A single death glare from Kramer, though, and she clammed up. Fine. Be ignorant. Mangle science. See what she cared.

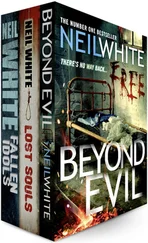

After that, the class drifted to horror, specifically Wisconsin’s Most Famous Crazy Dead Writer, Frank McDermott, who was originally from somewhere in Wyoming and lived in England a good long time, but who was keeping score? Besides writing a bazillion mega-bestsellers, McDermott’s claim to fame was getting blown to smithereens by his equally wacko nutjob of a wife. (Ed Gein, Jeffrey Dahmer, Frank Lloyd Wright and the Taliesin murders, McDermott—Wisconsin was full of ’em. Had to be something in the water.) With his new! important! biography! Kramer hoped to solve the BIG MYSTERY: where was Waldo … er, Frank? Because, after the explosion, not one scrap of McDermott remained, not even his teeth. Which was a little strange.

Originally a quantum physics star—lotsa theories about multiverses and timelines and blah, blah—Meredith McDermott was fruitier than a nutcake. Years in institutions, suicide attempts—the whole nine yards. Maybe she turned to glass art the way a patient might take up painting, but what she made was unreal; museums and collectors fell all over themselves snapping up pieces.

Turned out the lady was also a complete pyro. She would’ve had plenty on hand in her studio, too: propane tanks, cylinders of oxygen, acetylene, MAPP. To that she’d thrown in gasoline and kerosene and, as a kind of exclamation point, a bag of fertilizer.

The fireball was immense. The explosion chunked a blast crater seventy feet long and fifteen feet deep. Emma bet Old Frank was tip-typing away in writer heaven before he knew he was dead.

Even so, there ought to have been plenty of Frank McDermott shrapnel: bits and pieces zipping hither and thither at high speeds to get hung up on branches or blast divots into tree trunks. Science was science. No matter what the movies said, for a person to completely vaporize, you needed either an atomic bomb or about a ton of dynamite. So why couldn’t the police find a single, solitary bone? A watch? Something? All that was recovered at the scene were the barn’s iron bolts, sliders, and hinges—and a coagulated lake of slumped, amorphous glass.

And only the barn burned. The house hadn’t. Neither had Meredith’s workshop or the woods or even the fields, despite the fact that the local fire department was twenty miles away and no response team arrived until hours after the explosion. Just plain weird.

And where was Meredith? What happened to the McDermotts’ little kid? All the police ever found was the family car, miles away after it lost an argument with a very big oak. No bodies, though. Just a dead car.

And a whole lotta blood.

6

THE UNFINISHED MANUSCRIPTSwere also weird.

Three—and there might be more—were quietly decomposing under house arrest in some vault in England. No one was allowed to see or handle them, period. All scholars like Kramer got were a few choice bits copied from the originals: not enough to make much sense of the stories but just enough to whet their appetites.

This tallied, though. McDermott was a squirrel. Not even his editors were allowed to hang on to his original manuscripts, which were penned on homemade parchment scrolls—no one was quite sure whether these were vellum or the hide of some more exotic animal—with a special ink McDermott also formulated himself. Since the guy made more money than God, the editors put up with it. They also mentioned how the longer they handled those scrolls, the more the ink changed color to a shade as vibrant as freshly clotted blood , as one editor put it. Even this wasn’t necessarily news. From the description, Emma thought McDermott’s brew must be chemically related to iron gall ink, which oxidized with exposure to air. In other words, the ink rusted, and the stuff literally ate through parchment. All the academics made this sound so spooky , but honestly, it was just chemistry. Mozart and Rembrandt and Bach used the same ink. So did Dickens. BFD. All McDermott had done was tweak the original recipe so his work had a built-in termination date: a nice way of sticking it to people like Kramer. Give McDermott an A for effort; Emma almost admired the guy.

Probably would have, if she hadn’t been so freaked about her story.

7

WHAT KRAMER HANDEDher was a fragment—a note, really—from a book she’d never read, because McDermott never got around to writing it. All that scholars like Kramer knew about this novel, Satan’s Skin , came from this and a few other jotted entries. The plot involved a demon-grimoire stitching itself back together, only the pages had been reused in other books and so the characters kept jumping off the page while debating the nature of quantum realities. Some loopy Matrix meets Inkheart -with-a-vengeance crap like that.

Her story was about these eight kids stranded in a spooky house during a snowstorm who begin to disappear one by one. Okay, it wasn’t all original; she’d taken a cue from this awesome John Cusack movie. (Sure, the film was completely freaky. All the characters turn out to be alters: different personalities hallucinated by this completely insane, wacko killer. But the idea that people who thought they were real weren’t— well, it was just so cool.) Her first draft had written itself, pretty much. Considering how writing creeped her out, this should’ve tripped some alarms.

As it happened, her story was a subplot of Satan’s Skin . There were differences. In McDermott’s version, the kids—and yeah, there were eight—were nameless. The oldest, a complete psychopath, murdered his nasty drunk of a dad, who deserved it, the abusive SOB. (All McDermott’s dads and quite a few moms were the same, too. Guy had some serious parental unit issues.) In her version, the characters had names, but her hero—this sweet, sensitive, gorgeous, hunky, completely yes-please guy—had killed his nasty dad in self-defense and was haunted by what he’d done.

Both her draft and McDermott’s fragment shared something else: neither ended. Kramer said McDermott’s note stopped in midsentence, a little like Edwin Drood , although Dickens had the decency to put in a period before up and dying. Hers was like McDermott’s. Not only had she written herself into a corner; she couldn’t figure a way to tie up all those loose ends. The last sentence just sort of floated all by its lonesome. Since her assignment was only a first draft, she had the go-to of needing feedback from the Great Bloviator … er, Kramer.

But, to be honest? Imagining a final period or the end set up a sick fluttering in her stomach. She just couldn’t do it. She’d never admit this to a soul, but … well … her hero was the perfect guy and she … she really liked him. In that way. Okay, okay, fine, she even daydreamed about him, and how lame was that? Mariane had this stalker thing for Taylor Lautner—seriously, the girl was obsessed with those pecs and that six-pack—but at least she drooled over a real guy. Emma’s perfect boyfriend was an idea that lived in her head, but he was also so real , the most well-rounded of her characters. The others were just one-dimensional placeholders. This guy she actually thought of as a complete person. Wrapping up his story would be so final , a lowering of that damn bell jar. Once done, her guy was finished, no way out of the box—not unless she decided to chuck science and write herself into The Continuing Adventures of Emma Lindsay, Loser and Social Misfit . Maybe that was why writers did sequels; they just couldn’t let the story really die.

Читать дальше