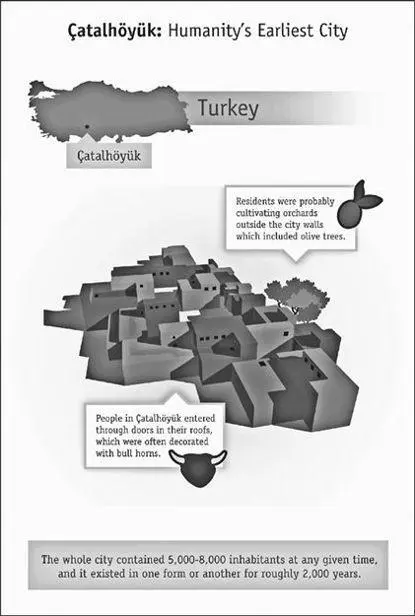

One of the great debates among anthropologists is whether urban life or agricultural life came first. Though we may never know the answer—and it may have varied from region to region—most anthropologists today agree that cities like Caral and Çatalhöyük would have required people to develop highly efficient agriculture. After all, farming is only necessary when there are hundreds or even thousands of hungry mouths to feed in one permanent location. Did the city therefore predate the farm? Tantalizing evidence from a southern Turkish site called Göbekli Tepe, dating from 10,000 BCE—a fascinating circular formation of monuments covered in bizarre human-animal imagery—suggests that the very earliest urban formations were built before evidence of agriculture. Still, it’s possible that humans’ first efforts at crop cultivation would be impossible to distinguish from wild plants, meaning the people who visited Göbekli Tepe might have had small farms that we simply can’t recognize from their remains. Debates aside, what’s certain is that by the time people were living in the extremely ancient cities of Caral and Çatalhöyük, farming was the main occupation of most urbanites. Cities cannot exist without agriculture.

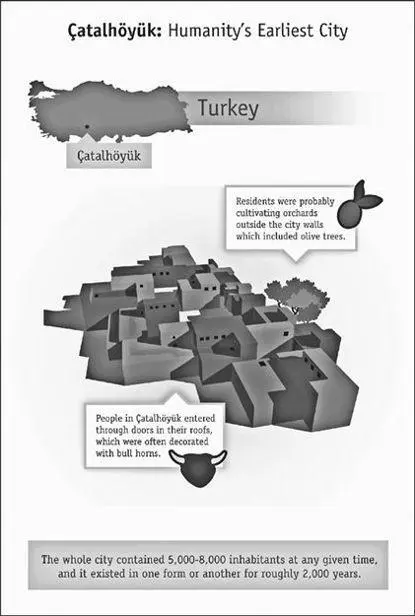

An artist’s conception of what the ancient city of Çatalhöyük might have looked like. There were no streets, and people entered their homes through holes in the roofs. (illustration credit ill.10)

(Click here to see a larger image.)

Cities didn’t just change the environment with agriculture; they changed humanity, too. Stanford University anthropologist Ian Hodder, who has led excavations at Çatalhöyük since the early 1990s, believes that cities “socialize” people. Their routines are transformed by what he calls “bodily repetition of practices and routines in the house,” as well as the “construction of memories.” He writes about one house in Çatalhöyük whose residents rebuilt the structure six times over a couple of centuries, each time with exactly the same layout. Like their neighbors, these people shared a religious tradition of burying the bones of their ancestors in the floor of the house. As time passed, the house became more than just a dwelling. It was a monument to previous versions of the house, to the family, and to the city itself. This is a useful way to think about cities in general, and helps illuminate why we attach so much significance to preserving ancient structures in our modern cities. Our cities are monuments to our shared history. Though the bones of our ancestors aren’t literally built into the floors of our homes anymore, they remain there in a symbolic sense. That ineffable megapolisomancy that gives cities their allure comes from the way they are constructed of memories as much as they are constructed from brick and steel.

