Part IV. Mind as Program

The theme of duplicate people—atom-for-atom replicas—has been picked up from fiction by philosophers, most notably by Hilary Putnam, who imagines a planet he calls Twin Earth, where each of us has an exact duplicate or Doppelgänger, to use the German term Putnam favors. Putnam first presented this literally outlandish thought experiment in “The Meaning of ‘Meaning’,” in Keith Gunderson, ed., Language, Mind and Knowledge (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1975, pp. 131–193), where he uses it to establish a surprising new theory of meaning. It is reprinted in the second volume of Putnam’s collected papers, Mind, Language and Reality (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1975). While it seems that almost no philosopher takes Putnam’s argument seriously—that’s what they all say—few can resist trying to say, at length, just where he has gone wrong. A provocative and influential article that exploits Putnam’s fantasy is Jerry Fodor’s intimidatingly entitled “Methodological Solipsism Considered as a Research Strategy in Cognitive Psychology,” published, along with much furious commentary and rebuttal, in The Behavioral and Brain Sciences (vol. 3, no. 1, 1980, pp. 63–73). His comment on Winograd’s SHRDLU, quoted in the Reflections on “Non Serviam,” comes from this article, which is reprinted in Haugeland’s Mind Design.

Prosthetic vision devices for the blind, mentioned in the Reflections on both “Where Am I?” and “What is it Like to be a Bat?”, have been under development for many years, but the best systems currently available are still crude. Most of the research and development has been done in Europe. A brief survey can be found in Gunnar Jansson’s “Human Locomotion Guided by a Matrix of Tactile Point Stimuli,” in G. Gordon, ed., Active Touch (Elmsford, N.Y.: Pergamon Press, 1978, pp. 263–271). The topic has been subjected to philosophical scrutiny by David Lewis in “Veridical Hallucination and Prosthetic Vision,” in the Australasian Journal of Philosophy (vol. 58, no. 3, 1980, pp. 239–249).

Marvin Minsky’s article on telepresenceappeared in Omni in May 1980, pp. 45–52, and contains references to further reading.

When Sanford speaks of the classic experiment with inverting lenses, he is referring to a long history of experiments that began before the turn of the century when G.M. Stratton wore a device for several days that blocked vision in one eye and inverted it in the other. This and more recent experiments are surveyed in R.L. Gregory’s fascinating and beautifully illustrated book, Eye and Brain (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 3rd ed., 1977). Also see Ivo Kohler’s “Experiments with Goggles,” in Scientific American (vol. 206, 1962, pp. 62–72). An up-to-date and very readable book on vision is John R. Frisby’s Seeing: Illusion, Brain, and Mind (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1980).

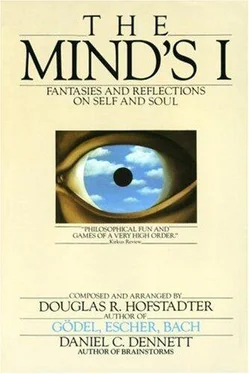

Gödel sentences, self-referential constructions, “strange loops,” and their implications for the theory of the mind are explored in great detail in Hofstadter’s Gödel, Escher, Bach, and with some different twists in Dennett’s “The Abilities of Men and Machines,” in Brainstorms. That Gödel’s Theorem is a bulwark of materialism rather than of mentalism is a thesis forcefully propounded in Judson Webb’s Mechanism, Mentalism, and Metamathematics. A lighter but no less enlightening exploration of such ideas is Patrick Hughes’s and George Brecht’s Vicious Circles and Paradoxes (New York: Doubleday, 1975). C.H. Whitely’s refutation of Lucas’s thesis is found in his article “Minds, Machines and Gödel: A Reply to Mr. Lucas,” published in Philosophy (vol. 37, 1962, p. 61).

Fictional objectshave recently been the focus of considerable attention from philosophers of logic straying into aesthetics. See Terence Parsons, Nonexistent Objects (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1980); David Lewis, “Truth in Fiction,” in American Philosophical Quarterly (vol. 15, 1978, pp. 37–46); Peter van Inwagen, “Creatures of Fiction,” also in American Philosophical Quarterly (vol. 14, 1977, pp. 299–308); Robert Howell, “Fictional Objects,” in D.F. Gustafson and B.L. Tapscott, eds., Body, Mind, and Method: Essays in Honor of Virgil C. Aldrich (Hingham, Mass.: Reidel, 1979); Kendall Walton, “How Remote are Fictional Worlds from the Real World?” in The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism (vol. 37, 1978, pp. 11–23); and the other articles cited in them. Literary dualism, the view that fictions are real, has had hundreds of explorations in fiction. One of the most ingenious and elegant is Borges’s “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius,” in Labyrinths (New York: New Directions, 1964), from which the selections by Borges in The Mind’s I are all drawn.

Part V. Created Selves and Free Will

All of the books on artificial intelligence mentioned earlier have detailed discussions of simulated worldsrather like the world described in “Non Serviam,” except the worlds are much smaller (hard reality has a way of cramping one’s style). See especially the discussion in Raphael’s book, pp. 266–269. The vicissitudes of such “toy worlds” are also discussed by Jerry Fodor in “Tom Swift and his Procedural Grandmother,” in his new collection of essays, RePresentations (Cambridge, Mass.: Bradford Books/MIT Press, 1981), and by Daniel Dennett in “Beyond Belief.” The game of Life and its ramifications are discussed with verve by Martin Gardner in the “Mathematical Games” column of the October, 1970 issue of Scientific American (vol. 223, no. 4, pp. 120–123).

Free willhas of course been debated endlessly in philosophy. An anthology of recent work that provides a good entry into the literature is Ted Honderich, ed., Essays on Freedom of Action (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1973). Two more recent articles that stand out appear together in the Journal of Philosophy (March 1980): Michael Slote’s “Understanding Free Will,” (vol. 77, pp. 136–151) and Susan Wolf’s “Asymmetrical Freedom,” (vol. 77, pp. 151–166). Even philosophers are often prone to lapse into the pessimistic view that no one can ever get anywhere in debates about free will—the issues are interminable and insoluble. This recent work makes that pessimism hard to sustain; perhaps one can begin to see the foundations of a sophisticated new way of conceiving of ourselves both as free and rational agents, choosing and deciding our courses of action, and as entirely physical denizens of a physical environment, as much subject to the “laws of nature” as any plant or inanimate object.

For more commentary on Searle’s “Minds, Brains and Programs,”see the September 1980 issue of The Behavioral and Brain Sciences in which it appeared. Searle’s references are to the books and articles by Weizenbaum, Winograd, Fodor, and Schank and Abelson already mentioned in this chapter, and to Allen Newell and Herbert Simon, “GPS: A Program that Simulates Human Thought,” in E. Feigenbaum and J. Feldman, eds., Computers and Thought (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1963); John McCarthy, “Ascribing Mental Qualities to Machines,” in Ringle’s Philosophical Perspectives in Artificial Intelligence; and Searle’s own papers, “Intentionality and the Use of Language,” in A. Margolit, ed., Meaning and Use (Hingham, Mass.: Reidel, 1979), and “What is an Intentional State?” in Mind (vol. 88, 1979, pp. 74–92).

Читать дальше