It turns out (see below) that backward time travel is governed by the laws of quantum gravity, which are terra almost incognita, so we physicists don’t know for sure what is allowed and what not.

Chris made two specific choices for allowed and forbidden time travel—his rule set:

Rule 1: Physical objects and fields with three space dimensions, such as people and light rays, cannot travel backward in time from one location in our brane to another, nor can information that they carry. The physical laws or the actual warping of spacetime prevent it. This is true whether the objects are forever lodged in our brane or journey through the bulk in a three-dimensional face of a tesseract, from one point in our brane to another. So, in particular, Cooper can never travel to his own past.

Rule 2: Gravitational forces can carry messages into our brane’s past.

In the movie, rule 1 generates mounting tension. Murph grows older and older as Cooper lingers near Gargantua. With no possibility to travel backward in time there’s a growing danger he’ll never return to her.

Rule 2 gives Cooper hope. Hope that he can use gravity to transmit the quantum data backward in time to young Murph, so she can solve the Professor’s equation and figure out how to lift humanity off Earth.

How do these rules play out in Interstellar ?

Messaging Murph

When falling into and through the tesseract, Cooper truly does travel backward relative to our brane’s time, from the era when Murph is an old woman to the era when she is ten years old. He does this in the sense that, looking at Murph in the tesseract bedrooms, he sees her ten years old. And he can move forward and backward relative to our brane’s time (the bedroom’s time) in the sense that he can look at Murph at various bedroom times by choosing which bedroom to look into. This does not violate rule 1 because Cooper has not reentered our brane. He remains outside it, in the tesseract’s three-dimensional channel, and he looks into Murph’s bedroom via light that travels forward in time from Murph to him.

But just as Cooper can’t reenter our brane in Murph’s ten-year-old era, so he can’t send light to her. That would violate rule 1. The light could bring her information from Cooper’s personal past, which is her future; information from the era when she is an old woman—backward-in-time information from one location in our brane to another. So there must be some sort of one-way spacetime barrier between ten-year-old Murph in her bedroom and Cooper in the tesseract, rather like a one-way mirror or a black-hole horizon. Light can travel from Murph to Cooper but not from Cooper to Murph.

In my scientist’s interpretation of Interstellar , the one-way barrier has a simple origin: Cooper, in the tesseract, is always in ten-year-old Murph’s future. Light can travel toward the future from Murph to him. It can’t travel to the past from him to Murph.

However, gravity can surmount that one-way barrier, Cooper discovers. Gravitational signals can go backward in time from Cooper to Murph. We first see this when Cooper desperately pushes books out of Murph’s bookcase. Figure 30.1 shows a still from that scene of the movie.

Fig. 30.1. Cooper pushes on the world tube of a book with his right hand. [From Interstellar , used courtesy of Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.]

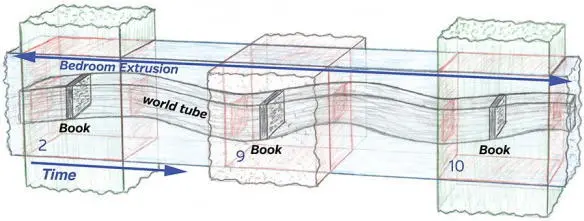

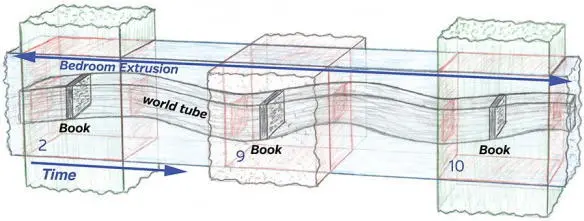

To explain this still, I must tell you a bit more about the bedroom extrusions, as Chris and Paul Franklin explained them to me. Let’s focus on the front blue extrusion in Figures 29.10 and 29.12, which I reproduce as Figure 30.2 with extraneous stuff removed. Recall that this extrusion is a set of vertical cross sections through Murph’s bedroom, traveling forward in bedroom time along the blue direction (rightward).

Fig. 30.2. The world tube of a book, within an extrusion of Murph’s bedroom. The book and its world tube are drawn much larger than they actually are. [My own hand sketch.]

Each object in the bedroom, for example each book, contributes to the bedroom’s extrusion. In fact, the book has its own extrusion, which travels forward in time along the blue-arrow direction as part of the bedroom’s larger extrusion. We physicists call a variant of this extrusion the book’s “world tube.” And we call the extrusion of each particle of matter in the book the particle’s “world line.” So the book’s world tube is a bundle of world lines of all the particles that make up the book. Chris and Paul also use this language. The thin lines that you see in the movie, running along the extrusions, are world lines of particles of matter in Murph’s bedroom.

In Figure 30.1, Cooper slams his fist on the book’s world tube over and over again, creating a gravitational force, which travels backward in time to the moment in Murph’s bedroom that he is seeing and then pushes on the book’s world tube. The book’s tube responds by moving. The tube’s motion appears to Cooper as an instantaneous response to his pushes. And the motion becomes a wave traveling leftward down the tube (Figure 30.2). [56] Why leftward? So the tube is always at the same transverse position at any specific moment of bedroom time. Think about it.

When the motion gets strong enough, the book falls out of the bookcase.

By the time Cooper has received the quantum data from TARS, he has mastered this means of communication. In the movie we see him pushing with his finger on the world tube of a watch’s second hand. His pushes produce a backward-in-time gravitational force, which makes the second-hand twitch in a Morse-encoded pattern that carries the quantum data. The tesseract stores the twitching pattern in the bulk so it repeats over and over again. When forty-year-old Murph returns to her bedroom three decades later, she finds the second hand still twitching, repeating over and over again the encoded quantum data that Cooper has struggled so hard to send her.

How does the backward-in-time gravitational force work? I’ll describe my physicist’s interpretation after I tell you what I know, or think I know, about backward time travel.

Time Travel Without a Bulk: What I Think I Know

In 1987, triggered by Carl Sagan (Chapter 14), I realized something amazing about wormholes. If wormholes are allowed by the laws of physics, then Einstein’s relativistic laws permit transforming them into time machines. The nicest example of this was discovered a year later by my close friend Igor Novikov, in Moscow, Russia. Igor’s example, Figure 30.3, shows that a wormhole’s transformation into a time machine might occur naturally, without the aid of intelligent beings.

In Figure 30.3, the bottom mouth of the wormhole is in orbit around a black hole and the upper mouth is far from the black hole. Because of the black hole’s intense gravitational pull, Einstein’s law of time warps dictates that time flow more slowly at the lower mouth than at the upper mouth. More slowly, that is, when compared along the path of gravity’s intense pull: the dashed purple path through the external universe. I presume, for concreteness, that this has produced a one-hour lag so when compared through the external universe, the bottom clock shown in the figure is one hour behind the top clock. And this time lag is continuing to grow.

Читать дальше