From the end of July 1943 our tremendous industrial capacity was diverted to the huge missile later known as the V-2…. Hitler wanted to have nine hundred of these produced monthly. The whole notion was absurd. The fleets of enemy bombers in 1944 were dropping an average of three thousand tons of bombs a day over a span of several months. And Hitler wanted to retaliate with thirty rockets that would have carried twenty-four tons of explosives to England daily. That was equivalent to the bomb load of only twelve Flying Fortresses. I not only went along with this decision on Hitler’s part but also supported it. That was probably one of my most serious mistakes.

The argument that the V-2 was unviable because of its cost had, however, been answered by R. V. Jones in his paper, already quoted, circulated in 1944, when only a few missiles had arrived:

The protagonists for the development of very long range rockets would probably have, in Britain at any rate, to meet the criticism that it would not be worth the effort expended. The A-4 has already shown us that our enemies are not restrained by such considerations and have thereby made themselves leaders in a technique which sooner or later will be regarded as one of the masterpieces of human endeavours.

The truth is that in war the normal rules of finance cease to apply. When it comes to weapons, nations can always afford what they want, as Germany, which so many experts had proclaimed bankrupt and unable to sustain a long war, had already amply demonstrated, and as the Allies had shown when shouldering the staggering cost of producing the first atomic bombs. Nor was the suggestion that the V-2 was less cost-effective than the German equivalent of a Mosquito or a Flying Fortress valid, for the reason Cherwell and Speer preferred to ignore: that the rocket always got through, while – as the British bombing offensive confirmed – the defence was more powerful than the offensive in the case of manned aircraft. A V-2 which landed in Stepney or Ilford was infinitely more useful than a bomber which ended, as any German manned bomber was likely to do by 1944, in the Channel. The history of the flying bomb underlined this truth. It had been unbelievably cheap, at £125, a fantastic military bargain, which cost not a single German life, until it became almost as vulnerable to the RAF as the Heinkels and Junkers of the Luftwaffe in its heyday. The rocket was – all moral considerations set aside, as they were by the Germans —a superb weapon, an immense leap forward in warfare, because it was totally unbeatable. As time, experience and further research increased its power and accuracy, it could have become a war-winning one.

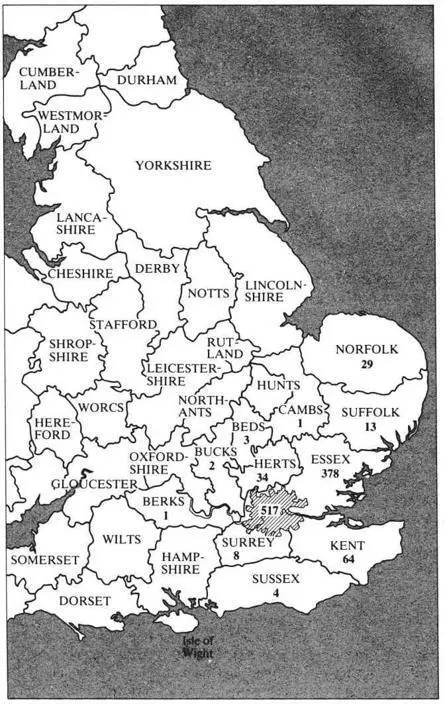

What, then, did the rockets achieve, apart from providing the necessary first step into a new world of military technology? The official British historian, using enemy as well as domestic sources, put the total launched at 1403, of which 288 went astray or exploded en route, 61 landed offshore and 1054 exploded on the mainland, 517 of these in London, 537 in eleven other counties. As mentioned earlier, they killed 2754 people and seriously injured 6523, a total of 9277 major casualties; they did a great deal of militarily significant damage; and they caused a great deal more destruction to other property at a time when the building industry was already badly stretched. In attacking morale, that target which so many champions of air power had proclaimed as even more important than weakening the enemy’s industrial potential, the rocket was incomparably the most effective weapon so far devised: the low ebb to which spirits in southern England sank during that last and, as it seemed, unnecessary winter of the war is evident again and again in the reminiscences of the time. And all this excludes what the V-2s achieved in Belgium, which suffered proportionately far more than England: 1214 V-2s fell in the Antwerp area alone, one of them killing 242 servicemen and 250 civilians in a single direct hit on a cinema, the largest death roll caused by any missile of the whole European war.

‘If we had had this rocket in 1939, we would never have had this war,’ Hitler told Dornberger in 1943, apologizing for his previous lack of faith in the V-2. He may well have been right; sufficient reason by itself – when the horrifying alternative, a Nazi-dominated world, is considered – for giving the rocket its belated due as not merely a masterpiece of scientific and engineering brilliance but as the most formidable and fearful weapon of its time.

