Although the history of Vladimir Prison started in the eighteenth century during the rule of Catherine the Great, its main buildings were built later, in the middle of the nineteenth century. 63In 1906, after the 1905 Revolution, it became a special prison for political convicts. From the 1930s on, and increasingly after World War II, Vladimir Prison was used for political prisoners of great state importance. Its official name was “Special MGB Prison No. 2” (Lubyanka Prison was No. 1). In the late 1940s and 1950s, citizens of many countries were kept there. Besides Russians, there were former ministers of the Baltic countries (and their wives, in separate cells without knowledge of the fate of their husbands), Germans, French, Swiss, and others. Among the Baltic prisoners was the former Latvian minister of foreign affairs Wilhelm Munters and his wife Natalia, whom Sudoplatov kidnapped in Riga in June 1940 and secretly transported to Russia. 64At first Munters and his wife were transferred to Voronezh in central Russia, where Munters was appointed a professor at the local university. On June 28, 1941, six days after the beginning of the war with the Nazis, the couple was arrested. After a trial, they, along with some other former Baltic ministers and their family members, were tried and put in the Kirov Internal Prison. Later, in 1952, all of them were retried, received twenty-five years’ imprisonment, and were kept in Vladimir Prison under numbers (Wilhelm and Natalia Munters, under Nos. 7 and 8, correspondingly) from April 1952 until their release in August 1954. 65Most of the foreigners were innocent people like Munters, sentenced to ten to twenty-five years’ imprisonment according to Article 58 of the Russian Criminal Code. But real Soviet criminals like Mairanovsky, Sudoplatov, Eitingon, and some other Beria men (who were not imprisoned for their real crimes), 66as well as German and Austrian war criminals, were also there.

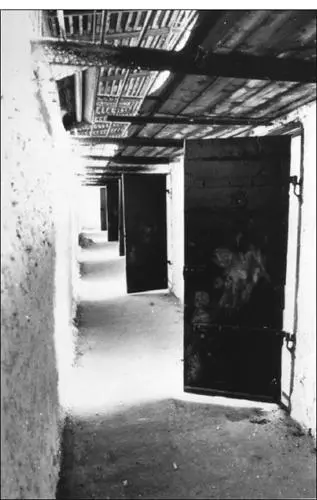

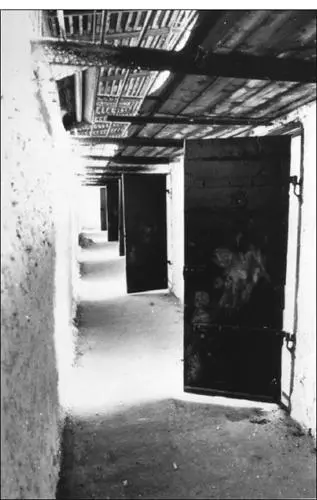

A corridor inside Vladimir Prison (1990). (Photo from Memorial’s Archive [Moscow])

According to the memoirs of a former prisoner, a Finn named Unto Parvilahti, among the Russians was Mairanovsky’s colleague Professor Grigory Liberman, a chemist who had specialized on poison gases and presumably had a general’s rank. 67Liberman was Academician Ipatieff’s pupil at the Artillery Academy laboratory on poison gases and was a specialist on methods of obtaining lewisite. 68This substance, dichloro (2-chlorovinyl) arsine, was developed in the United States during World War I but was never actually used. As Parvilahti recalled, Liberman, whom he met in prison briefly because of a mistake by the guards, told him that he had been arrested after Lenin’s death in 1924 and kept in prisons since then. During some of those years, he was allowed to work in a secret chemical laboratory under NKVD control, but after an accident in the lab, Liberman was put in solitary confinement in Vladimir Prison.

