As dinner began I placed a microphone at the center of our round table and recorded our two-and-a-half-hour, free-wheeling conversation. This chapter is based on that recording, but I’ve paraphrased what people said—and they checked and approved my paraphrasing.

Our final consensus, easily reached, is that Cooper’s world is scientifically possible, but not very likely . It is very unlikely to happen, but it could. That’s why I labeled this chapter  for speculative.

for speculative.

Over wine and hors d’oevres, Jonah described his vision for Cooper’s world (Figure 11.1): Some combination of catastrophes has reduced the population of North America tenfold or more, and similarly on all other continents. We have become a largely agrarian society, struggling to feed and shelter ourselves. But ours is not a dystopia. Life is still tolerable and in some ways pleasant, with little amenities such as baseball continuing. However, we no longer think big. We no longer aspire to great things. We aspire to little more than just keeping life going.

Fig. 11.1. Aspects of life in Cooper’s world. Top : A baseball game with a dust storm on the horizon. Bottom : Cooper’s home and truck after the storm. [From Interstellar , used courtesy of Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.]

Most of us think the catastrophes are finished, that we humans are securing ourselves in this new world and things may start improving. But in reality the blight is so lethal, and leaps so quickly from crop to crop, that the human race is doomed within the lifetime of Cooper’s grandchildren.

What kind of catastrophes could have produced Cooper’s world? Our biologist experts offered a number of possible, but improbable, answers. Here are several:

Leadbetter:Today (2008) most people aren’t growing their own food. We’re dependent on a global system for growing and distributing food, and for distributing water. You could imagine that system breaking down due to some biological or geophysical catastrophe. As an example on a small scale, if there was no snow in the Sierra Nevada Mountains for a few consecutive years, there would be little drinking water in Los Angeles. Ten million people would be forced to migrate, and agricultural output in California would plummet. You can easily imagine much larger scale catastrophes. In Cooper’s world, with a vastly reduced population and a return to agrarian society, the production and distribution problems are lessened.

Simon:Another possible catastrophe: Over human history there has been a continual battle between us and pathogens (microbes that attack the human body or attack plants or other animals). We humans have developed a sophisticated immune system to deal with the pathogens that attack us directly. But the pathogens keep evolving and we’re always half a step behind them. At some point there could be a catastrophe where the pathogens change so fast that our immune systems can’t keep up.

Baltimore:For example, the AIDS virus could quickly evolve into a far more contagious form, one transmitted by coughing or breathing instead of sex.

Simon:The Earth’s ice caps, melting due to global warming, could release a long-dormant lethal pathogen from before the last ice age.

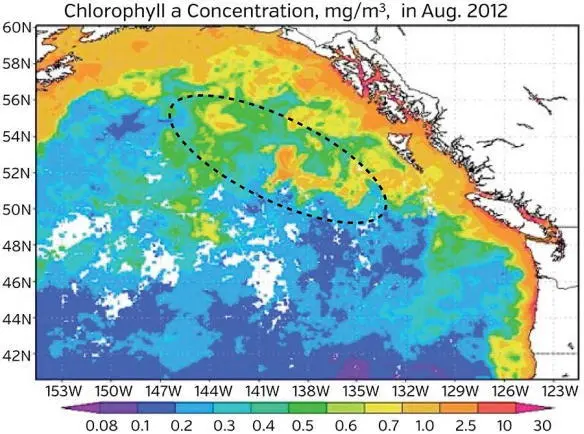

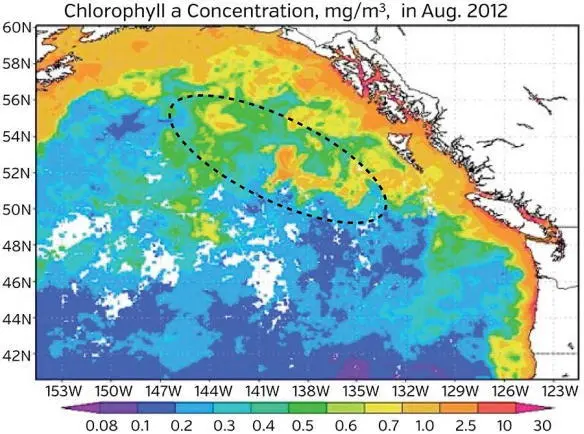

Leadbetter:Yet another scenario: People could panic about global warming. The warming is largely caused by increasing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. To save us, they might fertilize the Earth’s oceans to produce algae that will eat much of the atmosphere’s carbon dioxide via photosynthesis. A lot of iron, thrown into the oceans, could do the job. But there might be catastrophic unintended side effects. You might get some new kinds of algae that produce toxins (poison chemicals, not deadly life-forms) that poison the oceans. There would be a massive kill off of fish and plant life. Human civilization depends heavily on the oceans. This could be catastrophic for humans. Is it impossible? Not at all. Experiments have been done where iron was thrown locally into the ocean to produce algae—so much algae that it could be seen from space as green spots (Figure 11.2). Some of the algae that bloomed were of types never before known to science! We were lucky: the new algae were not noxious, but they might have been.

Fig. 11.2. Map of chlorophyll concentration (algae) after dumping 100 tons of iron sulphate into the ocean off the coast of British Columbia. Iron-stimulated algae growth produced the high algae concentration inside the dashed ellipse. [From Giovanni/Goddard Earth Sciences Data and Information Services Center/NASA.]

Meyerowitz:Ultraviolet light, streaming through our atmosphere’s ozone hole, could mutate your enormous bloom of algae so it creates new pathogens. These pathogens could wipe out plants in the ocean, and then jump to land and start wiping out crops.

Baltimore:When faced with catastrophes like these, our only hope for dealing with them is advanced science and technology. If, politically, we don’t invest in science and technology, or we hobble them by anti-intellectual ideologies such as denial of evolution, the very source of these catastrophes, we may find ourselves without the solutions we need.

And then there is blight —the consequence of many of these scenarios.

Blight is a general term for most any disease in a plant that is caused by a pathogen.

Baltimore:If you want something to wipe out humanity, there might be no better way than a blight that attacks plants. We are dependent on plants to eat. Yes, we can eat animals or fish instead, but they ate plants.

Meyerowitz:It might be sufficient for the blight just to kill off the grasses and nothing else. Grasses are the basis of most of our agriculture: rice, corn, barley, sorghum, wheat. And most animals that we eat feed on grasses.

Meyerowitz:We already live in a world where 50 percent of the food grown is destroyed by pathogens, and it’s much higher than that in Africa. Fungi, bacteria, viruses,… they all can be pathogens. The East Coast used to be covered with chestnut trees. They are no more. They were killed by a blight. The species of banana preferred by most people in the eighteenth century was wiped out by a blight. The replacement species, the Cavendish banana, today is being threatened by blight.

Kip:I thought that blights are specialists that attack only one narrow group of plants and don’t jump to others.

Leadbetter:There are also generalist blights. There seems to be a tradeoff between being a generalist that attacks many species and a specialist that attacks only a few. For the specialist blight, the lethality can be turned up really high; it can knock out, say, 99 percent of a very specific group of plants. For the generalist, the range of plants attacked is much broader, but its lethality for any one plant in that range might be much smaller. That’s a pattern we see again and again in Nature.

Читать дальше

for speculative.

for speculative.