Part II. Soul Searching

The Turing testhas been the focus of many articles in philosophy and artificial intelligence. A good recent discussion of the problems it raises is “Psychologism and Behaviorism” by Ned Block, in The Philosophical Review (January 1981, pp. 5–43). Joseph Weizenbaum’s famous ELIZA program, which simulates a psychotherapist with whom one can hold an intimate and therapeutic conversation (typing on a computer terminal), is often discussed as the most dramatic real-life example of a computer “passing” the Turing test. Weizenbaum himself is appalled by the idea, and in Computer Power and Human Reason (San Francisco: Freeman, 1976), he offers trenchant criticism of those who—in his opinion—misuse the Turing test. Kenneth M. Colby’s program PARRY, the simulation of a paranoid patient that “passed” two versions of the Turing test, is described in his “Simulation of Belief Systems,” in Roger C. Schank and Kenneth M. Colby, eds., Computer Models of Thought and Language (San Francisco: Freeman, 1973). The first test, which involved showing transcripts of PARRY’s conversations to experts, was amusingly attacked by Weizenbaum in a letter published in the Communications of the Association for Computing Machinery (vol. 17, no. 9, September 1974, p. 543). Weizenbaum claimed that by Colby’s reasoning, any electric typewriter is a good scientific model of infantile autism: type in a question and it just sits there and hums. No experts on autism could tell transcripts of genuine attempts to communicate with autistic children from such futile typing exercises! The second Turing test experiment responded to that criticism, and is reported in J. F. Heiser, K.M. Colby, W.S. Faught, and K.C. Parkinson, “Can Psychiatrists Distinguish a Computer Simulation of Paranoia from the Real Thing?” in the Journal of Psychiatric Research (vol. 15, 1980, pp. 149–62).

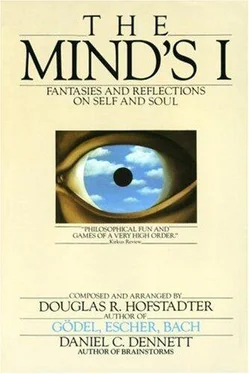

Turing’s “Mathematical Objection” has produced a flurry of literature on the relation between metamathematical limitative theorems and the possibility of mechanical minds. For the appropriate background in logic, see Howard De Long’s A Profile of Mathematical Logic (Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1970). For an expansion of Turing’s objection, see J. R. Lucas’s notorious article “Minds, Machines, and Gödel,” reprinted in the stimulating collection Minds and Machines, edited by Alan Ross Anderson (Engelwood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1964). De Long’s excellent annotated bibliography provides pointers to the furor created by Lucas’s paper. See also Gödel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid by Douglas R. Hofstadter (New York: Basic Books, 1979) and Mechanism, Mentalism, and Metamathematics by Judson Webb (Hingham, Mass.: D. Reidel, 1980).

The continuing debate on extrasensory perceptionand other paranormal phenomena is now followable on a regular basis in the lively quarterly journal The Skeptical Enquirer.

The prospects of ape languagehave been the focus of intensive research and debate in recent years. Jane von Lawick Goodall’s observations in the wild, In the Shadow of Man(Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1971) and early apparent breakthroughs in training laboratory animals to use sign language or other artificial languages by Allen and Beatrice Gardner, David Premack, Roger Fouts, and others led to hundreds of articles and books by scores of researchers and their critics. The experiment with high school students is reported in E.H. Lenneberg, “A Neuropsychological Comparison between Man, Chimpanzee and Monkey,” Neuropsychologia (vol. 13, 1975, p. 125). Recently Herbert Terrace, in Nim: A Chimpanzee Who Learned Sign Language (New York: Knopf, 1979), managed to throw a decidedly wet blanket on this enthusiasm with his detailed analysis of the failures of most of this research, including his own efforts with his chimpanzee, Nim Chimpsky, but the other side will surely fight back in forthcoming articles and books. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences (BBS) of December 1978 is devoted to these issues and contains major articles by Donald Griffin, author of The Question of Animal Awareness (New York: Rockefeller Press, 1976), by David Premack and Guy Woodruff, and by Duane Rumbaugh, Sue Savage-Rumbaugh, and Sally Boysen. Accompanying these articles are a host of critical commentaries by leading researchers in linguistics, animal behavior, psychology and philosophy, and replies by the authors. In BBS, a new interdisciplinary journal, every article is followed by dozens of commentaries by other experts and a reply by the author. In a field as yeasty and controversial as cognitive science, this is proving to be a valuable format for introducing the disciplines to each other. Many other BBS articles in addition to those mentioned here provide excellent entry points into current research.

Although there is clearly a link of great importance between consciousness and the capacity to use language, it is important to keep these issues separate. Self-consciousness in animals has been studied experimentally. In an interesting series of experiments, Gordon Gallup established that chimpanzees can come to recognize themselves in mirrors—and they recognize themselves as themselves too, as he demonstrated by putting dabs of paint on their foreheads while they slept. When they saw themselves in the mirrors, they immediately reached up to touch their foreheads and then examined their fingers. See Gordon G. Gallup, Jr., “Self-recognition in Primates: A Comparative Approach to the Bidirection Properties of Consciousness,” American Psychologist (vol. 32, (5), 1977, pp. 329–338). For a recent exchange of views on the role of language in human consciousness and the study of human thinking, see Richard Nisbett and Timothy De Camp Wilson, “Telling More Than We Know: Verbal Reports on Mental Processes,” Psychological Review (vol. 84, (3), 1977, pp. 321–359) and K. Anders Ericsson and Herbert Simon, “Verbal Reports as Data,” Psychological Review (vol. 87, (3), May 1980, pp. 215–250).

Many robots like the Mark III Beast have been built over the years. One at Johns Hopkins University was in fact called the Hopkins Beast. For a brief illustrated review of the history of robots and an introduction to current work on robots and artificial intelligence, see Bertram Raphael, The Thinking Computer: Mind Inside Matter (San Francisco: Freeman, 1976). Other recent introductions to the field of AI are Patrick Winston’s Artificial Intelligence (Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1977), Philip C. Jackson’s Introduction to Artificial Intelligence (Princeton, N.J.: Petrocelli Books, 1975), and Nils Nilsson’s Principles of Articial Intelligence (Menlo Park, Ca.: Tioga, 1980). Margaret Boden’s Artificial Intelligence and Natural Man (New York: Basic Books, 1979) is a fine introduction to AI from a philosopher’s point of view. A new anthology on the conceptual issues confronted by artificial intelligence is John Haugeland, ed., Mind Design: Philosophy, Psychology, Artificial Intelligence (Montgomery, Vt.: Bradford, 1981), and an earlier collection is Martin Ringle, ed., Philosophical Perspectives on Artificial Intelligence (Atlantic Highlands, N.J.: Humanities Press, 1979). Other good collections on these issues are C. Wade Savage, ed., Perception and Cognition: Issues in the Foundations of Psychology (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1978) and Donald E. Norman, ed., Perspectives on Cognitive Science (Norwood, N.J.: Ablex, 1980).

Читать дальше