This seems to be true. According to Liberman’s prisoner card in Vladimir Prison, he was arrested in 1935 and sentenced five years later, in 1940, on charges of treason against the Motherland and participation in a terrorist organization (Document 19, Appendix II). However, there is a discrepancy between the charges for the arrest (point 14 in the card) and conviction (the back side of the card). In the first case, the following paragraphs of the Criminal Code are mentioned: 58-1a (treason against the Motherland), 58-7 (counterrevolutionary activity in a state institution), 58-8 (terrorist acts against governmental figures), and 58-11 (organization of terrorist acts or a membership in a counterrevolutionary group). In the second, Articles 58-1b (treason against the Motherland committed by a military person), 58-7, and 58-8 are mentioned. The problem is that persons charged with the paragraph 58-1b were punished by death. On May 26, 1947, a special decree of the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Council replaced the punishment by death with twenty-five-year imprisonment (the death penalty was restored in 1950). According to the prisoner card, on October 13, 1947, Liberman was brought to Vladimir Prison. Therefore, it looks as though he was tried again between May and October 1947, sentenced to imprisonment instead of being shot, and put in Vladimir Prison where he was kept in solitary confinement, probably under a number. For some reason, his term was not increased from fifteen to twenty-five years. In January–February 1949, Liberman was brought to Lefortovo Prison in Moscow, possibly to testify against newly arrested colleagues or German specialists. In March 1950, after the end of his fifteen-year term of imprisonment, Liberman was sent into exile to the Krasnoyarsk Region in Siberia.

Among the German prisoners, there was another Mairanovsky colleague, one of the most infamous medical experimenters in Auschwitz, Dr. Carl Clauberg. 69In 1943, Clauberg reported to Himmler that through the injection of supercooled carbon dioxide into the fallopian tubes, with a staff of ten men he could sterilize as many as 1,000 women per day. 70Several thousand Jews and Gypsies were sterilized at Auschwitz by this method under his supervision. 71In 1945, he continued his experiments in Ravensbruck. On June 24, 1945, Clauberg was arrested by the SMERSH Third Directorate (Military Counterintelligence) and sent to Moscow (Clauberg’s prisoner card; Document 20, Appendix II). I wonder if his specific knowledge regarding women’s sterilization obtained in the medical block of Auschwitz and Ravensbruck, and evidently discussed during interrogations, was later used in Mairanovsky’s or some other MGB laboratory.

On July 3, 1948, Clauberg was tried by the OSO and sentenced to twenty-five years’ imprisonment according the secret Decree of the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Council On the Punishment of the Nazi-German Criminals Guilty of Killing and Torturing Soviet Civilians and Prisoners of War, Spies and Traitors of the Motherland and Those Who Helped Them, dated April 19, 1943. Evidently, there were Soviet citizens among the victims of Clauberg’s experiments. The same July, Clauberg was transferred to Vladimir Prison. Possibly, he was kept under a number like Boris Men’shagin (Prisoner No. 29), the other prisoner also punished from April 19, 1943, under the same decree. In 1954–1957, all Germans and Austrians were released irrespective of their crimes and repatriated to their native countries. Clauberg was among them. He returned to Germany in 1955 and for some time practiced medicine under his own name. He openly boasted of his achievements in Auschwitz. Then Clauberg was arrested in the city of Kiel and died in 1957 in a prison hospital waiting for a new trial.

In 1948, sixty-year-old Dr. Heinrich Zeiss, the German specialist on bacteriological weapons whom I mentioned in connection with the 1930s Moscow trials and who had been expelled from Moscow in 1933, also ended up in Vladimir Prison. On July 10, 1948, he was condemned to twenty-five years’ imprisonment as a German spy (Zeiss’s prisoner card; Document 21, Appendix II). On March 31, 1949, he died there.

Before the mid-1950s, many prisoners were kept in solitary confinement. At that time, Vladimir Prison had cells for approximately 800 prisoners; in 1960, 200 new cells were added. The most prominent prisoners were kept in cells on the first floor of Corpus 2. As I have already mentioned, many of them were given numbers after they had been investigated by the MGB Department for Investigation of Especially Important Cases and convicted by the OSO. I personally knew a former prisoner, Men’shagin, who spent almost twenty-five years in solitary confinement, first in Lubyanka and then in Vladimir Prison. He was found “guilty” in 1951 of having witnessed the German exhumation in 1943 of Polish officers massacred by the NKVD in Katyn in 1940. For seven years, this man was Number 29 instead of having a name. 72There are two prisoner cards for Men’shagin in the Vladimir Prison file: one without a name but with the No. 29, and another, with Men’shagin’s full name.

Читать дальше