David Deutch - The Fabric of Reality

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «David Deutch - The Fabric of Reality» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. ISBN: , Жанр: Физика, Философия, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Fabric of Reality

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:0-7139-9061-9

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 2

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Fabric of Reality: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Fabric of Reality»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Fabric of Reality — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Fabric of Reality», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The best-known physical manifestation of universality is an area of technology that has been mooted for decades but is only now beginning to take off, namely virtual reality. The term refers to any situation in which a person is artificially given the experience of being in a specified environment. For example, a flight simulator — a machine that gives pilots the experience of flying an aircraft without their having to leave the ground — is a type of virtual-reality generator. Such a machine (or more precisely, the computer that controls it) can be programmed with the characteristics of a real or imaginary aircraft. The aircraft’s environment, such as the weather and the layout of airports, can also be specified in the program. As the pilot practises flying from one airport to another, the simulator causes the appropriate images to appear at the windows, the appropriate jolts and accelerations to be felt, the corresponding readings to be shown on the instruments, and so on. It can incorporate the effects of, for example, turbulence, mechanical failure and proposed modifications to the aircraft. Thus a flight simulator can give the user a wide range of piloting experiences, including some that no real aircraft could: the simulated aircraft could have performance characteristics that violate the laws of physics: it could, for instance, fly through mountains, faster than light or without fuel.

Since we experience our environment through our senses, any virtual-reality generator must be able to manipulate our senses, overriding their normal functioning so that we can experience the specified environment instead of our actual one. This may sound like something out of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, but of course technologies for the artificial control of human sensory experience have been evolving for thousands of years. All techniques of representational art and long-distance communication may be thought of as ‘overriding the normal functioning of the senses’. Even prehistoric cave paintings gave the viewer something of the experience of seeing animals that were not actually there. Today we can do that much more accurately, using movies and sound recordings, though still not accurately enough for the simulated environment to be mistaken for the original.

I shall use the term image generator for any device, such as a planetarium, a hi-fi system or a spice rack, which can generate specifiable sensory input for the user: specified pictures, sounds, odours, and so on all count as ‘images’. For example, to generate the olfactory image (i.e. the smell) of vanilla, one opens the vanilla bottle from the spice rack. To generate the auditory image (i.e. the sound) of Mozart’s 20th piano concerto, one plays the corresponding compact disc on the hi-fi system. Any image generator is a rudimentary sort of virtual-reality generator, but the term ‘virtual reality’ is usually reserved for cases where there is both a wide coverage of the user’s sensory range, and a substantial element of interaction (‘kicking back’) between the user and the simulated entities.

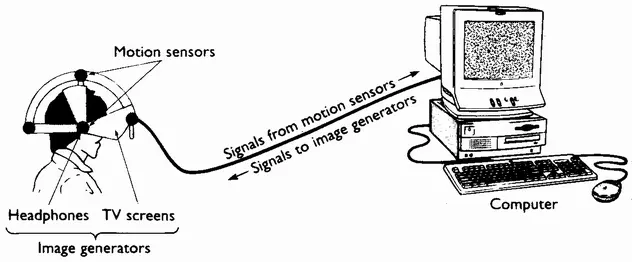

Present-day video games do allow interaction between the player and the game objects, but usually only a small fraction of the user’s sensory range is covered. The rendered ‘environment’ consists of images on a small screen, and a proportion of the sounds that the user hears. But virtual-reality video games more worthy of the term do already exist. Typically, the user wears a helmet with built-in headphones and two television screens, one for each eye, and perhaps special gloves and other clothing lined with electrically controlled effectors (pressure-generating devices). There are also sensors that detect the motion of parts of the user’s body, especially the head. The information about what the user is doing is passed to a computer, which calculates what the user should be seeing, hearing and feeling, and responds by sending appropriate signals to the image generators (Figure 5.1). When the user looks to the left or right, the pictures on the two television screens pan, just as a real field of view would, to show whatever is on the user’s left or right in the simulated world. The user can reach out and pick up a simulated object, and it feels real because the effectors in the glove generate the ‘tactile feedback’ appropriate to whatever position and orientation the object is seen in.

Game-playing and vehicle simulation are the main uses of virtual reality at present, but a plethora of new uses is envisaged for the near future. It will soon be commonplace for architects to create virtual-reality prototypes of buildings in which clients can walk around and try out modifications at a stage when they can be implemented relatively effortlessly. Shoppers will be able to walk (or indeed fly) around in virtual-reality supermarkets without ever leaving home, and without ever encountering crowds of other shoppers or listening to music they don’t like. Nor will they necessarily be alone in the simulated supermarket, for any number of people can go shopping together in virtual reality, each being provided with images of the others as well as of the supermarket, without any of them having to leave home. Concerts and conferences will be held without venues; not only will there be savings on the cost of the auditorium, and on accommodation and travel, but there is also the benefit that all the participants could be allowed to sit in the best seats simultaneously.

FIGURE 5.1 Virtual reality as it is implemented today.

If Bishop Berkeley or the Inquisition had known of virtual reality, they would probably have seized upon it as the perfect illustration of the deceitfulness of the senses, backing up their arguments against scientific reasoning. What would happen if the pilot of a flight simulator tried to use Dr Johnson’s test for reality? Although the simulated aircraft and its surroundings do not really exist, they do ‘kick back’ at the pilot just as they would if they did exist. The pilot can open the throttle and hear the engines roar in response, and feel their thrust through the seat, and see them through the window, vibrating and blasting out hot gas, in spite of the fact that there are no engines there at all. The pilot may experience flying the aircraft through a storm, and hear the thunder and see the rain driving against the windscreen, though none of those things is there in reality. What is outside the cockpit in reality is just a computer, some hydraulic jacks, television screens and loudspeakers, and a perfectly dry and stationary room.

Does this invalidate Dr Johnson’s refutation of solipsism? No. His conversation with Boswell could just as well have taken place inside a flight simulator. ‘I refute it thus ’, he might have said, opening the throttle and feeling the simulated engine kick back. There is no engine there. What kicks back is ultimately a computer, running a program that calculates what an engine would do if it were ‘kicked’. But those calculations, which are external to Dr Johnson’s mind, respond to the throttle control in the same complex and autonomous way as the engine would. Therefore they pass the test for reality, and rightly so, for in fact these calculations are physical processes within the computer, and the computer is an ordinary physical object — no less so than an engine — and perfectly real. The fact that it is not a real engine is irrelevant to the argument against solipsism. After all, not everything that is real has to be easy to identify. It would not have mattered, in Dr Johnson’s original demonstration, if what seemed to be a rock had later turned out to be an animal with a rock-like camouflage, or a holographic projection disguising a garden gnome. So long as its response was complex and autonomous, Dr Johnson would have been right to conclude that it was caused by something real, outside himself, and therefore that reality did not consist of himself alone.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Fabric of Reality»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Fabric of Reality» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Fabric of Reality» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.