David Deutch - The Fabric of Reality

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «David Deutch - The Fabric of Reality» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. ISBN: , Жанр: Физика, Философия, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Fabric of Reality

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:0-7139-9061-9

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 2

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Fabric of Reality: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Fabric of Reality»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Fabric of Reality — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Fabric of Reality», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

But is this effect really an impediment to the accurate rendering of time travel? Normally, mimicking an environment’s actual behaviour is not the aim of virtual reality: what counts is that it should respond accurately. As soon as you begin to play tennis on the rendered Wimbledon Centre Court, you make it behave differently from the way the real one is behaving. But that does not make the rendering any less accurate. On the contrary, that is what is required for accuracy. Accuracy, in virtual reality, means the closeness of the rendered behaviour to that which the original environment would exhibit if the user were present in it. Only at the beginning of the rendering does the rendered environment’s state have to be faithful to the original. Thereafter it is not its state but its responses to the user’s actions that have to be faithful. Why is that ‘paradoxical’ for renderings of time travel but not for other renderings — for instance, for renderings of ordinary travel?

It seems paradoxical because in renderings of past-directed time travel the user plays a unique double, or multiple, role. Because of the looping that is involved, where for instance one or more copies of the user may co-exist and interact, the virtual-reality generator is in effect required to render the user while simultaneously responding to the user’s actions. For example, let us imagine that I am the user of a virtual-reality generator running a time-travel-rendering program. Suppose that when I switch on the program, the environment that I see around me is a futuristic laboratory. In the middle there is a revolving door, like those at the entrances of large buildings, except that this one is opaque and is almost entirely enclosed in an opaque cylinder. The only way in or out of the cylinder is a single entrance cut in its side. The door within revolves continuously. It seems at first sight that there is little one can do with this device except to enter it, go round one or more times with the revolving door, and come out again. But above the entrance is a sign: ‘Pathway to the Past’. It is a time machine, a fictional, virtual-reality one. But if a real past-directed time machine existed it would, like this one, not be an exotic sort of vehicle but an exotic sort of place. Rather than drive or fly it to the past, one would take a certain path through it (perhaps using an ordinary space vehicle) and emerge at an earlier time.

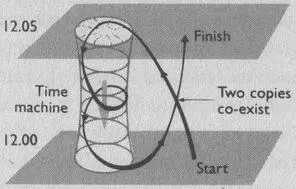

FIGURE 12.1 Spacetime path taken by a time traveller.

On the wall of the simulated laboratory there is a clock, initially showing noon, and by the cylinder’s entrance there are some instructions. By the time I have finished reading them it is five minutes past noon, both according to my own perception and according to the clock. The instructions say that if I enter the cylinder, go round once with the revolving door, and emerge, it will be five minutes earlier in the laboratory. I step into one of the compartments of the revolving door. As I walk round, my compartment closes behind me and then, moments later, reaches the entrance again. I step out. The laboratory looks much the same except — what? What exactly should I expect to experience next, if this is to be an accurate rendering of past-directed time travel?

Let me backtrack a little first. Suppose that by the entrance there is a switch whose two positions are labelled ‘interaction on ’ and ‘interaction off ’. Initially it is at ‘interaction off ’. This setting does not allow the user to participate in the past, but only to observe it. In other words, it does not provide a full virtual-reality rendering of the past environment, but only image generation.

With this simpler setting at least, there is no ambiguity or paradox about what images ought to be generated when I emerge from the revolving door. They are images of me, in the laboratory, doing what I did at noon. One reason why there is no ambiguity is that I can remember those events, so I can test the images of the past against my own recollection of what happened. By restricting our analysis to a small, closed environment over a short period, we have avoided the problem analogous to that of finding out what Julius Caesar was really like, which is a problem about the ultimate limits of archaeology rather than about the inherent problems of time travel. In our case, the virtual-reality generator can easily obtain the information it needs to generate the required images, by making a recording of everything I do. Not, that is, a recording of what I do in physical reality (which is simply to lie still inside the virtual-reality generator), but of what I do in the virtual environment of the laboratory. Thus, the moment I emerge from the time machine, the virtual-reality generator ceases to render the laboratory at five minutes past noon, and starts to play back its recording, starting with images of what happened at noon. It displays this recording to me with the perspective adjusted for my present position and where I am looking, and it continuously readjusts the perspective in the usual way as I move. Thus, I see the clock showing noon again. I also see my earlier self, standing in front of the time machine, reading the sign above the entrance and studying the instructions, exactly as I did five minutes ago. I see him, but he cannot see me. No matter what I do, he — or rather it, the moving image of me — does not react to my presence in any way. After a while, it walks towards the time machine.

If I happen to be blocking the entrance, my image will nevertheless make straight for it and walk in, exactly as I did, for if it did anything else it would be an inaccurate image. There are many ways in which an image generator can be programmed to handle a situation where an image of a solid object has to pass through the user’s location. For instance, the image could pass straight through like a ghost, or it could push the user irresistibly away. The latter option gives a more accurate rendering because then the images are to some extent tactile as well as visual. There need be no danger of my getting hurt as my image knocks me aside, however abruptly, because of course I am not physically there. If there is not enough room for me to get out of the way, the virtual-reality generator could make me flow effortlessly through a narrow gap, or even teleport me past an obstacle.

It is not only the image of myself on which I can have no further effect. Because we have temporarily switched from virtual reality to image generation, I can no longer affect anything in the simulated environment. If there is a glass of water on a table I can no longer pick it up and drink it, as I could have before I passed through the revolving door to the simulated past. By requesting a simulation of non-interactive, past-directed time travel, which is effectively a playback of specific events five minutes ago, I necessarily relinquish control over my environment. I cede control, as it were, to my former self.

As my image enters the revolving door, the time according to the clock has once again reached five minutes past twelve, though it is ten minutes into the simulation according to my subjective perception. What happens next depends on what I do. If I just stay in the laboratory, the virtual-reality generator’s next task must be to place me at events that occur after five minutes past twelve, laboratory time. It does not yet have any recordings of such events, nor do I have any memories of them. Relative to me, relative to the simulated laboratory and relative to physical reality, those events have not yet happened, so the virtual-reality generator can resume its fully interactive rendering. The net effect is of my having spent five minutes in the past without being able to affect it, and then returning to the ‘present’ that I had left, that is, to the normal sequence of events which I can affect.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Fabric of Reality»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Fabric of Reality» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Fabric of Reality» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.