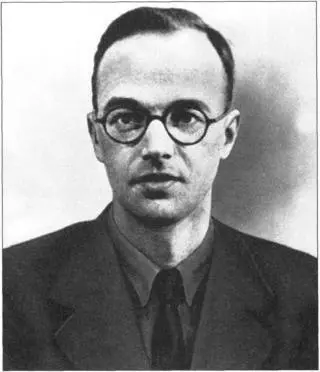

Klaus Fuchs

On first arriving in the United States with the British mission, Fuchs had spent nine months in New York working on the theory of gaseous diffusion. During evening meetings, usually in Manhattan though sometimes in Brooklyn or Queens, he gave his handler “Raymond”—the alias of the Soviet agent Harry Gold—information about it. At first Fuchs just talked. Then he began handing over notes, which, like everything he gave to Gold, he had written himself. Fuchs’s information convinced Kurchatov to concentrate on gaseous diffusion for separating uranium.

Fuchs’s transfer to Los Alamos in August 1944—especially his assignment to work on implosion and plutonium—was a major breakthrough for the Soviets. For the first time, Fuchs saw the scale of the American program and understood the importance of plutonium as an alternative fuel to U-235. Somehow, the earnest young scientist, always ready to run errands for others in the beaten-up Buick he had loaned Richard Feynman, became a familiar figure around the site whose movements, despite tight security, went unremarked. In February 1945 he passed Harry Gold a detailed report on the design of the plutonium bomb. It described the problems with spontaneous fission that had led the Los Alamos teams to develop implosion. Fuchs also explained that far less plutonium than uranium was needed to make a bomb—only eleven to thirty-three pounds.

In subsequent months, Fuchs handed over further details, including a sketch of the bomb. His reports, in conjunction with details about high-explosive lenses supplied by the machinist David Greenglass, who was busily casting the explosives to be used in the lenses, were welcomed in Moscow as “extremely excellent and very valuable.” They convinced Kurchatov to recommend to Stalin that the Russians too should pursue an implosion plutonium bomb. Fuchs also told Gold that if the testing of the plutonium bomb was successful, there were plans to drop it on Japan.

• • •

Japan’s own nuclear program was struggling. Yoshio Nishina had reported to the Imperial Navy the scientists’ conclusions that although an atomic bomb was feasible, it might take ten years to build and would require immense resources. After a series of meetings culminating in March 1943, about which the naval representative reported that the more the scientists debated the issue, “the more pessimistic became the atmosphere,” the navy, unsurprisingly, lost interest. Instead, they asked the scientists to focus on shorter-term projects such as radar.

However, just as the navy had taken the lead when the army’s commitment to nuclear research had waned, so, in May 1943, the army intervened to fill the nuclear vacuum. It decided to subsidize what it called the “N-Project,” in tribute to Nishina, and left it to him to decide how best to direct his research. He decided to focus the work of his group at Tokyo University on the separation of the fissile U-235 from U-238 by the use of thermal diffusion. However, he made slow progress, and it was only with great difficulty that his group manufactured small quantities of uranium hexafluoride gas. In July 1944 they made their first attempts at isotope separation using a thermal diffusion column, wherein they hoped the effect of heat would separate the U-238 in the hexafluoride gas from the U-238. The lighter U-235 would rise to the top of the column, and the heavier U-238 would fall to the bottom. Yet however hard they tried and whatever modifications they made, Nishina and his team could not get the apparatus to work.

Japan’s military situation had also not prospered. Two years earlier, on £ June 1942, it had suffered its first major reverse when an attack by a large Japanese carrier task force on Midway Island, a stepping-stone to the planned conquest of Hawaii, was beaten back by American naval airpower. Japan lost 332 aircraft and four aircraft carriers, three of which had taken part in the attack on Pearl Harbor. Although the United States had also suffered losses, its industrial power had allowed it to replace them much more easily than Japan. Japanese expansion had reached its high-water mark, and slowly the Allies began to push back its armies in the Pacific, in New Guinea, and on the frontiers of India. In April 1943 the naval commander in chief, Isoroku Yamamoto, had died when the aircraft on which he was traveling on an inspection visit was shot down in the South Pacific by an American fighter as a result of an intercepted and decoded message.

In July 1944, U.S. marines took Saipan. Thirty thousand Japanese troops and fifteen thousand Japanese civilians died, many by their own hands to avoid capture. Tinian fell quickly thereafter. Saipan was the first piece of what had been Japanese territory before the war to be lost. The Japanese did not admit the loss until twelve days later when they praised the garrison, which had “fought victoriously to the last man.” Tokyo Radio then continued, on behalf of the government, “The American occupation of Saipan brings Japan within the range of American bombers but we have made the necessary preparations.”

That summer, the cinemas began to show a newsreel entitled The Divine Wind Special Attack Forces Take Off, glorifying the first kamikaze pilots as, before their one-way missions, the young suicide bombers vowed fealty to their emperor and, smiling, climbed into their cockpits. The “divine wind,” or “kamikaze,” was a reference to the winds said to have been sent by the deities to protect their favored country, Japan, at critical times in its history. In particular, in 1281 the “divine wind” had destroyed an invading Mongol fleet.

In Hiroshima, neighborhood associations began to organize air-raid drills and to give guidance on rallying areas in the case of attack. The associations distributed little brown-and-white pottery cups with bracing inscriptions such as “Neighborhoods unite and resist.” Those whom neighborhood leaders observed or overheard engaging in defeatist talk or activity were reported to the feared secret police—the Kempei-Tei, based in Hiroshima castle. Schoolchildren of thirteen years and older had already been conscripted to work for up to eight hours a day in weapons factories. Now, in their spare time, they were ordered to dig trench shelters in hillsides surrounding the city as protection against the bombers. Everyone, young and old, male and female, had to drill with bamboo spears.

The Japanese Steel Products Group organized a conference in Hiroshima to encourage increased productivity to retaliate against the Anglo-Americans. “The beasts are desperate, we must strike back,” the workers were warned. However, lack of the very raw materials, such as oil and iron ore, that the Japanese had gone to war to obtain meant that there were no longer private cars or taxis, only trams or bicycles. There were few trucks and much less shipping in the harbor. Nearly 80 percent of the Japanese merchant fleet had been lost, as had nearly 50 percent of Japanese naval tonnage. Lack of steel meant that replacements for the merchantmen were being made of wood. Lack of fuel meant that pilots received less training and that the coastal patrol boats were almost invariably in Hiroshima Harbor rather than at sea. Lack of fuel, coupled with American attacks on the few fishing trawlers that did find enough to sail, also meant that fish—a staple of the Japanese diet—was becoming scarcer.

Fish, like other food, was tightly rationed and “canned” in patent earthern-ware jars to save metal. In a single week the ration for a family might be a cake of bean curd, one sardine or small mackerel, two Chinese cabbages, five carrots, four eggplants, half a pumpkin, and a little rice. Most meals consisted mainly of watery soup with a few vegetable shreds. The citizens grew and collected what extra food they could. Schoolchildren, digging the shelters on the hills, brought back the excavated earth, which they laid in layers on flat roofs or piled in old containers to grow vegetables such as sweet yams. Bramble shoots were stripped of their prickles and chewed. Reeds from the city’s rivers were boiled and eaten. Anyone who had the opportunity to leave the city took a heavy stick with them so that they could hunt down the few remaining wild rabbits. Their meat was a tasty supplement to the diet, and their fur was collected by the neighborhood associations for use in lining pilots’ flying jackets. When the rabbits were gone, worms, grubs, and insects were spitted and barbecued over such small fires as the shortages of coal and coke allowed.

Читать дальше