A fresh insight into the politics of this period is offered in Carson, Richard III. For Richard’s genuine fear of witchcraft see John Leland, ‘Witchcraft and the Woodvilles: A Standard Medieval Smear?’ in Reputation and Representation in Fifteenth-Century Europe, ed. Douglas Biggs, Sharon Michalove and Albert Compton Reeves (Leiden, 2004); for his reaction to the sexual immorality of Edward IV’s court: David Santiuste, ‘“Puttyng Downe and Rebuking of Vices”: Richard III and the Proclamation for the Reform of Morals’, in Medieval Sexuality: A Casebook, ed. April Harper and Caroline Proctor (London, 2008). Cecily Neville’s well-deserved reputation for piety in her later life does not preclude the possibility of an indiscretion in her youth. The issue of an adultery hearing is echoed in the one book of Cecily’s she dispensed with before her death: Mary Dzon, ‘Cecily Neville and the Apocryphal Infantia Salvatoris in the Middle Ages’, Medieval Studies, 71 (2009); and for the papal indulgence found in her coffin: Sofija Matich and Jennifer Alexander, ‘Creating and Recreating the Yorkist Tombs in Fotheringhay Church (Northamptonshire)’, Church Monuments, XXVI (2011).

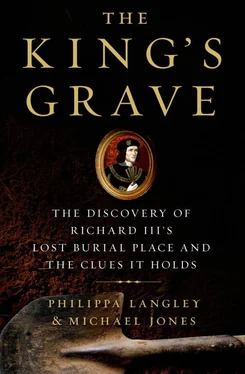

Chapter 7: The Discovery of the Skeletal Remains

At the time of writing, the unidentified female remains discovered in the charnel in Trench Three would, after investigation, be reinterred in a nearby church in Leicester. For the physical description of Richard see Chapter 8. Information on the former grammar school building in Leicester from Leon Hunt, Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment for Land at Greyfriars, St Martin s (NGR: SK 585 043), ULAS, 12 April 2013, commissioned by Philippa Langley for the Looking for Richard project. The 10,000-square-foot neo-gothic building was built as Alderman Newton’s School in 1864 and extended in 1887 and 1897. In 1979 the buildings became Leicester Grammar School. See also I.A.W. Place, The History of Alderman Newton’s Boys School, 1836–1914, University of Leicester (1960). In December 2012 Leicester City Council announced its purchase of the former grammar school for £850,000: Leicester Mercury, Monday, 3 December 2012. It seems that the sarcophagus found in Trench Three had been located on the Ground Penetrating Radar Survey. Its shape is clearly marked in the central area of the former grammar school car park: Robbie Austrums, Geophysical Survey Report, Greyfriars Church, Leicester, for Philippa Langley, Stratascan, September 2011. On 1 April 2013 it was announced that a four-week dig would take place at the Greyfriars site, Leicester in July 2013. The dig will now be part of the city council’s continuing work on the new Richard III Visitor Centre that is due to open in spring 2014 in the former grammar school building. The work is to be undertaken by Richard Buckley and the team at ULAS who hope to uncover much more about the Greyfriars Church and its buildings.

Chapter 8: Richard as King

For Richard, Howard and Berkeley see Hicks, The Prince in the Tower. On the coronation: Sutton and Hammond, Coronation of Richard III. The witness list is Berkeley Castle Muniments (BCM)/A/5/5/2. On Richard’s kingship see Charles Ross, Richard III; Pollard, Richard III and the Princes in the Tower; Hicks, Richard III; Horrox, Richard III: A Study in Service. On the fate of the princes I have followed Charles Ross, Richard III and Pollard, Richard III and the Princes in the Tower. For more recent sources see John Ashdown-Hill, ‘The Death of Edward V – New Evidence from Colchester’, Essex Archaeology and History, 35 (2004), and Nigel Saul, The Three Richards (London, 2006), citing Bodleian Ashmole 1448, a source written in the immediate aftermath of Bosworth, with Henry Tudor still referred to as ‘earl of Richmond’: ‘Richard… removed them from the light of the world… vilely and murderously.’ Some believed they had already been killed before Richard took the throne; others, shortly afterwards: Philip Morgan, ‘The Death of Edward V and the Rebellion of 1483’, Historical Research, 68 (1995). On the legal rights of Elizabeth of York’s three surviving younger sisters in the Tudor period, which inhibited Henry VII from thoroughly investigating the princes’ survival, see T.B. Pugh, ‘Henry VII and the English Nobility’, in The Tudor Nobility, ed. George Barnard (Manchester, 1992).