Anthropologist Elizabeth Stone has been excavating ancient cities in the Mesopotamian region, especially Turkey and Iraq, since the early 1980s. When I asked her why some cities manage to survive for thousands of years, she cautioned me that cities don’t ever remain the same over time; they have broken histories, collapsing and rising again. Ancient cities, for example, were organized in a way dramatically unlike cities of today. “If you look at pictures of Baghdad today, you see different districts that are segregated by class. It’s so fundamental that it’s visible from space,” she said. But if you look at the layout of ancient Pompeii, it’s impossible to say where the rich and the poor lived. There is variability between neighborhoods, but there are no visible differences in wealth. As she’s mapped Mesopotamian Era cities, Stone has been struck by how little variability there is in the size of houses. Everybody seems to have homes that are roughly the same dimensions, though some might have more rooms than others.

The differences between ancient and medieval cities are just as stark. The imperialist Rome of antiquity wasn’t the same as the Church-dominated Rome of the Middle Ages. The former glory of the ancient world was reborn as a new city for the medieval world. Medieval city growth moved slowly, often funded by the aristocracy or the church. But starting in the nineteenth century, industrialization pushed city growth into the hands of wealthy entrepreneurs and developers, whose greatest monuments became skyscrapers devoted to various corporate headquarters. This era also witnessed a steep rise in urban populations, culminating in our majority urban population today. And now it’s become a completely different city again. People have always been drawn to Rome because of its dramatic history, but the urban experience during each stage of its life was notably transformed.

Long-lived cities survive by going through periods of collapse and rejuvenation. It’s possible that cities tend to collapse when people have less social and economic mobility. “People at the bottom may retreat into the countryside and leave the sphere that’s controlled by the city,” Stone speculated. As soon as there is more opportunity in the city, peasants return and try to climb the social ladder again. Most cities that last for more than a few hundred years are located at the heart of shifting empires, like Istanbul (formerly Constantinople) or Mexico City (formerly Tenochtitlán). Both cities have been inhabited for centuries, but by peoples from successive, often adversarial political groups. Their fates rise and fall with the empires that claim them. Cities may be built on memory, but they are also processes, always changing.

Longevity isn’t the only measure of a city’s success, however. As Harvard economist Edward Glaeser puts it in his book Triumph of the City: How Our Greatest Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier, and Happier:

Among cities, failures seem similar while successes feel unique…. Successful cities always have a wealth of human energy that expresses itself in different ways and defines its own idiosyncratic space.

Modern cities survive by offering people a space where they can form social groups that would be impossible outside them. Kostof calls cities “cumulative, generational artifacts that harbor our values as a community and provide us with the setting where we can learn to live together.” The city community’s “values” are part of the urban structure itself. This helps explain why some cities remain politically distinct from their countries, their cultures proving stronger than the culture of their nations. In the last century, West Berlin and Hong Kong found themselves in this situation. Both cities had strong ties to other nations and urban areas, and used those ties to remain relatively democratic cities devoted to capitalist trade, despite being located inside and alongside powerful communist nations. Other examples include cities like New York and Budapest, whose citizens have often defined themselves by being at odds with the countries that contain them. Cities socialize citizens into certain habits of mind, and these can be hard to break. In fact, sometimes a city breaks with its nation rather than breaking away from its own social norms.

Case Study: San Francisco as a City of Tomorrow

How can we ensure that tomorrow’s cities will harbor thriving communities that don’t decay into insignificance like Detroit or disappear into the fog of history like Çatalhöyük? We need to incorporate mutability into urban design. But as we face the future, that mutability must also include ways of building sustainability into the very structure of our cities. Urban geographer Richard Walker believes the San Francisco Bay Area provides a useful template for how that could happen. In his book about San Francisco, The Country in the City , he explains how the Bay Area’s green spaces are as much constructions as the houses and buildings. The region’s designers often built verdant parks on top of barren dunes and scrub, including both “country” and “city” in their plans for how they would convert the wild lands of Northern California into an urban space. The results are visible everywhere in the Bay Area. To get from the BART commuter-train station to Walker’s Berkeley home, I followed a winding path through several public parks full of play equipment and flower beds. Along the way, I passed more bicyclists, pedestrians, and green spaces than I did cars.

Читать дальше

![Аннали Ньюиц - Автономность [litres]](/books/424681/annali-nyuic-avtonomnost-litres-thumb.webp)