} catch(Throwable t) {

android.util.Log. e("WeatherPlus",

"Exception in updateForecast()", t);

}

}

Much of this is similar to the equivalent piece of the original Weather demo — perform the HTTP request, convert that into a set of Forecastobjects, and turn those into a Web page. The first difference is that the Web page is simply cached in the service, since the service cannot directly put the page into the activity’s WebView. The second difference is that we call sendBroadcast(), which takes an Intentand sends it out to all interested parties. That Intent is declared up front in the class prologue:

privateIntent broadcast = new Intent(BROADCAST_ACTION);

Here, BROADCAST_ACTIONis simply a static Stringwith a value that will distinguish this Intent from all others:

public static finalString BROADCAST_ACTION =

"com.commonsware.android.service.ForecastUpdateEvent";

Where’s the Remote? And the Rest of the Code?

In Android, services can either be local or remote. Local services run in the same process as the launching activity; remote services run in their own process. A detailed discussion of remote services will be added to a future edition of this book.

We will return to this service in Chapter 33, at which point we will flesh out how locations are tracked (and, in this case, mocked up).

CHAPTER 31

Invoking a Service

Services can be used by any application component that “hangs around” for a reasonable period of time. This includes activities, content providers, and other services. Notably, it does not include pure intent receivers (i.e., intent receivers that are not part of an activity), since those will get garbage collected immediately after each instance processes one incoming Intent.

To use a service, you need to get an instance of the AIDL interface for the service, then call methods on that interface as if it were a local object. When done, you can release the interface, indicating you no longer need the service.

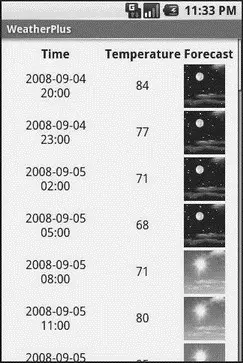

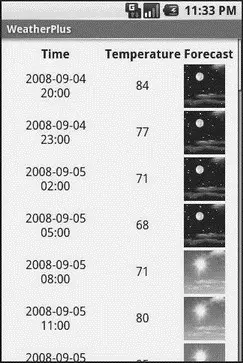

In this chapter, we will look at the client side of the Service/WeatherPlussample application. The WeatherPlusactivity looks an awful lot like the original Weather application — just a Web page showing a weather forecast as you can see in Figure 31-1.

Figure 31-1. The WeatherPlus service client

The difference is that, as the emulator “moves”, the weather forecast changes, based on updates provided by the service.

To use a service, you first need to create an instance of your own ServiceConnectionclass. ServiceConnection, as the name suggests, represents your connection to the service for the purposes of making IPC calls. For example, here is the ServiceConnectionfrom the WeatherPlusclass in the WeatherPlusproject:

privateServiceConnection svcConn = new ServiceConnection() {

publicvoid onServiceConnected(ComponentName className,

IBinder binder) {

service = IWeather.Stub. asInterface(binder);

browser. postDelayed( new Runnable() {

publicvoid run() {

updateForecast();

}

}, 1000);

}

publicvoid onServiceDisconnected(ComponentName className) {

service = null;

}

};

Your ServiceConnectionsubclass needs to implement two methods:

1. onServiceConnected(), which is called once your activity is bound to the service

2. onServiceDisconnected(), which is called if your connection ends normally, such as you unbinding your activity from the service

Each of those methods receives a ComponentName, which simply identifies the service you connected to. More importantly, onServiceConnected()receives an IBinderinstance, which is your gateway to the IPC interface. You will want to convert the IBinderinto an instance of your AIDL interface class, so you can use IPC as if you were calling regular methods on a regular Java class ( IWeather.Stub.asInterface(binder)).

To actually hook your activity to the service, call bindService()on the activity:

bindService(serviceIntent, svcConn, BIND_AUTO_CREATE);

The bindService()method takes three parameters:

1. An Intentrepresenting the service you wish to invoke — for your own service, it’s easiest to use an intent referencing the service class directly ( new Intent(this, WeatherPlusService.class))

2. Your ServiceConnectioninstance

3. A set of flags — most times, you will want to pass in BIND_AUTO_CREATE, which will start up the service if it is not already running

After your bindService()call, your onServiceConnected()callback in the ServiceConnectionwill eventually be invoked, at which time your connection is ready for use.

Once your service interface object is ready ( IWeather.Stub.asInterface(binder)), you can start calling methods on it as you need to. In fact, if you disabled some widgets awaiting the connection, now is a fine time to re-enable them.

However, you will want to trap two exceptions. One is DeadObjectException— if this is raised, your service connection terminated unexpectedly. In this case, you should unwind your use of the service, perhaps by calling onServiceDisconnected()manually, as shown previously. The other is RemoteException, which is a more general-purpose exception indicating a cross-process communications problem. Again, you should probably cease your use of the service.

When you are done with the IPC interface, call unbindService(), passing in the ServiceConnection. Eventually, your connection’s onServiceDisconnected()callback will be invoked, at which point you should null out your interface object, disable relevant widgets, or otherwise flag yourself as no longer being able to use the service.

For example, in the WeatherPlus implementation of onServiceDisconnected()shown previously, we null out the IWeatherservice object.

You can always reconnect to the service, via bindService(), if you need to use it again.

In addition to binding to the service for the purposes of IPC, you can manually start and stop the service. This is particularly useful in cases where you want the service to keep running independently of your activities — otherwise, once you unbind the service, your service could well be closed down.

To start a service, simply call startService(), providing two parameters:

Читать дальше