, fled from the French city of Strasbourg, where since 1942 he had held the physics chair of a new university set up by the occupying Nazis. In their cave Heisenberg and von Weizsacker managed to generate more neutrons than ever before but, in these desperate, dying days of the war, could still not make their reactor go critical.

• • •

Unaware of the small scale and technical failures of the German fission program, General Groves had long feared that “the Germans would prepare an impenetrable radioactive defense against our landing troops.” In late November 1943 he had argued forcefully for a scientific intelligence-gathering unit to be set up and, as usual, got his way. The mission itself, without Groves’s prior knowledge, acquired the name “Alsos”—ancient Greek for grove. No one was quite sure how.

Читать дальше