Many who had done less dangerous labor, like Nimenko, saw these bio-robots as political kin. Unlike Kulyk, Nimenko remained physically and socially mobile. For him, science had social utility. It could be called upon to set a price on survival, to create assets based on that survival, assets that could be used to leverage the state for compensation. Nimenko had mastered a language of symptoms and science. He was also part of a disabled persons fund that mediated the claims of other cleanup workers. He was scientifically literate and had a strong sense of the value of science in empowering him to set the value of his life. He knew how to read cytogenetic tests indicating chromosomal aberrations in his cells. He used the ambiguities of radiation science—and there are many—to facilitate his chances of having his case reassessed favorably for his compensation claim. Referring to a request he had made in 1991 for a retrospective quantification of his internal dose, Nimenko told me:

The central polyclinic of our ministry arranged a contract with the Institute of Oncology of the Ukrainian Academy of Medical Sciences. I went to the director of the polyclinic and said I want to know my dose burden. After three months, they gave me a dose burden based on the increase of the level of chromosomal aberrations in my blood, which testifies that radiation activity in my organism is higher than 25 rem…. That was five years after the accident. And if you throw away five more years, how much dose I received, I don’t know . Obviously it was more. Nonetheless there is radiation in my body.

Where ignorance once amounted to a form of repression (in the Soviet period), it is now used as a resource in the personal art of biosocial inclusion. Nimenko based his self-account on an accumulation of unknowns. In this regard, he used scientific knowledge in a specific way: not to know but to circumscribe what he can never know. Nimenko crafted his social identity in terms of what Hans-Jorg Rheinberger in another context has referred to as a “characteristic irreducible vagueness” (1995:48). He politicized what-he-can-never-know as a means of securing his place as a scientific subject and, by extension, as an object in an official exchange relation with the state. In this move, he acquired a name, a document, and a position as an individual “in the rights he enjoys and his place in the tribe, as in its rites” (Mauss 1985:11).

The Unstoppable Course of Radiation Illness

I went to the state’s Ministry of Statistics to ascertain the impact these developments in the politics of knowledge might have had on health data. To my surprise, beginning in 1990 (the year the laws on Chernobyl social protection were being publicized by Ukrainian legislators), I noticed a sharp increase in the clinical registration of illnesses under the category “symptoms, signs, and ill-defined states”—Class 16 in the International Classification of Diseases. These states include anything from insomnia, fatigue, and persistent headaches to personality changes, hallucinations, and premature senility. In a sense, people were claiming Chernobyl as their ill-defined state.

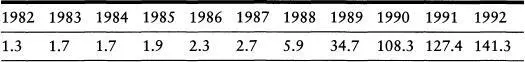

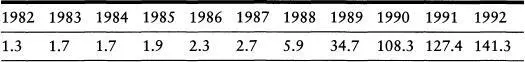

Table 1

Data on “Symptoms, Signs, and Ill-defined States” (per 10,000)

Source: Ministry of Statistics, Kyiv, Ukraine.

International observers, not surprisingly, grew ever more skeptical of claims to a sudden expansion of Chernobyl health effects and strongly criticized Ukrainian scientists for their failure to prove or disprove these claims on the basis of epidemiological criteria of causality. Yet as this book shows, the complex strategies, techniques, and relations that have been engendered within this postsocialist environment are not measurable by scientific criteria of causality alone. Upon these relations of injury and compensation, other risks, particularly those connected with the market transition, are superimposed.

The collective and individual survival strategy called biological citizenship represents a tangle of social institutions and the deep vulnerabilities of persons; it is also part of a broader story of democratizing processes and structures of governance in the postsocialist states. Here the experience of health is irreducible to a set of norms of physiological and mental activity, or to a set of cultural differences. Only through concrete understandings of particular worlds of knowledge, reason, and suffering, and the way they are mediated and shaped by local histories and political economies, can we possibly come to terms with the intricate human dimensions that protect or undermine health. Seen this way, health is a construction as well as a contested way of being and evolving in the world.

Chapter 2

Technical Error: Measures of Life and Risk

Dmytro is a miner from the coal-mining region of Donbas in Ukraine. I met him at the Radiation Research Center where he came to “settle his social matters.” Within ten days following the Chernobyl accident, he was one of two thousand coal miners from his region mobilized to carry out work at the disaster site. Dmytro said he underwent an occupational health screening before his mobilization: “I knew I was healthy before going there.” Dmytro lacked a special protective mask during his month-long work, which involved digging tunnels under the reactor. Miners injected these tunnels with liquid nitrogen and other gases in attempts to cool the reactor core. Dmytro received five times his average salary for this work.

Since his work at Chernobyl, Dmytro has undergone annual hospital examinations and monitoring at the Radiation Research Center. In August 1996, he was admitted to the center’s Division of Nervous Pathologies with cerebral, cardiac, and pulmonary disorders. Dmytro said he had one daughter, born five years before the disaster. He decided not to have any more children because he believed himself to be genetically damaged. “A healthy child cannot come from a sick father,” he reasoned. [1] As a disabled person, Dmytro earned $150/mo. His wife was a civil servant and earned $40/mo. His pension would have been adequate had he not had to spend half of it for medicines. He wanted level two disability, by which he would be officially certified as having lost 80 percent or more of his work capacity. This upgrading would have doubled his pension to $300/mo.

His documents showed him to be categorized as a disabled person (level three). This meant he was officially recognized as having lost 50 percent of his labor capacity. Before entering the center, Dmytro decided to quit his job and secure full disability benefits from the state. He wanted to qualify for higher disability status, a certification that he had lost 80 percent or more of his work capacity. This move would have doubled his pension and allowed him to pay for his medical treatments. Behind his hospital referrals, institutional rubber stamps, dose assessments, diagnoses, corrections to diagnoses, further diagnoses, and other papers conferring his Chernobyl identity was a person who perceived himself to have lost the capacity to father, to work, and to live a normal life. Dmytro complained of emotional stress and gastritis. Like many patients I met at the center, he no longer identified himself as a worker of a state enterprise; he had come to see himself as a “prospective invalid.” This was an interesting word choice since the related Russian words perspektivnyi/neperspektivnyi were vintage statist terms for deciding the fates of financial investment in Soviet towns and villages. He was engaged in an everyday form of life science to increase his chances of becoming worthy of investment. Dmytro knew the level of internal radiation he had received on the basis of a count of aberrations in his chromosomes. He calculated his lost work capacity and amassed diagnoses. He referred to the radiation in his body as a “foreign burden” ( chuzhe hore )—unnatural in origin and creating a new locus where “there is no peace.” He was but one of many left to assess, but without an exact numerical equivalent for, his foreign burden. His narrative also suggests that technical measures used to define the biological effects of Chernobyl were malleable. They acquired different values over time depending on the contexts of their use.

Читать дальше