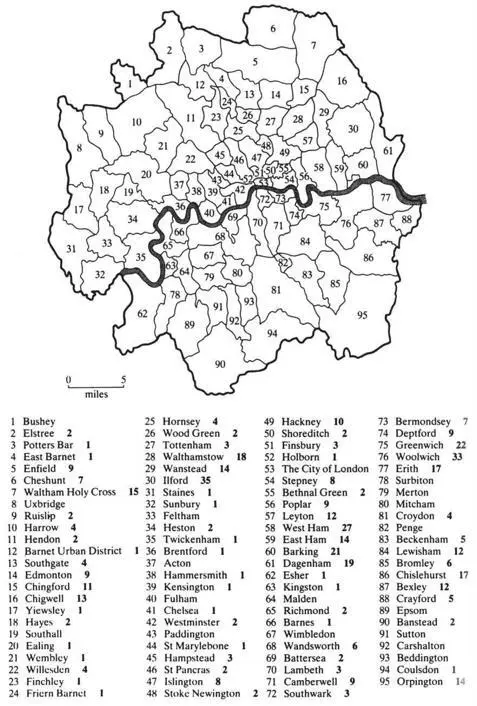

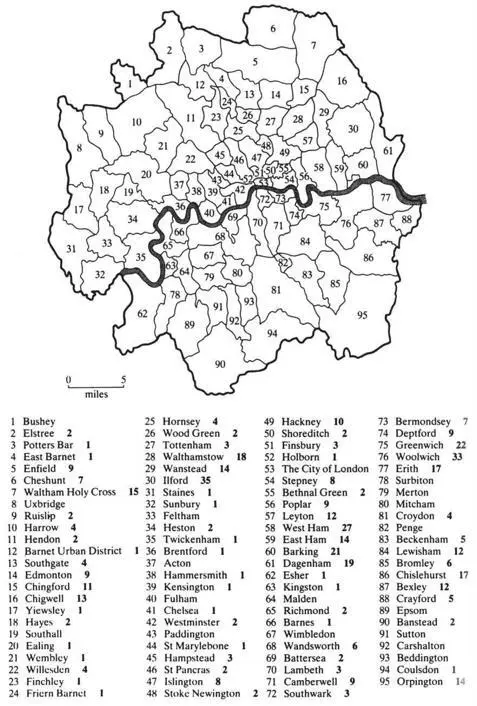

Where the V-2s landed in London

The map on p. 384 shows the London Civil Defence Region as it was in September 1944. The map shows all the boroughs within the Region, identified by numbers, to which the key is given above. The number of V-2s which landed in each borough is given in bold type to the right of its name.

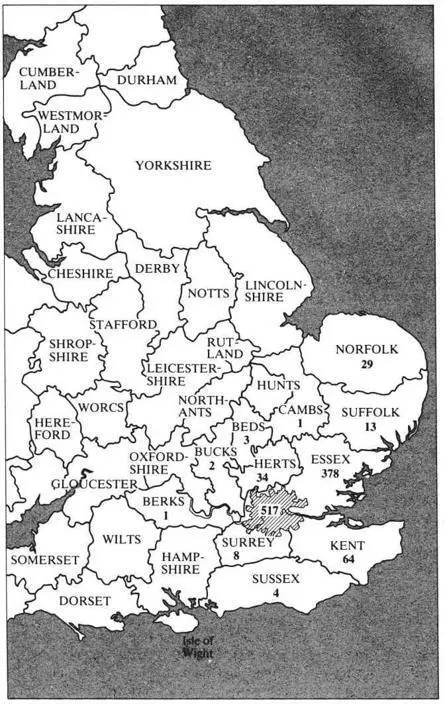

Where the V-2s landed outside London

The map on p. 385 shows all the counties in which V-2s landed, the county names and boundaries being those which existed in September 1944. The number of V-2s in each county, excluding any which landed in any part of it included in the London Civil Defence Region, is shown below its name.

This book is based upon material drawn from the following sources: published books and pamphlets, contemporary and subsequent newspaper and magazine articles and reports, a wide range of official documents in the Public Record Office and elsewhere (from statements prepared for publication to minutes and memoranda which were then highly secret), diaries and letters written at the time, and contributions specially written for me following a public appeal in the press for recollections of the V-1s and V-2s. The place of publication of books is London unless otherwise stated. Where the source of a quotation is obvious from the text (e.g. if a particular issue of a specific newspaper is named) this information is not repeated in the ‘Detailed references’ section below. In making use of official documents it should be noted that more than one copy may exist, under different file references. Where a single file (such as PREM 3/111, which proved particularly useful) contains a great many relevant documents I have given the written folio number, the later numbers being the more recent. I used two documents constantly. ‘Report of Attacks on this Country by… Long-Range Rockets… to March 29th 1945’ in File Air 20/3439 includes a list of casualties for each borough in London, and each affected county outside London, and, at Appendix ‘B’ a list of ‘outstanding incidents’. File HO 202/10 contains a series of weekly reports numbered from 221 to 250, giving the total number of incidents with notes about items of special interest. Wherever no other source is indicated it can be assumed that the figures in the text came from these documents. File HO 191/198 contains lists of incidents, giving precise time and map reference, a summary of damage caused and other essential facts, for incidents 1—26, 91—123 and 124—160. These have provided additional information given in the text for the periods covered and are not separately identified below.

Books, pamphlets and articles

After the Battle, no. 6, ‘The V Weapons’, Battle of Britain Prints International, London E15, 1974

‘Air Raids on Norfolk’, in Britannia, no. 29, February 1947

Angell, Joseph Warner, ‘Guided Missiles Could Have Won’, in Atlantic Monthly (Boston, Mass., USA), vol. 189, January 1952

Читать дальше

![Traudl Junge - Hitler's Last Secretary - A Firsthand Account of Life with Hitler [aka Until the Final Hour]](/books/416681/traudl-junge-hitler-s-last-secretary-a-firsthand-thumb.webp)