Second, the theorist may elect to remain altogether on the cogito side of the mind-body split. He may view the problem simply as a semantico-logical one, stipulating a natural law as a “syntactical rule,” a free convention for the manipulation of symbols, refusing to deal with the problems of knowledge and induction and intersubjectivity (Carnap).* Or he may adopt the operationalism of Bridgman, who is frank to admit the consequence of solipsism: “…it is obvious that I can never get outside myself…there is no such thing as a public consciousness…in the last analysis science is only my private science.” In this case, the antinomy is overt: a practicing scientist who reports his findings in journals and his theories in books — and who denies the possibility of a public realm of intersubjectivity. A kindred approach is a neo-Kantian one, which seeks scientific validity entirely within the forms and categories of consciousness: “The validity of the physical concept does not rest upon its content of real elements of existence, such as can be directly pointed out, but upon the strictness of connection, which makes it possible” (Cassirer).

(3) Comment. Einstein once wrote, “If you want to find out anything from the theoretical physicists about the methods they use, I advise you to stick closely to one principle: don’t listen to their words, fix your attention on their deeds.”

Whitehead once remarked that it was a matter for astonishment that while scientists have succeeded in learning a great deal about the world in the past two hundred years, philosophers of science seem equally determined to deny that such knowledge is possible.

Both men allude to the antinomy which the functional method of the sciences encounters when it tries to grasp itself as a phenomenon among other phenomena in the world. The antinomy has been noticed often enough but it is usually attributed to the bad faith or bad philosophizing of the theorist. It seems to be a case, however, of too much good faith rather than too little — that is, an uncritical acceptance of the scientific method of physics as a total organon of reality. The antinomy has come to pass precisely because of the faithfulness and rigor with which the theorist tries to grasp the scientific enterprise in particular, assertory activity in general, by his superb instrument, the functional method of the sciences.

The ineluctable reality upon which the scientific method founders and splits into an antinomy is nothing else than the central act of science, “sciencing,” the assertions of science. From the primitive observation to the most exact mathematical deduction, science is a tissue of assertions. It is ironical but perhaps not unfitting that science, undertaken as a total organon of reality, should break down not at the microcosmic or macrocosmic limits of the universe but in the attempt to grasp itself. Heisenberg’s uncertainty relations seem to be a material difficulty resulting from an interference of measuring instrument with particle to be measured.* But the antinomy into which the scientific method falls in treating as-sertory behavior is a formal methodological impasse. It lies beyond the power of the functional method to grasp the scientific, the mythic, the linguistic assertion as such. It will succeed in grasping itself according to its mode — as a functional space-time linkage — but in so doing it must overlook its most important characteristic, that science is an assertory phenomenon, a real phenomenon but not a causal space-time event. Science may seek to understand itself as a social instrumentality or as an intracultural activity, and to a degree no doubt correctly so; but it must remain silent in the face of the true-or-false claim, S is P, considered as such.

Here, as in the other antinomies, it is the assertory act itself which is refractory to the scientific method. Since an assertion — mythic, linguistic, mathematical — is an immaterial act in virtue of which two elements are paired or identified, and since the scientific method requires that elements be ordered serially, according to dependent functional ratios, the two are not commensurate. The corpus of scientific knowledge ascending in a continuum from inorganic energy exchanges to organic responses is not in principle coterminous with assertory behavior. To speak of culture as an “emergent” or a “superorganic level” is only to erect a semantical bridge across the abyss, when the need is to explore the abyss, not to ignore it.

Different as are the various scientific philosophies mentioned above, they share one conviction about the subject matter of science and it is this conviction which gives rise to the antinomy. It is the antirealist and antimetaphysical dogma that there is no lawful reality to be known apart from the activity of the knower. This tenet is usually expressed in an exaggerated language: “Knowledge conceived in the fashion of an infallible grasp of final truths without the mediation of overt organic activity is not something which modern science supplies.” What should be pointed out, however, is that it is not the claim to “infallible knowledge” which gives scandal to positivist philosophers of science; it is the claim to any valid knowledge whatsoever, however modest the claim of the knower. A realist would be the first to admit, would in fact insist upon, “the mediation of overt organic activity” in the knowing act. But this is not the real point at issue. The issue is the validity of knowledge and the providing for this validity in one’s scientific world view. The difficulty is that knowledge entails assertions and assertions are beyond the grasp of the functional method.*

THE SOURCE OF THE ANTINOMY

The general source of the antinomy is not to be found, as is sometimes alleged, in the nature of the subject, man, the culture member who practices science but needs myths. Such an anthropology is in the last analysis incoherent because it requires two sorts of men, scientists who observe and tell the truth, culture members who respond and have mythic needs.

The source is rather to be found in the structure and limitations of the scientific method itself. For the antinomy comes about at that very moment when that sort of activity of which the scientific method is a mode, assertory activity, enters the scientific situation, not as the customary activity of the scientist, but as a phenomenon under investigation.

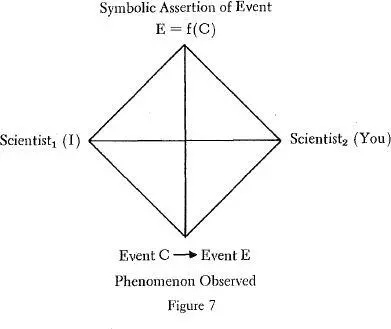

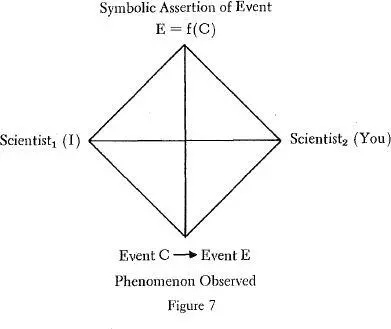

The basic structure of the scientific situation is an intersubjective confrontation of a world event and its construing by a symbolic assertion. The general structure of any symbolic cognition is tetradic, as diagrammed in Figure 7, as contrasted with the triadic structure of significatory meaning (sign-organism-thing).

What should be noticed is that there is a difference between the sort of thing we, Scientist 1and Scientist 2, understand the world to be (a nexus of secondary causes, event C → event E), and the assertion by which we express this understanding (E =f (C)). One is a dynamic succession of energy states, the other is an assertion, an immaterial act by which two entia rationis are brought into a relation of intentional identity. Both these elements, world event and symbolic assertion, are provided for in the scientific method but it is a topical provision such that a symbolic assertion, S is P, E =f (C) , is admitted as the sort of activity which takes place between scientists but is not admitted as a phenomenon under observation. A scientific assertion is received only as a true-or-false claim, which is then proved or disproved by examining the world event to which it refers. The symbolic assertion cannot itself be examined as a world event unless it be construed as such, as a material event of energy exchanges, in which case its assertory character must be denied.

Читать дальше