As mentioned earlier, in GNU Emacs only the buffer name is displayed on the mode line, rather than the buffer name and the filename. Even if you rename a buffer that contains a file, Emacs remembers the connection between buffer and file, which you can see if you save the file ( C-x C-s) or display the buffer list (described later in the chapter).

What if you have two buffers with the same name? Let's say you are editing a file called outline from your home directory and another file called outline from one of your subdirectories. Both buffers are called outline, but Emacs differentiates them by appending <2>to the name of the second buffer. (You can tell which is which by looking at the buffer list, discussed later in this chapter.) Emacs offers an option that adds a directory to buffers in this situation: select Use Directory in Buffer Names from the Options menu. Let's say you've turned on this option and are editing a file called .localized ; Emacs will call this buffer simply .localized. Now you find a second file of the same name from a subdirectory. Instead of calling this buffer .localized<2>, Emacs names the buffer directory /.localized, making it easy for you to tell the buffers apart at a glance. This option has some limitations. It shows only the parent directory, not the full path, and it shows directory names only if multiple buffers have the same name. We wish it would go a bit further and provide the option of including the directory on the mode line for all buffers.

One word of advice: if you have a lot of buffers with names like proposal, proposal<2>, and proposal<3>around, you're probably forgetting to edit the directory when you ask for a file. If you try to find a file but get the directory wrong, Emacs assumes you want to start a new file. For example, let's say you want to edit the file ~/work/proposal , but instead ask for the file ~/novel/proposal . Since ~/novel/proposal doesn't exist, Emacs creates a new, empty buffer named proposal. If you correct your mistake ( C-x C-f ~/work/proposal), Emacs renames your buffers accordingly: your empty buffer proposalis associated with ~/novel/proposal ; the buffer you want is named proposal<2>.

Here's a hint for dealing with the very common mistake of finding the wrong file. If you notice that you've found the wrong file with C-x C-f, use C-x C-vto replace it with the one you want. C-x C-vfinds a file, but instead of making a new buffer, it replaces the file in the current buffer. It means "get me the file I really meant to find instead of this one." Using this command circumvents the problem of having unnecessary numbered buffers (i.e., proposal, proposal<2>, and so on) lying around.

While you're working, you may need to read some file that you don't want to change: you just want to browse through it and look at its contents. Of course, it is easy to touch the keyboard accidentally and make spurious modifications. We've discussed several ways to restore the original file, but it would be better to prevent this from happening at all. How?

You can make any buffer read-only by pressing C-x C-q. Try this on a practice buffer and you'll notice that two percent signs ( %%) appear on the left side of the mode line, in the same place where asterisks ( **) appear if you've changed a buffer. The percent signs indicate that the buffer is read-only. [22]If you try to type in a read-only buffer, Emacs just beeps at you and displays an error message ( Buffer is read-only) in the minibuffer. What happens when you change your mind and want to start editing the read-only buffer again? Just type C-x C-qagain. This command toggles the buffer's read-only status—that is, typing C-x C-qrepeatedly makes the buffer alternate between read-only and read-write.

Of course, toggling read-only status doesn't change the permissions on a file. If you are editing a buffer containing someone else's file, C-x C-qdoes not change the read-only status. One way to edit someone else's file is to make a copy of your own using the write-filecommand, and then make changes. Let's say you want to change a proposal that is owned by someone else. Read the file, write the file as one you own using C-x C-w, then change it from read-only to writable status by pressing C-x C-q. None of this, of course, modifies the original file; it just gives you a copy to work with. If you want to move a minor amount of text from a read-only file to another, you can mark the text then press M-wto copy it. Move to the place you want to put the text and press C-yto paste it.

You can open a file as read-only in a new window by typing C-x 4 ror in a new frame by typing C-x 5 r. This is one of a number of commands in which 4 means window and 5 means frame.

4.5.4 Getting a List of Buffers

Because you can create an unlimited number of buffers in an Emacs session, you can have so many buffers going that you can't remember them all. At any point, you can get a list of your buffers (yes, we know you know how to do that by holding down Ctrland clicking the left mouse button, but this is a little different). This list provides you with important information—for example, whether you've changed the buffer since you last saved it.

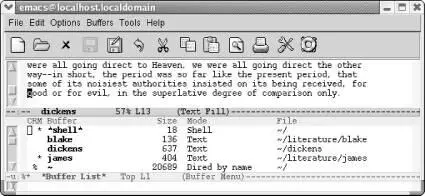

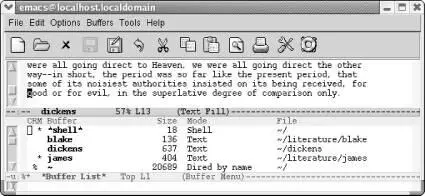

If you press C-x C-b, Emacs lists your buffers. It creates a new *Buffer List*window on the screen, which shows you all the buffers.

Type: C-x C-b

Emacs displays a list of buffers.

You can use this list as an informational display ("these are my buffers") or you can actually work with buffers from this list, as covered in the next section.

Figure 4-3shows what each of the symbols in the buffer list means.

Figure 4-3. Understanding the buffer list

4.5.5 Working with the Buffer List

The buffer list is more than a display. From the buffer list, you can display, delete, and save buffers. To move to the buffer list window, type C-x o. Emacs puts the cursor in the first column. For a particular buffer, press nor C-nto move down a line or por C-pto move up a line. You can also press Spaceto move down to the next line and Delto move up. (The up and down arrow keys work, too.) This array of up and down choices may seem confusing, but multiple bindings are given to make it easy to move up and down without consulting a book like this one.

You use a set of one-character commands to work with the buffers that are listed. To delete a buffer, go to the line for the buffer you want to delete and type dor k. The letter Dappears in the first column. You can mark as many buffers for deletion as you want to. The buffers aren't deleted immediately; when you're finished marking buffers, press x(which stands for "execute") to delete them. If any of the buffers you want to delete are connected with files, Emacs asks if you want to save the changes before doing anything. (Note that it does not ask you about buffers that aren't connected with files, so be sure to save any that you want before deleting them.)

Читать дальше