Anyway, it’s sort of hypocritical that Davey would all of a sudden change his mind. This is all probably just part of some kind of postwar flip-out.

“I’m telling you,” Davey says. “It isn’t safe.”

I nod, pretending this makes sense. When Ralph heard Davey was home, he told me about PTSD and how it’s mainly about soldiers not being able to let go of the drama of war. Like, they’ve been trained to sit around listening for explosions or footsteps, but now that’s no longer necessary and they’re not supposed to kill anybody, either. Their survival instinct’s on full blast and all the controls are stuck.

Davey raises his eyebrows at me. “I mean I know everybody wants this to be over, but it’s not exactly over if they’ve got the wrong guy, is it?”

“Hm.” I should probably change the subject. “So, when do you go back to battle?” I shouldn’t have said that.

Davey gestures with his bandaged hand. “You don’t go back once a body part is missing, Kippy. They don’t let you.”

I let out this weird squawking laugh, then lower my voice, trying to sound conspiratorial. “How’d that happen anyway?” I tap the bandage where his finger should be and he recoils in pain. “Sorry!” I reach for his beer can. “Here—oh, it’s empty—but maybe it’s sort of like an ice pack still.” I press the can to his nonfinger and he howls.

“Just.” He hisses through his teeth. “I appreciate it, just sit there, okay.” He cracks another beer and offers it to me. I shake my head—Dom would have a meltdown. Plus, there’s always the chance he might swing by unexpectedly to make sure I’m chaperoned. He’s been showing up at the Frieds’ out of nowhere like that ever since I turned thirteen. “Where are your parents, anyway?” I ask, trying not to sound nervous.

Davey grimaces. “They bailed this morning. Staake came by early to tell them. Dad was basically comatose and Mom kept stressing about running into the Widdacombes at the grocery store.”

“So, no parental supervision?” I bite my lip. Dom would lose it if he knew.

Davey gives me a look.

“I’m just kidding,” I stammer. “It’s not like I’m some baby who needs grown-ups or something. It was a joke.” I force a laugh. “They are gone though, right? Like officially?”

He shrugs. “They’re off on some Canadian retreat thing to save their marriage. They signed up as soon as the cops found Ruth, but decided to go early once they found out about Colt. Real problem solvers, those two.” Davey motions for me to take the beer again but I shake my head more firmly this time. “The truth is I think they hated being around me.” He starts drinking the beer he offered me. “I think when one of your kids dies, you hate the other one for a while. I kind of get that.” I notice he’s sort of started to slur his words.

“Listen, stop it.” I pluck the beer from Davey’s hand and put it by my feet. “This is an official intervention. I’ve read lots of books about grieving, and pretty much all of them say drunken despair is not the way to cope because it keeps you stuck. No more Beast.”

Davey looks at me like I’m crazy. “You know, I can just open another one.”

“No, because I want to know about Colt. And I need you to make sense. How come he didn’t do it?” If Davey’s going to have his own version of a postgrief obsession, then I’m going to sit here and encourage him to get on with it—sober. “I’m listening, okay?” Ruth might have been a bad friend, but that doesn’t mean I have to be. “Now start from the beginning. Tell me everything.”

Sometimes at school Ruth would see Colt in the hallway and leap straight into his arms. “Yo girl, stop broadcasting our business,” he’d say. But usually he’d catch her. She used to say she “loked” him. That she was on the verge—“the precipice,” she said—between like and love.

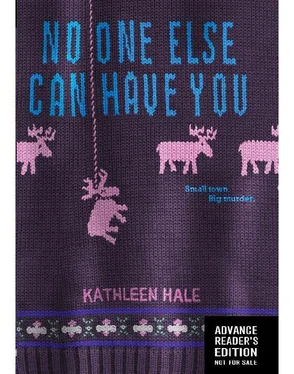

“It’s scary how much I loke him,” she told me. “Because I’m like, ‘Ugggh, Colt, maybe I’ll kill you so no one else can have you.’ It’s like I can’t get close enough or something.”

I always knew exactly what she meant—how sometimes there’s this slamming need for proximity, and you want to show someone the full weight of your attention by laying it on them, head to toe. After Mom died, I’d lie in wait, then pounce on Dom, yelling “ banzai! ” while I got a foothold on his neck or shoulder blade. I’d wrestle Ruth’s dogs until they yelped, or squeeze Mother Peanut Butter so hard she could barely hiss. This thought would pulse through my brain: “I have so much love to give and nowhere to put it!” and then Dom would have to pry Mother Peanut Butter from my fingers.

“All right, Miss Huggersmith, calm down,” he’d say.

Eventually I had to go to a support group about it. But even after I learned to control myself better, I still felt that way, especially around Ruth. I loved to hug her, which she always seemed fine with—at least to a certain point. I just always felt so grateful to her for wanting to be around me. When we were kids, I would sometimes cling to her like a koala. “Personal space, Kipster,” she’d remind me. And I’d reluctantly retract my claws.

So I get it in a way—I mean, I still think that love is mostly about wanting someone to be alive forever, even though that’s impossible—and I’m not saying that Ruth brought it on herself for being huggable, or anything, just that the whole Colt thing makes sense to me now on more than one level. I mean there’s real evidence, for starters—all that DNA. But also if you really like someone, and want to really lay it on them, well, you could turn into a monster, probably. Especially if you had something really dark already lurking deep inside of you.

Colt is guilty. Davey will understand that, eventually. He just needs somebody to talk him through it—to take up the opposing argument—and I can do that. I mean, I might be really good at saying the wrong thing, but I also took debate class last semester.

Davey huffs. “Okay, for starters, Colt hooked up with Staake’s daughter. If I were Staake, I’d still be pretty pissed about that. I’d have a fucking vendetta.”

“So what,” I explain. “Everyone’s hooked up with Lisa Staake.” It’s true. She’s like some kind of blonde rabbit in heat.

“And in terms of the evidence—of course Ruth’s hair was all over Colt’s car,” Davey continues. “They were dating, for God’s sake. They probably saw each other that day at school. Of course she had his DNA on her hands or whatever.”

I raise my eyebrows meaningfully. “Yeah, but Sheriff Staake says it was other places, too.” I don’t want to bring up sex, specifically, but Davey saves me the trouble.

“Maybe they did it at school that day, or something.” He shrugs. “That was sort of Colt’s style.”

“Ew.” I wrinkle my nose.

“Oh come on, Kippy, think about it: Staake needed a fall guy because the whole town was about to have a stroke.” He rolls his eyes. “You know how Friendship is. No one wanted to think about it anymore—when was the last time people around here decided to dwell on anything?—and Staake wanted to make himself popular by easing the tension. And the thing is, Staake’s not that bright. My parents went to high school with him and were telling me he barely graduated. The guy was a numbskull. They were both livid that he was even handling the case. And you know what? When I was in high school, Staake planted weed on some of the potheads in my grade—not something I can prove, obviously, but I knew those guys okay, and they weren’t the kind of dumb where they’d keep marijuana in their lockers.” He reaches down by my feet and retrieves the beer I confiscated. “I told my dad about it and he said there’d always been rumors that Staake liked to cut corners.”

Читать дальше