That symbolization is radically and generically different from signification is confirmable in various ways. There is the sudden discovery of the symbol in the history of deaf-mutes, such as the well-known incident in which Helen Keller, who had “understood” words but only as signs awoke to the extraordinary circumstance that the word water meant, denoted, the substance water.* There are the genetic studies of normal children, as for example the observation of Schachtel, who speaks of the “autonomous object interest” of young children as being altogether different from the earlier need-gratification interest.† Symbolization can be approached genetically, as the proper subject of an empirical psychology, or it can be set forth phenomenologically, as a meaning structure with certain irreducible terms and relations.

Let us first take notice of the gross elements of the symbol meaning situation and later of the interrelations which exist between them.

THE SECOND ORGANISM AND THE RELATION OF INTERSUBJECTIVITY

What happens, then, when a sign becomes a symbol; when a sound, a vocable, which had served as a stimulus in the causal nexus of organism-in-an-environment, is suddenly discovered to mean something in the sense of denoting it?

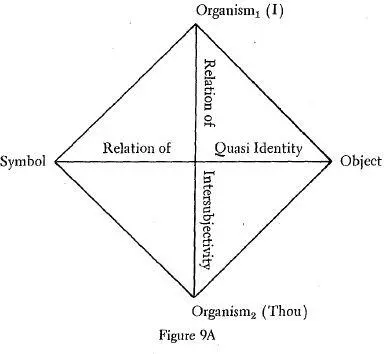

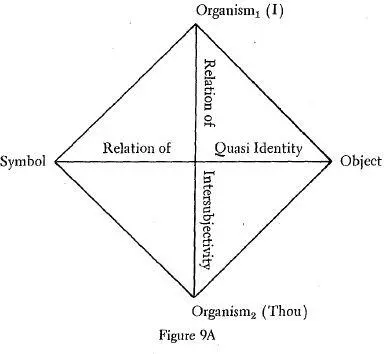

It will be recalled that the relation of signification is a triadic one of sign-organism-object (Figure 9). This schema holds true for any significatory meaning situation. It is true of a dog responding to a buzzer by salivation; it is true of a polar bear responding to the sound of splitting ice; it is true of a man responding to a telephone bell;* it is true of little Helen Keller responding to the word water by fetching water. The essential requirement of signification is that there be an organism in an environment capable of learning by effecting an electrocolloidal change in the central nervous system and as a consequence responding to a stimulus in a biologically adaptive fashion.†

It is important to realize that whereas signification often occurs between two or more organisms, it is not essential that it should, and that generically the sort of response is the same whether one or more organisms are involved. The action of a dog in responding intelligently to the bark or feint of another dog — Mead’s “conversation of gesture”—is generically the same sort of meaning relation as that in which a solitary polar bear responds to the sound of splitting ice. It is the environment to which the organism responds in a biologically adaptive fashion, and the mode of response is the same whether the environment consist of other organisms or of inorganic nature.

Only a moment’s reflection is needed to realize that the minimal requirement of symbolization is quite different. By the very nature of symbolic meaning, there must be two “ organisms” in the meaning relation, one who gives the name and one for whom the name becomes meaningful. The very essence of symbolization is an entering into a mutuality toward that which is symbolized. The very condition of my conceiving the object before me under the auspices of a symbol is that you name it for me or I name it for you. The act of symbolization requires another besides the hearer; it requires a namer. Without the presence of another, symbolization cannot conceivably occur because there is no one from whom the word can be received as meaningful. The irreducible condition of every act of symbolization is the rendering intelligible; that is to say, the formulation of experience for a real or an implied someone else.

The presence of the two organisms is not merely a genetic requirement, a sine qua non of symbolization; it is rather its enduring condition, its indispensable climate. Every act of symbolization, a naming, forming an hypothesis, creating a line of poetry, perhaps even thinking, implies another as a co-conceiver,* a co-celebrant of the thing which is symbolized. Symbolization is an exercise in intersubjectivity.

A new and indefeasible relation has come into being between the two organisms in virtue of which they are related not merely as one organism responding to another but as namer and hearer, an I and a Thou. Mead’s two dogs quarreling over a bone exist in a conversation of gesture, a sequential order of gesture and countergesture. But a namer and a hearer of the name exist in a mutuality of understanding toward that which is symbolized. Here the terminology of object science falls short. One must use such words as mutuality or intersubjectivity, however unsatisfactory they may be. But whatever we choose to call it, the fact remains that there has occurred a sudden cointending of the object under the auspices of the symbol, a relation which of its very nature cannot be construed in causal language.†

Is it possible, then, that an unprejudiced semiotic may throw some light on the interpersonal relation, the I-Thou of Buber, the intersubjectivity of Marcel? As things stand now, the empirical mind can make very little of this entity “intersubjectivity,” and the behaviorist nothing at all. Like other existential themes, it seems very much in the air. Yet an empirical approach to the genesis of symbolization is bound to reveal it as a very real, if mysterious, relation. Perhaps the contribution of a new semiotic will be that intersubjectivity is by no means a reducible, or an imaginary, phenomenon but is a very real and pervasive bond and one mediated by a sensible symbol and a sensible object which is symbolized.*

We may therefore revise the sign triad as the symbol tetrad (see Fig. 9A).

The “organisms” no longer exist exclusively in a causal nexus but are united by a new and noncausal bond, the relation of intersubjectivity.

But a new relation has also arisen between the object and its symbol. What is the nature of the “imputed relation of identity”?

THE INTENTIONAL RELATION OF IDENTITY

Mead said that a vocal gesture (sign) becomes a symbol when the individual responds to his own stimulus in the same way as other

people respond. Yet one cannot fail to realize that something is amiss in construing as a response Helen Keller’s revelation that this is water. And certainly it misses the peculiar representative function of language to declare that, when I ask you to do something, I also arouse in myself the same tendency to do it.

What, then, is changed in the semiotic relation by Helen Keller’s inkling that this is water? Physically, the elements are the same as before. There is Helen; there is Miss Sullivan; there is the water flowing over one hand, and there is the word spelled out in the other. Yet something of very great moment has occurred. Not only does she have the sense of a revelation, so that all at once the whole world is open to her, not only does she experience a very great happiness, a joy which is quite different from her previous need-satisfactions (see Schachtel’s “autonomous object interest” above), but immediately after discovering what the water is, she must then know what everything else is.

The critical question may now be raised. In discovering the peculiar denotative function of the symbol, has Helen only succeeded in opening Pandora’s box of all our semantical ills of “identification,” or has she hit upon the indispensable condition of our knowing anything at all, perhaps even of consciousness itself?* Is her joy a “hallucinatory need-satisfaction,” an atavism of primitive word-magic; or is it a purely cognitive joy oriented toward being and its validation through the symbol?

It comes down to the mysterious naming act, this is water (the word spelled out in her hand). Here, of course, is where the trouble starts. For clearly, as the semanticists never tire of telling us, the word is not water. You cannot eat the word oyster, Chase assures us; but then not even the most superstitious totemistic tribesman would try to.† Yet the semanticists themselves are the best witnesses of the emergence of an extraordinary relation — which they deplore as the major calamity of the human race — the relation of an imputed identity between word and thing. Undoubtedly the semanticists have performed a service in calling attention to the human penchant for word magic, for reifying meanings by simply applying words to them. Gabriel Marcel frequently speaks of the same tendency of “simulacrum” formation, by which meanings become hardened and impenetrable to thought. Yet one wonders if it might not be more useful to investigate this imputed identity for what part it might play in human knowing, rather than simply deplore it — which is after all an odd pursuit for a “scientific empiricist.”

Читать дальше