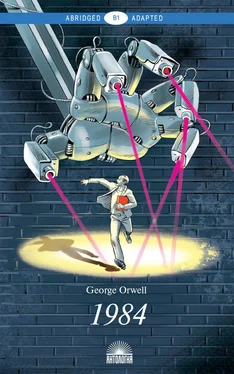

Winston looked at the page. He discovered that while he had been thinking he had also been writing. And it was no longer the same handwriting as before. In large capitals he had written:

DOWN WITH BIG BROTHER

DOWN WITH BIG BROTHER

DOWN WITH BIG BROTHER

DOWN WITH BIG BROTHER

DOWN WITH BIG BROTHER

over and over again.

He was afraid. The writing of those words was not more dangerous than opening the diary, but for a moment he wanted to tear out the pages and never touch the diary again.

He did not do so, however, because he knew that it was useless. Whether he wrote DOWN WITH BIG BROTHER, or whether he didn't, made no difference. Whether he continued writing the diary, or whether he did not, made no difference. The Thought Police would arrest him just the same. He had committed a thoughtcrime. You could not hide it for ever. Sooner or later they would arrest you.

It was always at night – the arrests happened at night. The hand shaking your shoulder, the lights, the ring of faces round the bed. There was rarely a trial or a report of the arrest. People just disappeared, always during the night. Your name was removed from the registers, you were forgotten. You were vapourized, that was the usual word.

For a moment he was frightened to death. He began writing quickly: they'll shoot me I don't care they'll shoot me in the back of the neck I don't care down with big brother they always shoot you in the back of the neck I don't care down with big brother…

He sat back in his chair, slightly ashamed of himself, and laid down the pen. The next moment someone knocked at the door.

Already! He sat as still as a mouse and hoped that the person would just go away. But no, the knocking was repeated. He got up and moved towards the door.

As he was about to open the door Winston saw that he had left the diary open on the table. The letters DOWN WITH BIG BROTHER were big enough, and you could read the words across the room. It was a stupid thing. But, he realized, if he closed the book while the ink was wet, he would spoil the paper and he didn't want it.

He drew in his breath and opened the door. A small woman, with thin hair and wrinkles on her face, was standing outside. Winston was almost glad it was her.

«Oh, comrade», she began. Her sad high voice made you feel bored, «I thought I heard you come in. Do you think you could have a look at our kitchen sink? It's got blocked up and…»

It was Mrs. Parsons, the wife of a neighbor on the same floor. (You were supposed to call everyone «comrade» – but there were some women who you called «Mrs». without realizing it.) She was a woman of about thirty, but she looked much older. You could almost see dust on her face. Winston followed her to their flat. He had to do these small repair jobs almost daily. It annoyed him. Victory Mansions were old flats, built in the 1930s, and were falling to pieces. Unless you could manage yourself, you had to get permission for repairs. It could take up to two years to get it, even if it was just a window.

«Of course it's only because Tom isn't home», said Mrs. Parsons.

The Parsons' flat was bigger than Winston's, and also dark and dirty, but in a different way. It looked as if some large violent animal had just left it. All over the floor lay hockey-sticks, boxing-gloves, a burst football, a pair of shorts turned inside out. On the table there were dirty dishes and old exercise-books. On the walls were bright red banners of the Youth League and the Spies, and a full-sized poster of Big Brother. The flat smelt of boiled-cabbage just as the whole building, but there was also a smell of sweat. You could tell at once that it was the sweat of some person not present at the moment. In another room someone was trying to play the military music from the telescreen on a comb and a piece of toilet paper.

«It's the children», said Mrs. Parsons and looked at the door. «They haven't been outside today. And of course…»

She often didn't finishing her sentences. The kitchen sink was almost full with greenish water which smelt worse than ever of cabbage. Winston knelt down and examined the pipe. He hated using his hands. He also hated that he started coughing when he had to bend down. Mrs. Parsons stood next to him. She was helpless.

«Of course if Tom was home he'd repair in a moment», she said. «He loves anything like that. He's so good with his hands».

Parsons worked with Winston at the Ministry of Truth. He was rather fat but active and more than anything else he was stupid. The Party depended on him even more than on the Thought Police. He never questioned anything. At thirty- five he was forced to leave the Youth League. Before entering the Youth League he had managed to stay in the Spies for a year longer than anyone else. The work that he did at the Ministry didn't require much intelligence. He was a leading figure on the Sports Committee and all the other committees that organized different community activities. A strong smell of sweat followed him everywhere and even remained behind him after he had gone.

«Have you got a spanner?» said Winston.

«A spanner», said Mrs. Parsons. «I don't know, I'm sure. Perhaps the children…»

With a loud noise the children ran into the living-room. Mrs. Parsons brought the spanner. Winston let out the water and removed the human hair that had blocked up the pipe. He cleaned his fingers as best he could in the cold water and went back into the other room.

«Up with your hands!» shouted a voice.

A handsome boy of nine had appeared from behind the table. In his hands he was holding a toy pistol pointed at Winston. His small sister, about two years younger, did the same with a piece of wood. Both of them were wearing the blue shorts, grey shirts, and red neckerchiefs which were the uniform of the Spies. Winston raised his hands above his head. He had a strange feeling that it was not quite a game.

«You're a traitor!» yelled the boy. «You're a thoughtcriminal! You're a Eurasian spy! I'll shoot you, I'll vapourize you!»

They both started jumping round him, shouting «Traitor!» and «Thought-criminal!» It was a bit frightening. Winston saw that the boy wanted to hit or kick him and felt that he was very nearly big enough to do so. It was a good job it was not a real pistol, Winston thought.

Mrs. Parsons nervously looked from Winston to the children and back again. In the better light of the living-room he noticed that there actually was dust on her face.

«They get so noisy», she said. «They're disappointed because they couldn't go to see the hanging, that's what it is. I'm too busy to take them, and Tom won't be back from work in time».

«Why can't we go and see the hanging?» shouted the boy.

«Want to see the hanging! Want to see the hanging!» shouted the little girl.

In the Park, they were going to hang some Eurasian prisoners that evening, Winston remembered. This happened about once a month, and was very popular among children. He said goodbye to Mrs. Parsons and went to the door. But he had not gone six steps down the passage when something hit the back of his neck. He turned around and saw that Mrs. Parsons was pulling her son back into the flat while the boy put a catapult in his pocket.

«Goldstein!» shouted the boy as the door closed on him. Mrs. Parsons looked helpless and frightened.

Back in the flat he went quickly past the telescreen and sat down at the table again. His neck still hurt. The music from the telescreen had stopped. Instead, there now was a military voice.

That woman, he thought, must be really afraid. Another year, two years, and the children would be watching her night and day for unorthodoxy. Nearly all children were horrible these days. Because of such organizations as the Spies the parents couldn't bring them under control anymore, and yet the children never rebelled against the Party. They loved the Party and everything connected with it. The songs, the banners, the hiking, the toy pistols, the slogans, the Big Brother – it was all a sort of game to them. All their violence was turned against the enemies of the State, against foreigners, traitors, thought-criminals. It was almost normal for people over thirty to be afraid of their own children. Nearly every week you could read in the Times how some «child hero» had reported its parents to the Thought Police.

Читать дальше