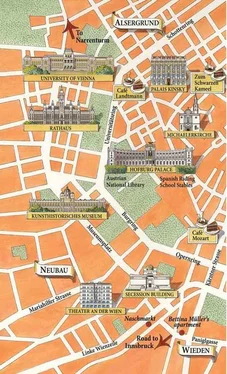

Sarah thought of how she’d been catching glimpses of Beethoven all over Vienna. Did she really have the power to see him? Did she only need to give herself permission?

“Lovely,” said Elizabeth. “No sense wasting good drugs. Ingredients are so hard to come by these days. I had to order powdered lion heart from some redneck animal dealer in Texas, for God’s sake. Now. Sarah. Pols is waiting. Time, my dear. Time. We need to make a deal.”

“Fine!” Sarah snapped. “What do we need to do to speed this show along?”

Elizabeth kneeled and bent her head in prayer for a moment.

“So you’re not kidding?” Nico said. “You could bring back Aristotle, or Jesus, or Seabiscuit. And you’re bringing back—”

Elizabeth was eye to eye with him. “Tell me, Jepp, wasn’t there a girl . . . why, I believe she was Tycho’s sister. Sondra, was it?”

“Sophie,” said Nico quietly.

“Wouldn’t you like to see her again?”

Nico seemed to struggle with himself for a moment, then said harshly, “Not on this side of things.”

Sarah saw Hermes stick his nose out of Nico’s suit pocket. The little man pushed him back down.

“Max, spread out the folio,” he barked. “Sarah, put that vial away for now.”

“Harriet, you’re going to love this!” cried Elizabeth. “The portal was hidden by alchemy, and only alchemy will reveal it. It’s magic time.”

“I assume you have the ingredients?” asked Nico.

“Removed for curatorial purposes from across the land,” sang Elizabeth, pointing to the pile of boxes. “The hardest to find was a sixteenth-century Venezuelan fruit fly preserved in amber. A favorite ingredient of Philippine’s. That was hidden, if you please, in a galleon inside the British Museum.”

“That’s what was in the galleon?” Sarah swung around. “I got high off a fruit fly ?”

“What on earth are you talking about?”

“The cannon in the secret compartment in the galleon. I got blasted with it.”

Elizabeth smiled.

“Oh, that. That was just a wee something Philippine stored for Rudolf. A nice little seventeenth-century tonic for the vagus nerve. Not important. If you had popped off the head of the emperor figure on the ship, you would’ve found the fruit fly. Not that you would’ve known what to do with it. Anyway, thanks ever so for returning the galleon. I decamped from Vienna so quickly, I didn’t have time to dispose of it. And I always cover my tracks. So. Let’s begin. Nico, read out the instructions.”

Sarah watched as Elizabeth sprinkled various powders and liquids and objects at precise points in the room. A lifetime’s worth—no, several lifetimes’ worth—of collected ingredients. The feather of a dodo. A meteorite from the asteroid Vesta. Tears of an elephant shed during sorrow. A sparrow’s egg impregnated with twins.

Elizabeth gathered powdered vials of gold, silver, and copper, and set a large hourglass in the center of the room Nico took a piece of chalk, marched off the paces, and drew celestial symbols on the terra-cotta floor tiles—the Sun, the Moon, and Venus. Elizabeth emptied the vials onto the chalk symbols.

“Iron, tin, lead, and quicksilver,” said Nico. “Here, here, here, and here.” He drew the symbols for Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and Mercury. He seemed to be almost in a trance. “It’s been a long time,” he said. “I helped the Master draw this circle many times.”

“As I assisted my stepfather,” said Elizabeth. “Cardinal, mutable, fixed, calcination, congelation, fixation . . .”

“Distillation, digestion, solution,” added Nico. “Sublimation, separation, creation . . .”

“Fermentation, multiplication, projection.”

“Abracadabra,” said Sarah. “I’m waiting here.”

“Now, we do need someone to take my daughter’s place in the past. I had to send Kubiš and Nepomuk back through because if someone comes out, someone must go in. Or things are out of balance.” Elizabeth pointed at Harriet. “You,” she said, “are going to have such a lovely trip.”

“Harriet”—Max moved to her side—“you don’t have to do this.”

“I think it’s all so fascinating,” said Harriet, swaying. “Don’t you?” She stumbled toward Elizabeth. “I’m ready.”

“The time is right,” said Nico. “We must marry the red and the white, Mercury and Sulfur.”

Nico and Elizabeth began chanting something in Latin. “Ut supra sub ratione temporis unum spatium itineris conficiendi hic spiritus flectatur dimittam . . .”

And then the floor began to rumble.

Many of the alchemists were seriously good engineers, Sarah reminded herself, as the floor began moving under her feet. The stones were rearranging themselves by some unseen force, like domino tiles. The whole building began to shake. Plaster bits fell from the ceiling, and each of them—Sarah, Elizabeth, Harriet, Max, Nico—retreated from the center of the room as the stones slid away to reveal a short flight of stairs down into darkness. Sarah lurched forward. The key around her neck was vibrating, tugging her down to her knees.

“The portal is down there,” Elizabeth said. “But before you open it you must find my daughter.”

“Not until Pols is safe,” Sarah warned.

“I get my girl, you get yours,” said Elizabeth. She dragged a large cardboard box from the corner and began slicing away the sides.

“Why don’t you take the drug and see her yourself?” asked Sarah, stalling. “It’s named after you.”

“Hasn’t the dwarf told you? It doesn’t work on us. Our cells are modified in a way that makes it ineffective.” She pulled the last of the box away and dragged out a . . .

An armonica. A glass armonica.

“Where did you get that?” Sarah moved forward. “It’s not . . . Mesmer’s armonica, is it?”

“Quiet. Now, help me bring this down the steps. Portia will still be weak and ill when she comes through the portal. I will need to keep her alive until I determine what drugs will cure her for good. I will not give her immortality in a sick body. Come, all of you. You, too, Harriet. You must be ready to enter the portal.”

They descended the steps with their awkward burden. The staircase led to a small, round room.

It was the round room from her dreams. But there was only one door here, a rather innocuous-looking trapdoor in the floor. The key around her neck was jumping now. Elizabeth moved the armonica to a position a few feet from the portal.

She looked at Sarah. “Now. Find her.”

“It’s not that simple,” Sarah snapped. “I can’t just turn it on and off. And I get confused easily.”

“We were here,” said Elizabeth. “Upstairs.” She pointed to the opening at the top of the steps. “My daughter and I were here. It was the last day in April. They opened up the palace on Walpurgis night, and we came. Portia was wearing a red cape. We stood upstairs, with the rest of the revelers, drinking hot wine.”

There was a new tone to Elizabeth’s voice. Plaintive.

“Look for her. She’s here. It was Carodejnice . Walpurgis. The emperor opened the gates of the preserve to the townspeople for the bonfire, spreading a little goodwill to counter the purges. I know you can find her.”

Sarah moved back to the steps.

“Don’t use your eyes. Feel her. Like music. Feel her,” Elizabeth whispered.

Sarah closed her eyes. Hundreds and hundreds of people over the centuries had wandered through the room above them. She must not get distracted. Her mind stretched out, seeking. She could smell chestnuts in the air, hear something howling in the woods outside the palace. Walpurgis in the early seventeenth century. The pagan rite that marked the end of winter. Sarah wasn’t sure when the local populace had transitioned from annually burning a real live woman to burning a straw witch. Maybe not yet, she realized.

Читать дальше