You can do the following with C-x b:

| If you type C-x b followed by: |

Emacs: |

| A new buffer name |

Creates a new buffer that isn't connected with a file and moves there. |

| The name of an existing buffer |

Moves you to the buffer (it doesn't matter whether the buffer is connected with a file or not). |

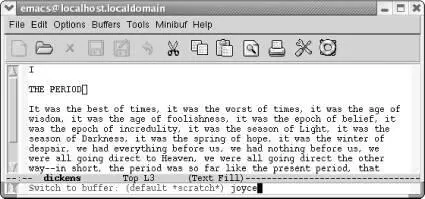

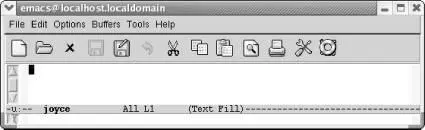

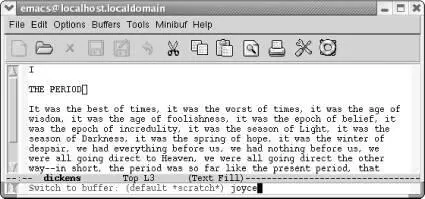

If you want to create a second (or third or fourth, etc.) empty buffer, type C-x b. Emacs asks for a buffer name. You can use any name, for example, practice, and press Enter. Emacs creates the buffer and moves you there. For example, assume you've been working on your tried-and-true dickensbuffer. But you'd like something new, so you start a new buffer to play with some prose from James Joyce.

Type: C-x b joyce

You typed a new buffer name.

Type: Enter

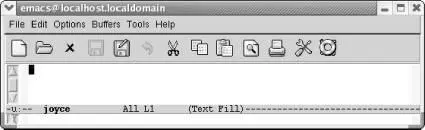

Now you have a new buffer named joyceto type in.

This procedure isn't all that different from using C-x C-f; about the only difference is that the new buffer, joyce, isn't yet associated with a file. Therefore, if you quit Emacs, the editor won't ask you whether or not you want to save it.

C-x bis especially useful if you don't know the name of the file you are working with. Assume you're working with some obscure file with an unusual name such as .saves-5175-pcp832913pcs.nrockv01.ky.roadrunner.com . Now assume that you accidentally do something that makes this buffer disappear from your screen. How do you get .saves-5175-pcp832913pcs.nrockv01.ky.roadrunner.com back onto the screen? Do you need to remember the entire name or even a part of it? No. Before doing anything else, just type C-x b. The default buffer is the buffer that most recently disappeared; type Enterand you'll see it again.

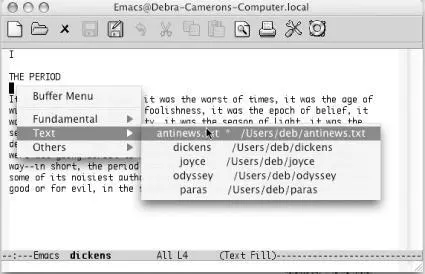

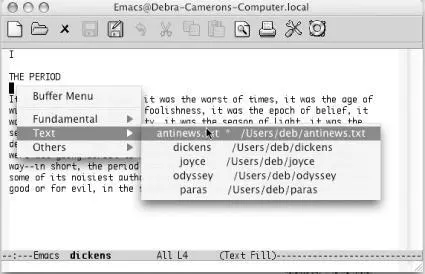

Alternatively, the Buffer Menu popup lists buffers by major mode, and you can choose one. Hold down Ctrland click the left mouse button to see a pop-up menu of your current buffers. (The Buffers menu at the top of the screen also shows all current buffers.)

Hold down Ctrland click the left mouse button.

Emacs displays a pop-up menu of current buffers by mode (Mac OS X).

To cycle through all the buffers you have, type C-x→ to go to the next buffer (in the buffer list) or C-xto go to the previous buffer. (Don't hold down Ctrl while you press the arrow key or Emacs beeps unhappily.)

It's easy to create buffers, and just as easy to delete them when you want to. You may want to delete buffers if you feel your Emacs session is getting cluttered with too many buffers. Perhaps you started out working on a set of five buffers and now want to do something with another five. Getting rid of the first set of buffers makes it a bit easier to keep things straight. Deleting a buffer can also be a useful emergency escape. For example, some replacement operation may have had disastrous results. You can kill the buffer and choose not to save the changes, then read the file again.

Deleting a buffer doesn't delete the underlying file nor is it the same as not displaying a buffer. Buffers that are not displayed are still active whereas deleted buffers are no longer part of your Emacs session. Using the analogy of a stack of pages, deleting a buffer is like taking a page out of the current stack of buffers you are editing and filing it away.

Deleting buffers doesn't put you at risk of losing changes, either. If you've changed the buffer (and the buffer is associated with a file), Emacs asks if you want to save your changes before the buffer is deleted. You will lose changes to any buffers that aren't connected to files, but you probably don't care about these buffers.

Deleting a buffer is such a basic operation that it is on the Emacs toolbar, the X symbol. Now let's learn how to do it from the keyboard to increase your fluency in Emacs.

To delete a buffer, type C-x k(for kill-buffer). Emacs shows the name of the buffer currently displayed; press Enterto delete it or type another buffer name if the one being displayed is not the one you want to delete, then press Enter. If you've made changes that you haven't yet saved, Emacs displays the following message:

Buffer buffer name modified. Kill anyway? (yes or no).

To ditch your changes, type yes, and Emacs kills the buffer. To stop the buffer deletion process, type no. You can then type C-x C-sto save the buffer, followed by C-x kto kill it.

You can also have Emacs ask you about deleting each buffer, and you can decide whether to kill each one individually. Type M-x kill-some-buffersto weed out unneeded buffers this way. Emacs displays the name of each buffer and whether or not it was modified, then asks whether you want to kill it. Emacs offers to kill each and every buffer, including the buffers it creates automatically, like *scratch*and *Messages*. If you kill all the buffers in your session, Emacs creates a new *scratch*buffer; after all, something has to display on the screen!

Windows are areas on the screen in which Emacs displays the buffers that you are editing. You can have multiple windows on the screen at one time, each displaying a different buffer or different parts of the same buffer. Granted, the more windows you have, the smaller each one is; unlike GUI windows, Emacs windows can't overlap, so as you add more windows, the older ones shrink. The screen is like a pie; you can cut it into many pieces, but the more pieces you cut, the smaller they have to be. You can place windows side-by-side, one on top of the other, or mix them. Each window has its own mode line that identifies the buffer name, the modes you're running, and your position in the buffer. To make it clear where one window begins and another ends, mode lines are usually shaded.

As we've said, windows are not buffers. In fact, you can have more than one window on the same buffer. Doing so is often helpful if you want to look at different parts of a large file simultaneously. You can even have the same part of the buffer displayed in two windows, and any change you make in one window is reflected in the other.

The difference between buffers and windows becomes important when you think about marking, cutting, and pasting text. Marks are associated with buffers, not with windows, and each buffer can have only one mark. If you go to another window on the same buffer and set the mark, Emacs moves the mark to the new location, forgetting the place you set it last.

As for cursors, you have only one cursor, and the cursor's location determines the active window. However, although there is only one cursor at a time, each window does keep track of your current editing location separately—that is, you can move the cursor from one window to another, do some editing, jump back to the first window, and be in the same place. A window's notion of your current position (whether or not the cursor is in the window) is called the point . Each window has its own point. It's easy to use the terms point and cursor interchangeably—but we'll try to be specific.

Читать дальше