“Ah, so.”

“Well, I have this one jay that somebody laid on me a while ago. I didn’t know how you would react so I never said anything about it. I could get it.”

“How does it mix with liquor?”

“I don’t know. I never used to drink. One joint between the two of us can’t do too much anyway. Should I get it?”

He grinned. “Mrs. Kleinschmidt wouldn’t approve,” he said.

“I’ll be back in a minute.”

He had not been able to remember the feeling. But now he was able to recognize it, just as he had recognized the smell the instant she lit the misshapen little cigarette. And he remembered the elaborate ritual of dumping half the tobacco from a regular cigarette and dropping the roach in so that not a crumb of the marijuana would be wasted. They had called it tea then, and the cigarettes were called reefers, or sticks if you were especially hep. He couldn’t remember any special name for the butts. A roach, in those years, was something that crawled around the bathroom.

He sat back on the couch and closed his eyes. Yes, he remembered the feeling. How could he have forgotten the feeling? For that matter, how could he have gone smugly without it all these years? It did feel nice. There was no getting away from it — it felt very nice indeed.

“Daddy?” Her voice was so soft and lazy. “How are you feeling?”

“Far-out,” he said, and laughed.

“Let me look at your face. That’s such good dope. Oh, you’re so stoned!”

“Far-out.” “Oh, wow.”

“Where are you going?”

“Get more drinks. Throat’s dry.”

“You didn’t take the glasses.”

“How can I get the drinks without glasses?”

“That’s what I said.”

“So did I.”

“So did you what?”

“Huh?”

They both started to giggle. It was funny, he thought. You would get into a sentence and your mind was doing such interesting things and doing them so quickly that you forgot what the sentence was about before you could get to the end of it. He pursued this thought, considering all its implications, following them through to wherever they led him and then trying to remember what he had just thought of. One connection in particular struck him as meaningful, and he decided to tell Karen about it when she got back. Then he realized she was sitting beside him.

“I thought you were going to get the drinks.”

“Oh, man, are you wrecked!”

“Huh?”

“What have you got in your hand?”

He looked. He had a glass of scotch in his hand and no idea on earth how it got there.

He said, “I’m not stoned at all.”

“Right.”

“It’s a magic trick. A power I have. Whenever I want a drink I just wish for it and a glass turns up in my hand.”

“You silly Daddy.”

Later she said, “I’ve been wanting to ask all day. I read the, uh, the dedication page.”

“And you don’t want it dedicated to you.”

“Don’t even say it. I guess I was wondering what made you decide to dedicate it to me.”

He put his hand on her knee, squeezed. The disorientation of the marijuana high had abated now. He was still stoned, but in a way that did not interfere with linear thought. He just felt very good, very happy, utterly relaxed.

He said, “Do you remember when I was stuck on the book and then in the middle of a conversation with you I went in there and started writing like a maniac?”

“Of course I remember. I brought you coffee and you didn’t even know I was there.”

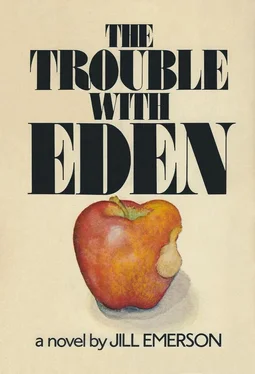

“Well, that same day I typed out the dedication page. You gave me the help I needed. I don’t even remember what it was you said, what we were talking about, but before then the book was all from the wife’s viewpoint.”

“And you got the idea from me of bringing in the daughter?”

“She would have been a character anyway. But now it’s a whole different book.” He explained to her some of the ways the book had developed. “I shouldn’t be telling you all this,” he added.

“You mean like trade secrets?”

“Hardly. No, I mean a reader should be able to think that a book happened in one particular way because it couldn’t have happened in any other way.”

“It couldn’t have.”

He had just been thinking that himself. In this book, more than any other he had written, the characters had insisted upon speaking their own lines.

“So that’s why you dedicated it to me. I was wondering.”

“Why did you think?”

“I don’t know.”

“It would have wound up dedicated to you anyway. The way it turned out.”

“It’s about me, isn’t it?”

“Did you feel that?”

“Only on every fucking page. It was almost scary.”

“She’s not precisely you.”

“An awful lot of her is. To me, anyway.”

“Yes, a great deal of her. The relationship.”

“Right.”

“Having you here has taught me a lot about fathers and daughters, Karen. Any honest book has to grow out of what a man knows.”

“I was so proud of her.”

“Were you? So was I.”

“I was so proud that you, that you felt, that the way you think of me — I don’t know how to say it.”

He put his arm around her. Her head settled on his shoulder.

At one point he stacked some, records on the record player. At another point he went into the-kitchen and came back with bottles of scotch and soda and a bowl of ice cubes. “It’s the running around that gets to you,” he said then. “A person can stand a long night of drinking, but all that walking back and forth is bad for the legs.”

And it was shaping up as a long night of drinking. They were talking less now that the music was playing, frequently lapsing into long silences with her head on his shoulder and his arm around her. He would think now and then that it was late, that they had already done more than enough drinking, that they ought to go to sleep. But it was too perfect a night to end, and neither of them ever suggested ending it.

Eventually they were talking again about the book. He said that he would have to proofread it soon, and how he hated proofreading. She offered to do it for him.

“I’ll have to do it myself,” he said. “So I can see what has to be revised.”

“Nothing has to be revised.”

“Well, I’ll have to go through it anyway and make sure.”

“But I’ll proofread the galleys,” she said.

“Oh, that won’t be for almost a year. That’s a long ways off.” She stiffened. “Kitten? What’s the matter?”

“Nothing.”

“Did I say something?”

“No,” she said. But her face was troubled. “I just—”

“Tell me.”

“You mean I won’t be here then.”

“I didn’t mean that.”

“But I won’t, will I?”

“Where are you off to?”

“Do you mean I can stay?”

“Of course you can stay. This is—”

“I’m not in the way?” There were tears in her eyes. “I just don’t want to go anywhere,” she said. “I just feel so good here. I feel guilty about it.”

“Guilty?”

“I just love being with you,” she said. “I don’t ever want to go away.”

“Oh, kitten.”

“Look at me, I’m shaking. I’m all funny inside. Oh, please hold me.” He said, “Easy, baby. Easy now.” He held her close and stroked her hair while she wept against his shirt. “Easy,” he said, touching her hair, rubbing the back of her neck. “Oh, stay forever,” he said. “Don’t ever go. Don’t ever leave me.”

“Oh—”

He tipped up her chin and kissed her. He kissed her, and she was his daughter, his flesh, and he loved her. He kissed her and she was every woman he had ever wanted, all he had ever wanted, and her arms were around his neck and her lips were parted and he was kissing her now with his heart pounding and his tongue in her mouth and his hands on her back, feeling her, caressing her, and her flesh trembled in response, and—

Читать дальше