David Deutch - The Fabric of Reality

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «David Deutch - The Fabric of Reality» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. ISBN: , Жанр: Физика, Философия, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Fabric of Reality

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:0-7139-9061-9

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 2

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Fabric of Reality: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Fabric of Reality»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Fabric of Reality — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Fabric of Reality», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

A ‘theory of everything’ which excludes a specification of the initial state of the universe is not a complete description of physical reality because it provides only laws of motion; and laws of motion, by themselves, make only conditional predictions. That is, they never state categorically what happens, but only what will happen at one time given what was happening at another time. Only if a complete specification of the initial state is provided can a complete description of physical reality in principle be deduced. Current cosmological theories do not provide a complete specification of the initial state, even in principle, but they do say that the universe was initially very small, very hot and very uniform in structure. We also know that it cannot have been perfectly uniform because that would be incompatible, according to the theory, with the distribution of galaxies we observe across the sky today. The initial variations in density, ‘lumpiness’, would have been greatly enhanced by gravitational clumping (that is, relatively dense regions would have attracted more matter and become denser), so they need only have been very slight initially. But, slight though they were, they are of the greatest significance in any reductionist description of reality, because almost everything that we see happening around us, from the distribution of stars and galaxies in the sky to the appearance of bronze statues on planet Earth, is, from the point of view of fundamental physics, a consequence of those variations. If our reductionist description is to cover anything more than the grossest features of the observed universe, we need a theory specifying those all-important initial deviations from uniformity.

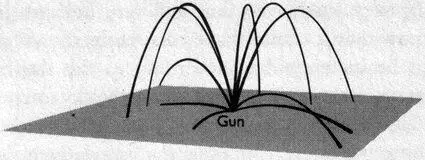

Let me try to restate this requirement without the reductionist bias. The laws of motion for any physical system make only conditional predictions, and are therefore compatible with many possible histories of that system. (This issue is independent of the limitations on predictability that are imposed by quantum theory, which I shall discuss in the next chapter.) For instance, the laws of motion governing a cannon-ball fired from a gun are compatible with many possible trajectories, one for every possible direction and elevation in which the gun could have been pointing when it was fired (Figure 1.2). Mathematically, the laws of motion can be expressed as a set of equations called the equations of motion. These have many different solutions, one describing each possible trajectory. To specify which solution describes the actual trajectory, we must provide supplementary data — some data about what actually happens. One way of doing that is to specify the initial state, in this case the direction in which the gun was pointing. But there are other ways too. For example, we could just as well specify the final state — the position and direction of motion of the cannon-ball at the moment it lands. Or we could specify the position of the highest point of the trajectory. It does not matter what supplementary data we give, so long as they pick out one particular solution of the equations of motion. The combination of any such supplementary data with the laws of motion amounts to a theory that describes everything that happens to the cannon-ball between firing and impact.

FIGURE 1.2. Some possible trajectories of a cannon-ball fired from a gun. Each trajectory is compatible with the laws of motion, but only one of them is the trajectory on a particular occasion.

Similarly, the laws of motion for physical reality as a whole would have many solutions, each corresponding to a distinct history. To complete the description, we should have to specify which history is the one that has actually occurred, by giving enough supplementary data to yield one of the many solutions of the equations of motion. In simple cosmological models at least, one way of giving such data is to specify the initial state of the universe. But alternatively we could specify the final state, or the state at any other time; or we could give some information about the initial state, some about the final state, and some about states in between. In general, the combination of enough supplementary data of any sort with the laws of motion would amount to a complete description, in principle, of physical reality.

For the cannon-ball, once we have specified, say, the final state it is straightforward to calculate the initial state, and vice versa, so there is no practical difference between different methods of specifying the supplementary data. But for the universe most such calculations are intractable. I have said that we infer the existence of ‘lumpiness’ in the initial conditions from observations of ‘lumpiness’ today. But that is exceptional: most of our knowledge of supplementary data — of what specifically happens — is in the form of high-level theories about emergent phenomena, and is therefore by definition not practically expressible in the form of statements about the initial state. For example, in most solutions of the equations of motion the initial state of the universe does not have the right properties for life to evolve from it. Therefore our knowledge that life has evolved is a significant piece of the supplementary data. We may never know what, specifically, this restriction implies about the detailed structure of the Big Bang, but we can draw conclusions from it directly. For example, the earliest accurate estimate of the age of the Earth was made on the basis of the biological theory of evolution, contradicting the best physics of the day. Only a reductionist prejudice could make us feel that this was somehow a less valid form of reasoning, or that in general it is more ‘fundamental’ to theorize about the initial state than about emergent features of reality.

Even in the domain of fundamental physics, the idea that theories of the initial state contain our deepest knowledge is a serious misconception. One reason is that it logically excludes the possibility of explaining the initial state itself — why the initial state was what it was — but in fact we have explanations of many aspects of the initial state. And more generally, no theory of time can possibly explain it in terms of anything ‘earlier’; yet we do have deep explanations, from general relativity and even more from quantum theory, of the nature of time (see Chapter 11).

Thus the character of many of our descriptions, predictions and explanations of reality bear no resemblance to the ‘initial state plus laws of motion’ picture that reductionism leads to. There is no reason to regard high-level theories as in any way ‘second-class citizens’. Our theories of subatomic physics, and even of quantum theory or relativity, are in no way privileged relative to theories about emergent properties. None of these areas of knowledge can possibly subsume all the others. Each of them has logical implications for the others, but not all the implications can be stated, for they are emergent properties of the other theories’ domains. In fact, the very terms ‘high level’ and ‘low level’ are misnomers. The laws of biology, say, are high-level, emergent consequences of the laws of physics. But logically, some of the laws of physics are then ‘emergent’ consequences of the laws of biology. It could even be that, between them, the laws governing biological and other emergent phenomena would entirely determine the laws of fundamental physics. But in any case, when two theories are logically related, logic does not dictate which of them we ought to regard as determining, wholly or partly, the other. That depends on the explanatory relationships between the theories. The truly privileged theories are not the ones referring to any particular scale of size or complexity, nor the ones situated at any particular level of the predictive hierarchy — but the ones that contain the deepest explanations. The fabric of reality does not consist only of reductionist ingredients like space, time and subatomic particles, but also of life, thought, computation and the other things to which those explanations refer. What makes a theory more fundamental, and less derivative, is not its closeness to the supposed predictive base of physics, but its closeness to our deepest explanatory theories.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Fabric of Reality»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Fabric of Reality» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Fabric of Reality» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.