While Levina was in jail, her husband, professor of pathologic physiology Lev Levin, was persecuted as a Jew. Her son Mikhail (1921–1992), who later became a well-known radio physicist, was arrested even earlier, in 1944. 238He was a close friend of Academician Sakharov from their university years, and Sakharov mentioned Mikhail Levin in his memoirs with warm feeling: “Only one physicist in all of the USSR came to see me (and twice) in [exile in] Gorky without official permission—my former university classmate, Misha Levin.” 239In 1944, Levin, together with a group of friends, was charged with an attempt on Stalin’s life. All of them lived in the center of Moscow in apartment buildings on Arbat Street, right on the auto route Stalin and his guards used to go back and forth from Stalin’s dacha in the Moscow suburbs (where Stalin lived) to the Kremlin. During interrogations, Mikhail Levin managed to persuade the NKGB investigators that the accusation was complete nonsense. The attempt was physically impossible: The windows of all the rooms where the accused lived faced closed yards and not Arbat Street, and, therefore, it was not possible to shoot from the windows at passing cars. Naturally, the arrested were not released but sentenced to imprisonment in labor camps. Mikhail Levin spent a year in an institute for imprisoned scientists, the so-called sharashka . Although he was released from prison in 1945, Levin was forced to live in Gorky, the future location of Academician Sakharov’s exile in the 1980s. Only in 1956 was Levin allowed to return to Moscow, where he started to work at the Academy Radiotechnical Institute.

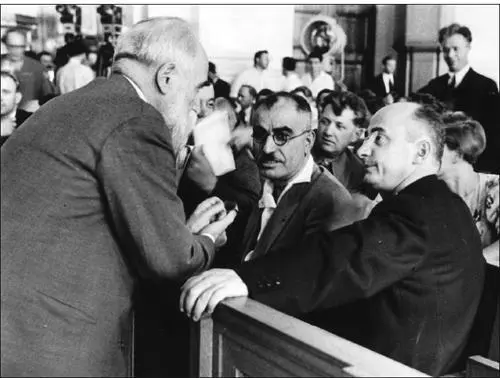

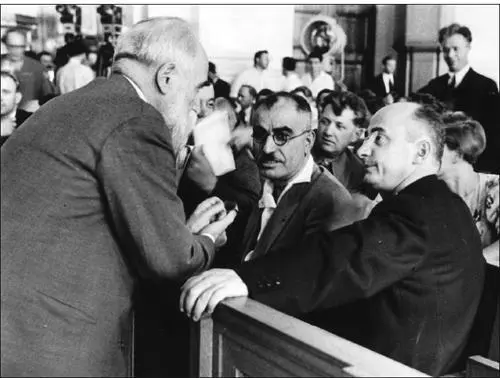

The Interior (NKVD) Commissar Lavrentii Beria at a meeting, 1938 (right figure, wearing pince-nez). In the late 1930s to the early 1940s, Laboratory No. 1 was subordinated directly to Beria. (Photo from the Russian State Archive of Cinema and Photo Documents [Moscow])

I was lucky to have been acquainted with Dr. Levin. In the summer of 1980, we rented houses not far from each other at a resort town called Narva in Estonia, where we spent a month with our children. Dr. Levin’s encyclopedic knowledge of European and Russian history was amazing. Also, he was a poet.

In 1949, the famous physiologist and academician Lina Stern was arrested in connection with the anti-Semitic “Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee case.” 240In 1925, Stern moved from Switzerland, where she was a professor at Geneva University, to the USSR. 241From 1925 until her arrest, she was a professor at the Second Moscow Medical Institute and director (from 1929) of the Institute of Physiology. She was the only woman to be a member of both Soviet academies, the Academy of Sciences and the Academy of Medical Sciences. The actor Mikhoels chaired the JAC, and Dr. Stern was a member of this committee.

The JAC case was initiated by reports of MGB minister Abakumov to the Central Committee and Council of Ministers in January and March 1948 about the “testimonies” of Isaak Goldstein and another arrested Jewish prisoner, Zakhar Grinberg, who was a senior scientist at the Academy Institute of World Literature. Dr. Grinberg, a friend of Goldstein, was the closest aide of Solomon Mikhoels in the JAC on matters concerning the Jewish scientific intelligentsia. 242In his reports, Abakumov claimed that the “testimonies” of Goldstein and Grinberg showed that the JAC was involved in the movement toward Jewish nationalism. These false “testimonies” were signed by Goldstein after torture. 243Later, on October 2, 1953, Goldstein wrote from Vladimir Prison: “In total, I was beaten eight times… Exhausted by these day-and-night interrogations, terrorized by tortures, swearing, and threats, I fell into a deep despair and total moral miasma, and started to incriminate myself and others in very serious crimes.” 244

