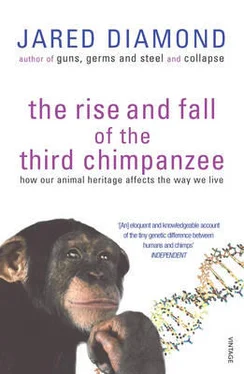

Jared Diamond - The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jared Diamond - The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1991, ISBN: 1991, Издательство: RADIUS, Жанр: Биология, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee

- Автор:

- Издательство:RADIUS

- Жанр:

- Год:1991

- ISBN:0-09-174268-4

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

For eastern New Guinea, the myth of an empty interior was shattered on 26 May 1930, when two Australian miners, Michael Leahy and Michael Dwyer, scaled the crest of the Bismarck Mountains in search of gold, looked down at night on the valley beyond, and were alarmed to see countless dots of light: the cooking fires of thousands of people. For western New Guinea, the myth ended with Archbold's second survey flight on 23 June 1938. After hours of flying over jungle with few signs of humans, Archbold was astonished to spot the Grand Valley, looking like Holland: a cleared landscape devoid of jungle, neatly divided into small fields outlined by irrigation ditches, and with scattered hamlets. It took six more weeks before Archbold could establish camps at the nearest lake and river where his seaplane could land, and before patrols from those camps could reach the Grand Valley to make first contact with its inhabitants. That is why the outside world did not know of the Grand Valley till 1938.

Why did the valley's inhabitants, now referred to as the Dani people, not know of the outside world?

Part of the reason, of course, is the same logistic problems that faced the Kremer Expedition on its march inland, but in reverse. Yet those problems would be minor in areas of the world with gentler terrain and more wild foods than New Guinea, and they do not explain why all other human societies in the world also used to live in relative isolation. Instead, at this point we have to remind ourselves of a modern perspective that we take for granted. Our perspective did not apply to New Guinea until very recently, and it did not apply anywhere in the world 10,000 years ago. Recall that the whole globe is now divided into political states, whose citizens enjoy more or less freedom to travel within the boundaries of their state and to visit other states. Anyone with the time, money, and desire can visit almost any country except for a few xenophobic exceptions, such as Albania and North Korea. As a result, people and goods have diffused around the globe, and many items such as Coca-cola are now available on every continent. I recall with embarrassment my visit in 1976 to a Pacific island called Rennell, whose isolated location, vertical sea cliffs without beaches, and fissured coral landscape had preserved its Polynesian culture unchanged until recently. Setting out at dawn from the coast, I plodded through jungle with not a trace of humans. When in the late afternoon I finally heard a woman's voice ahead and glimpsed a small hut, my head whirled with fantasies of the beautiful, unspoilt, grass-skirted, bare-breasted Polynesian maiden who awaited me at this remote site on this remote island. It was bad enough that the lady proved to be fat and with her husband. What humiliated my self-image as intrepid explorer was the 'University of Wisconsin' sweatshirt that she wore. In contrast, for all but the last 10,000 years of human history, unfettered travel was impossible, and diffusion of sweatshirts was very limited. Each village or band constituted a political unit, living in a perpetually shifting state of wars, truces, alliances, and trade with neighbouring groups. New Guinea Highlanders spent their entire lives within twenty miles of their birthplace. They might occasionally enter lands bordering their village lands by stealth during a war raid, or by permission during a truce, but they had no social framework for travel beyond immediately neighbouring lands. The notion of tolerating unrelated strangers was as unthinkable as the notion that any such stranger would dare appear.

Even today, the legacy of this no-trespassing mentality persists in many parts of the world. Whenever I go bird-watching in New Guinea, I take pains to stop at the nearest village to request permission to bird-watch on that village's land or rivers. On two occasions when I neglected that precaution (or asked permission at the wrong village) and proceeded to boat up the river, I found the river barred on my return by canoes of stone-throwing villagers, furious that I had violated their territory. When I was living among Elopi tribespeople in western New Guinea and wanted to cross the territory of the neighbouring Fayu tribe to reach a nearby mountain, the Elopis explained to me matter-of-factly that the Fayus would kill me if I tried. From a New Guinean perspective, it seemed perfectly natural and self-explanatory. Of course the Fayus will kill any trespasser; you surely do not think they are so stupid that they would admit strangers to their territory? Strangers would just hunt their game animals, molest their women, introduce diseases, and reconnoitre the terrain in order to stage a raid later.

While most pre-contact peoples had trade relations with their neighbours, many thought they were the only humans in existence. Perhaps the smoke of fires on the horizon, or an empty canoe floating past down a river, did prove the existence of other people. But to venture out of one's territory to meet those humans, even if they lived only a few miles away, was equivalent to suicide. As one New Guinea highlander recalled his life before first arrival of whites in 1930, 'We had not seen far places. We knew only this side of the mountains. And we thought that we were the only living people.

Such isolation bred great genetic diversity. Each valley in New Guinea has not only its own language and culture, but also its own genetic abnormalities and local diseases. The first valley where I worked was the home of the Fore people, famous to science for their unique affliction with a fatal viral disease called kuru or laughing sickness, which accounted for over half of all deaths (especially among women) and left men outnumbering women three-to-one in some Fore villages. At Karimui, sixty miles to the west of the Fore area, kuru is completely unknown, and the people are instead affected with the world's highest incidence of leprosy. Still other tribes are unique in their high frequency of deaf mutes, or of male pseudo-hermaphrodites lacking a penis, or of premature aging, or of delayed puberty.

Today we can picture areas of the globe that we have not visited, from films and television. We can read about them in books. English dictionaries exist for all the world's major languages, and most villages speaking minor languages contain individuals who have learned one of the world's major languages. For example, missionary linguists have studied literally hundreds of New Guinea and South American Indian languages in recent decades, and I have found some inhabitant speaking either Indonesian or Neo-Melanesian in every New Guinea village that I have visited, no matter how remote. Linguistic barriers no longer impede the worldwide flow of information. Almost every village in the world today has thereby obtained fairly direct accounts of the outside world and has yielded fairly direct accounts of itself.

In contrast, pre-contact peoples had no way to picture the outside world, or to learn about it directly. Information instead arrived via long chains of languages, with accuracy lost at each step—as in the children's game called 'telephone' or 'Chinese whispers', where one child in a circle whispers a message to the next child, who in turn whispers it to her neighbour, until by the time the message is whispered back to the first child its meaning has become changed beyond recognition. As a result, New Guinea highlanders had no concept of the ocean a hundred miles distant, and knew nothing about the white men who had been prowling their coasts for several centuries. When highlanders tried to figure out why the first arriving white men wore trousers and belts, one theory was that the clothes served to conceal an enormously long penis coiled around the waist. Some Dani believed that a neighbouring group of New Guineans munched grass and had their hands joined behind their back.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.