The search and domain statements are mutually exclusive and may not appear more than once. If neither option is given, the resolver will try to guess the default domain from the local hostname using the getdomainname(2) system call. If the local hostname doesn't have a domain part, the default domain will be assumed to be the root domain.

If you decide to put a search statement into resolv.conf , you should be careful about what domains you add to this list. Resolver libraries prior to BIND 4.9 used to construct a default search list from the domain name when no search list was given. This default list was made up of the default domain itself, plus all of its parent domains up to the root. This caused some problems because DNS requests wound up at name servers that were never meant to see them.

Assume you're at the Virtual Brewery and want to log in to foot.groucho.edu . By a slip of your fingers, you mistype foot as foo , which doesn't exist. GMU's name server will therefore tell you that it knows no such host. With the old-style search list, the resolver would now go on trying the name with vbrew.com and com appended. The latter is problematic because groucho.edu.com might actually be a valid domain name. Their name server might then even find foo in their domain, pointing you to one of their hosts - which clearly was not intended.

For some applications, these bogus host lookups can be a security problem. Therefore, you should usually limit the domains on your search list to your local organization, or something comparable. At the Mathematics department of Groucho Marx University, the search list would commonly be set to maths.groucho.edu and groucho.edu .

If default domains sound confusing to you, consider this sample resolv.conf file for the Virtual Brewery:

# /etc/resolv.conf # Our domain domain vbrew.com # # We use vlager as central name server: name server 172.16.1.1

When resolving the name vale , the resolver looks up vale and, failing this, vale.vbrew.com .

When running a LAN inside a larger network, you definitely should use central name servers if they are available. The name servers develop rich caches that speed up repeat queries, since all queries are forwarded to them. However, this scheme has a drawback: when a fire destroyed the backbone cable at Olaf's university, no more work was possible on his department's LAN because the resolver could no longer reach any of the name servers. This situation caused difficulties with most network services, such as X terminal logins and printing.

Although it is not very common for campus backbones to go down in flames, one might want to take precautions against cases like this.

One option is to set up a local name server that resolves hostnames from your local domain and forwards all queries for other hostnames to the main servers. Of course, this is applicable only if you are running your own domain.

Alternatively, you can maintain a backup host table for your domain or LAN in /etc/hosts . This is very simple to do. You simply ensure that the resolver library queries DNS first, and the hosts file next. In an /etc/host.conf file you'd use " order bind,hosts ", and in an /etc/nsswitch.conf file you'd use " hosts: dns files ", to make the resolver fall back to the hosts file if the central name server is unreachable.

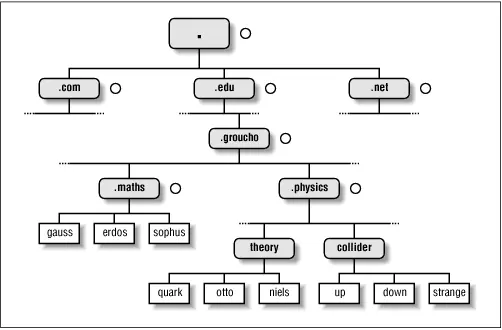

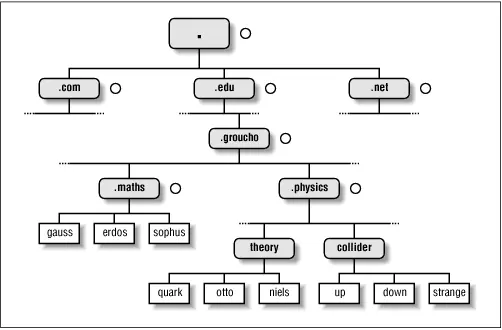

DNS organizes hostnames in a domain hierarchy. A domain is a collection of sites that are related in some sense - because they form a proper network (e.g., all machines on a campus, or all hosts on BITNET), because they all belong to a certain organization (e.g., the U.S. government), or because they're simply geographically close. For instance, universities are commonly grouped in the edu domain, with each university or college using a separate subdomain , below which their hosts are subsumed. Groucho Marx University have the groucho.edu domain, while the LAN of the Mathematics department is assigned maths.groucho.edu . Hosts on the departmental network would have this domain name tacked onto their hostname, so erdos would be known as erdos.maths.groucho.edu . This is called the fully qualified domain name (FQDN), which uniquely identifies this host worldwide.

Figure 6.1 shows a section of the namespace. The entry at the root of this tree, which is denoted by a single dot, is quite appropriately called the root domain and encompasses all other domains. To indicate that a hostname is a fully qualified domain name, rather than a name relative to some (implicit) local domain, it is sometimes written with a trailing dot. This dot signifies that the name's last component is the root domain.

Figure 6.1: A part of the domain namespace

Depending on its location in the name hierarchy, a domain may be called top-level, second-level, or third-level. More levels of subdivision occur, but they are rare. This list details several top-level domains you may see frequently:

| Domain |

Description |

| edu |

(Mostly U.S.) educational institutions like universities. |

| com |

Commercial organizations and companies. |

| org |

Non-commercial organizations. Private UUCP networks are often in this domain. |

| net |

Gateways and other administrative hosts on a network. |

| mil |

U.S. military institutions. |

| gov |

U.S. government institutions. |

| uucp |

Officially, all site names formerly used as UUCP names without domains have been moved to this domain. |

Historically, the first four of these were assigned to the U.S., but recent changes in policy have meant that these domains, named global Top Level Domains (gTLD), are now considered global in nature. Negotiations are currently underway to broaden the range of gTLDs, which may result in increased choice in the future.

Outside the U.S., each country generally uses a top-level domain of its own named after the two-letter country code defined in ISO-3166. Finland, for instance, uses the fi domain; fr is used by France, de by Germany, and au by Australia. Below this top-level domain, each country's NIC is free to organize hostnames in whatever way they want. Australia has second-level domains similar to the international top-level domains, named com.au and edu.au . Other countries, like Germany, don't use this extra level, but have slightly long names that refer directly to the organizations running a particular domain. It's not uncommon to see hostnames like ftp.informatik.uni-erlangen.de . Chalk that up to German efficiency.

Of course, these national domains do not imply that a host below that domain is actually located in that country; it means only that the host has been registered with that country's NIC. A Swedish manufacturer might have a branch in Australia and still have all its hosts registered with the se top-level domain.

Organizing the namespace in a hierarchy of domain names nicely solves the problem of name uniqueness; with DNS, a hostname has to be unique only within its domain to give it a name different from all other hosts worldwide. Furthermore, fully qualified names are easy to remember. Taken by themselves, these are already very good reasons to split up a large domain into several subdomains.

Читать дальше

![Andrew Radford - Linguistics An Introduction [Second Edition]](/books/397851/andrew-radford-linguistics-an-introduction-second-thumb.webp)