Abakumov personally visited Lefortovo Prison to witness the “confession” of Goldstein. The final version of the “confession” was prepared by the deputy head of Abakumov’s secretariat, Colonel Yakov Broverman, and sent to Stalin. It said that Mikhoels, supposedly on behalf of his American friends, ordered Goldstein to get close to Svetlana Stalina through her Jewish husband, Grigory Moroz. 245

Finally, in the official MGB document to the Politburo “On the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee,” dated March 26, 1948, the MGB (i.e., Abakumov) accused the JAC of anti-Soviet nationalistic activity and contacts with the American secret services. On November 20, 1948, the Politburo approved a document in which the MGB was ordered to dissolve the JAC. At the end of 1948, the arrests of JAC members started. 246Stalin appointed a Politburo member, Georgii Malenkov to supervise the JAC case.

Even family members of Soviet leaders were not safe from arrest and investigation. As “honorary academician” and the second in command in the Soviet Union, Vyacheslav Molotov recalled in his memoirs, in 1948 at a Politburo meeting Stalin ordered Molotov to divorce his wife, Polina Zhemchuzhina (1897–1970), a candidate member of the Central Committee. “At the end of 1948 we were divorced. But in 1949, in February [in fact, on January 21] she was arrested,” recalled Molotov. 247Zhemchuzhina was accused of long-standing connection with the Jewish nationalists: She was a Jewess by origin and was considered to be a part of a Jewish plot within the JAC case.

Before her arrest, Zhemchuzhina was expelled from the Party at a Central Committee meeting. At first Molotov abstained, but after several days, on January 20, 1949, he wrote a top-secret note addressed to Stalin: “I hereby declare that after thinking the matter over I now vote in favor of the Central Committee’s decision… Furthermore, I acknowledge that I was gravely at fault in not restraining in time a person near to me from taking false steps and from dealings with such anti-Soviet nationalists as Mikhoels.” 248

The note did not prevent the punishment of Molotov for his hesitation and abstention: He was dismissed from his post of foreign minister and another “honorary academician,” General Prosecutor Andrei Vyshinsky, replaced him.

Besides torture, Zhemchuzhina’s investigation involved another sordid tactic. Two male prisoners were forced to “testify” that they had participated in “group sex” with the elderly Bolshevik woman. 249Finally, Zhemchuzhina was tried by the OSO, condemned to five-year exile, and sent to the distant Kustanai Region in Kazakhstan as “Prisoner No. 12.”

Concerning the accusations against Lina Stern, besides her membership in the JAC, there was one more “incriminating” fact about her participation in the “Jewish plot.” She was connected with the Allilueva case through Iosif Moroz, the father of Stalin’s son-in-law, Grigory, who had already been convicted for alleged Jewish nationalistic “anti-Soviet propaganda.” In 1945, Lina Stern had employed Moroz as her deputy director at the Institute of Physiology. At the time of the arrest, Stern was seventy-two years old. At the interrogation, when MGB minister Abakumov roared at her, “You old whore!” she replied: “So that’s the way a minister speaks to an Academician.” 250

In late March 1950, the investigation of the JAC case was completed. Grinberg died in prison before that, on December 22, 1949 (officially of a heart attack). The Military Collegium of the USSR Supreme Court heard the case for two months, starting on May 8, 1952. All defendants were accused of nationalistic and espionage activity for the United States. In the courtroom, four prisoners, including Stern, recanted the statements they made during interrogations and denied their guilt. 251On July 18, 1952, the court convicted fifteen members of the JAC, thirteen men and two women, all of them being famous Jewish writers, poets, actors, translators, and so on, to death. The chair of the collegium, Justice Lieutenant General V. Cheptsov, tried in vain to appeal to Chief Prosecutor General Safonov and then to Georgii Malenkov, insisting on the necessity of returning the case for further investigation. 252He also sent Solomon Lozovsky’s (the main defendant) statement after sentencing with the denial of guilt to Stalin (Lozovsky was an Old Bolshevik, whom Stalin had known personally for many years). No new instructions followed from the Politburo, and the convicts were executed on August 12, 1952. Among them was Boris Shimeliovich (1892–1952), chief doctor of the Botkin Central Clinical Hospital in Moscow. His arrest and conviction was a prelude to the Doctors’ Plot case.

Читать дальше