On Richard’s increasing identification with his father: Shropshire Record Office, 3365/67/60, a memorandum of the king’s instructions for setting up a perpetual chantry at Wem (10 September 1484). Ashdown-Hill, Last Days of Richard III, is valuable on Richard’s marriage negotiations with the House of Portugal. Richard’s gathering of artillery is from Ross, Richard III; information on the Milanese armour has kindly been provided by Tobias Capwell.

Chapter 9: The Identification of the Remains

Mathematics students at the University of Leicester calculated that the archaeologists had a less than 1 per cent chance of finding the grave, with chances of discovery on the very first day at just 0.0554 per cent, or odds of 1,785 to 1 against: University of Leicester, Press Office, 11 March 2013. The dental analysis was of particular interest as we have the dental record of some of Richard’s relations: Anne Mowbray, Eleanor Talbot and the bones in the urn in Westminster Abbey, reputed to be those of Richard’s nephews, the Princes in the Tower. Later, I approached other scoliosis specialists who confirmed that severe scoliosis, particularly in later life, is painful. And the Scoliosis Association in the UK confirmed that the word ‘hunchback’ is very distressing and no longer used. The skeleton is missing the left fibula (lower leg bone). Apart from a few small hand bones (twelve missing out of a total of fifty-four, which is a good recovery rate), the feet and a few teeth, the remains were complete: University of Leicester, March 2013.

A rondel dagger is a modern term for a type of dagger with a circular, round cross-guard towards the blade, which could be single or multi-edged, and often a pommel of similar form. The rondel dagger was used by knights between the fourteenth and early sixteenth centuries and was so named because of the distinctive shape of its grip. After this examination of the bones, a third wound on the face was discovered: a tiny nick in the mandible also on the right and an inch or so above the other, making a total of nine identified wounds on the skull, with the possibility of more to be confirmed. At the time of writing it was unclear whether this new wound could support the theory that King Richard’s helmet was cut off him. The lack of trauma to the face further strengthened my conviction that Henry Tudor did not leave Richard’s body on the battlefield as it was his prize. At the time of writing, Jo Appleby confirmed that the soil analysis beneath the body for parasitic sample, the isotopic report and the dental analysis are not yet available, but should be included in the archaeological report some time towards the end of 2013.

The facial reconstruction process has been blind-tested at the University of Dundee using living people, CT scans and photography, and the accuracy tested using recognition levels and anthropometry (scientific study of the measurements and proportions of the human body). The second living relative of Richard III who gave a sample of their DNA for the tests wishes to remain anonymous.

An excellent survey on the sources is provided in Bennett, Battle of Bosworth. For a recent archival discovery about the battle see John Alban, ‘The Will of Thomas Longe of Ashwellthorpe, 1485. A Yorkist Soldier at Bosworth’, Ricardian XXII (2012). For Nottingham’s intelligence gathering before and during Bosworth, see Penelope Lawton, ‘Riding Forth to Aspye for the Town’, Ricardian Bulletin (September 2012). My ideas on Richard’s personal duel with Henry Tudor owe much to conversations with Cliff Davies and are also developed in Michael Jones, ‘The Myth of 1485: Did France Really Put Henry Tudor on the Throne?’, in The English Experience in France 1450–1558: War, Diplomacy and Cultural Exchange, ed. David Grummitt (Aldershot, 2002). The French mercenary’s account, written at Leicester on 23 August 1485, is from Jones, Bosworth 1485, and my views on the battle have been modified by the important archaeological finds summarized in Glenn Foard, ‘Bosworth Uncovered’, in BBC History Magazine, 11 (2010).

Читать дальше