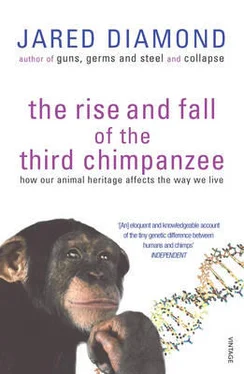

Jared Diamond - The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jared Diamond - The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1991, ISBN: 1991, Издательство: RADIUS, Жанр: Биология, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee

- Автор:

- Издательство:RADIUS

- Жанр:

- Год:1991

- ISBN:0-09-174268-4

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

On 4 August 1938, an exploratory biological expedition from the American Museum of Natural History made a discovery that hastened towards its end a long phase of human history. That was the date on which the advance patrol of the Third Archbold Expedition (named after its leader, Richard Archbold) became the first outsiders to enter the Grand Valley of the Balim River, in the supposedly uninhabited interior of western New Guinea. To everyone's astonishment, the Grand Valley proved to be densely populated—by 50,000 Papuans, living in the Stone Age, previously unknown to the rest of humanity and themselves unaware of others' existence. In search of undiscovered birds and mammals, Archbold had found an undiscovered human society. To appreciate the significance of Archbold's finding, we need to understand the phenomenon of'first contact'. As I mentioned on page 198, most animal species occupy a geographic range confined to a small fraction of the Earth's surface. Of those species occurring on several continents (such as lions and grizzly bears), it is not the case that individuals from one continent visit one another. Instead, each continent, and usually each small part of a continent, has its own distinctive population, in contact with close neighbours but not with distant members of the same species. (Migratory songbirds constitute an apparently glaring exception. But while they do commute seasonally between continents, it is only along a traditional path, and both the summer breeding range and the winter non-breeding range of a given population tend to be quite circumscribed.) This geographic fidelity of animals is reflected in the geographic variability that I discussed in Chapter Six. Populations of the same species in different geographic areas tend to evolve into different-looking subspecies, because most breeding remains within the same population. For example, no gorilla of the East African lowland subspecies has ever turned up in West Africa or vice versa, though the eastern and western subspecies look, sufficiently different that biologists could recognize a wanderer if there were any.

In these respects, we humans have been typical animals throughout most of our evolutionary history. Like other animals, each human population is genetically moulded to its area's climate and diseases, but human populations are also impeded from freely mixing by linguistic and cultural barriers far stronger than in other animals. As mentioned in Chapter Six, an anthropologist can identify roughly where a person originates from the person's naked appearance, and a linguist or student of dress styles can pinpoint origins much more closely. That is testimony to how sedentary human populations have been.

While we think of ourselves as travellers, we were quite the opposite throughout several million years of human evolution. Every human group was ignorant of the world beyond its own lands and those of its immediate neighbours. Only in recent millenia did changes in political organization and technology permit some people routinely to travel afar, to encounter distant peoples, and to learn first-hand about places and peoples that they had not personally visited. This process accelerated with Columbus's voyage of 1492, until today there remain only a few tribes in New Guinea and South America still awaiting first contact with remote outsiders. The Archbold Expedition's entry into the Grand Valley will be remembered as one of the last first contacts of a large human population. It was thus a landmark in the process by which humanity became transformed from thousands of tiny societies, collectively occupying only a fraction of the globe, to world conquerors with world knowledge. How could such a numerous people as the Grand Valley's 50,000 Papuans remain completely unknown to outsiders until 1938? How could those Papuans in turn remain completely ignorant of the outside world? How did first contact change human societies? I shall argue that this World before first contact—a world that is finally ending within our own generation—holds a key to the origins of human cultural diversity. As World conquerors, our species now numbers over five billion, compared to the mere ten million people who existed before the advent of agriculture. Ironically, though, our cultural diversity has plunged even as our numbers have soared.

To anyone who has not been to New Guinea, the long concealment of 50,000 people there seems incomprehensible. After all, the Grand Valley lies only 115 miles from both New Guinea's north coast and its south coast. Europeans discovered New Guinea in 1526, Dutch missionaries took up residence in 1852, and European colonial governments were established in 1884. Why did it take another fifty-four years to find the Grand Valley?

The answers—terrain, food, and porters—become obvious as soon as one sets foot in New Guinea and tries to walk away from an established trail. Swamps in the lowlands, endless series of knife-edge ridges in the mountains, and jungle that covers everything reduce one's progress to a few miles per day under the best conditions. On my 1983 expedition into the Kumawa Mountains, it took me and a team of twelve New Guineans two weeks to penetrate seven miles inland. Yet we had it easy compared to the British Ornithologists' Union Jubilee Expedition. On 4 January 1910 they landed on New Guinea's coast and set off for the snowcapped mountains that they could see only a hundred miles inland. On 12 February 1911 they finally gave up and turned back, having covered less than half the distance (forty-five miles) in those thirteen months.

Compounding those terrain problems is the impossibility of living off the land, because of New Guinea's lack of big game animals. In lowland jungle the staple of New Guineans is a tree called the sago palm, whose pith yields a substance with the consistency of rubber and the flavour of vomit. However, not even New Guineans can find enough wild foods to survive in the mountains. This problem was illustrated by a horrible sight on which the British explorer Alexander Wollaston stumbled while descending a New Guinea jungle trail: the bodies of thirty recently dead New Guineans and two dying children, who had starved while trying to return from the lowlands to their mountain gardens without carrying enough provisions.

The paucity of wild foods in the jungle compels explorers going through uninhabited areas, or unable to count on obtaining food from native gardens, to bring their own rations. A porter can carry forty pounds, the weight of the food necessary to feed himself for about fourteen days. Thus, until the advent of planes made airdrops possible, all New Guinea expeditions that penetrated more than seven days' walk from the coast (fourteen days' round trip) did so by having teams of porters going back and forth, building up food depots inland. Here is a typical plan: fifty porters start from the coast with 700 man-days of food, deposit 200 man-days' food five days inland, and return in another five days to the coast, having consumed the remaining 500 man-days' food (fifty men times ten days) in the process. Then fifteen porters march to that first depot, pick up the cached 200 man-days' food, deposit fifty man-days' food a further five days' march inland, and return to the first depot (reprovisioned in the meantime), having consumed the remaining 150 man-days' food in the process. Then. . The expedition that came closest to discovering the Grand Valley before Archbold, the 1921-22 Kremer Expedition, used 800 porters, 200 tons of food, and ten months of relaying to get four explorers inland to just beyond the Grand Valley. Unfortunately for Kremer, his route happened to pass a few miles west of the valley, whose existence he did not suspect because of intervening ridges and jungle.

Apart from these physical difficulties, the interior of New Guinea seemed to hold no attractions for missionaries or colonial governments, because it was believed to be virtually uninhabited. European explorers landing on the coast or rivers discovered many tribes in the lowlands living off sago and fish, but few people eking out an existence in the steep foothills. From either the north or south coast, the snow-capped Central Cordillera that forms New Guinea's backbone presents steep faces. It was assumed that the northern and southern faces meet in a ridge. What remained invisible from the coasts was the existence of broad inter-montane valleys, hidden behind those faces and suitable for agriculture.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.