Inspire your people to think like entrepreneurs, and whatever you do, treat them like adults. The hardest taskmaster of all is a person’s own conscience, so the more responsibility you give people, the better they will work for you.

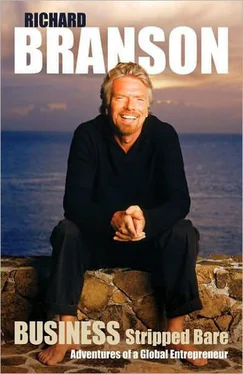

For thirty-five years, the Virgin Group has steered clear of rote mediocrity and steamed full-speed ahead into a world of pleasurable scheming, spiked with the occasional cock-up. The way we have worked has allowed us to live full lives. I can’t give you the formula for this, and you probably wouldn’t follow it anyway. After all, you’re having to respond to the circumstances you’re in, while doing the job that you’re doing. I hope this book will give you some ideas about how you can empower your employees — and empower yourself, come to that. But you really have to find the solutions that work for you.

Here is the good news: the more you free your people to think for themselves, the more they can help you. You don’t have to do this all on your own.

Flying the Flag

When I was sixteen I was approached by a woman called Patricia Lambert who offered me £80,000 to sell Student —the magazine I had started at school —to IPC, now the Trinity Mirror stable of newspapers and magazines based in the UK.

It so happened that I had found a tiny island off Menorca which I was thinking of buying and living on. It was a beautiful place with one very small whitewashed house that had a loo which dropped its waste down the side of a cliff. Living in splendid isolation in the middle of paradise seemed like an attractive proposition at the time because, while our music mail-order business was taking off, running the magazine just got harder and harder. Until I’d sold the advertising I had no regular money to fund the printing and paper costs. It was edge-of-the-seat stuff at first but it had begun to wear me down.

IPC were not only offering me a lot of money; they wanted me to stay on as editor. Student wouldn’t, strictly speaking, be my magazine any more, but I would get to keep a job I still enjoyed doing.

So I decided to accept, and I went along to lunch at IPC in Holborn, just off Fleet Street. They had all the directors around the table. And once we had shaken hands on the deal, I started to talk about my vision. I told the directors I wanted to set up Student holidays, a Student travel agency, Student record shops, Student health clubs — even a Student airline? I could see eyebrows being raised. After the lunch I got a call thanking me for coming — but the directors had changed their minds about the investment, cancelling the plan to buy my magazine. They were far too courteous to say so, but the writing was on the wall: they thought I was mad.

Many years later Patricia was good enough to write me a delightful letter telling me just how much they had been kicking themselves over the years as they watched Virgin stir up sector after sector, almost exactly as their young would-be magazine editor had predicted.

I suspect they were right in not dealing with me. IPC were and are in the publishing business. They are publishers. They know who they are, and they didn’t need some kid, however promising, telling them all the other things they could be. The last thing they wanted was a wasp in the room, batting itself against their windows and getting more and more frustrated, and that, surely, is what I would have become.

Most businesses concentrate on one thing, and for the best of reasons: because their founders and leaders care about one thing, above all others, and they want to devote their lives to that thing. They’re not limited in their thinking. They’re focused.

The conventional wisdom at business school is that you stick with what you know. Of the top twenty brands in the world, nineteen ply a well-defined trade. Coca-Cola specialises in soft drinks, Microsoft’s into computers, Nike makes sports shoes and gear.

The exception in this list is Virgin — and the fact that we’re worth several billion dollars and counting really gets up the noses of people who think they know ‘the rules of business’ (whatever they are).

We’re the only one of the top twenty that has diversified into a range of business activities, including airlines, trains, holidays, mobile phones, media — including television, radio and cable — the Internet, financial services and healthcare. And believe me when I say this really upsets people. I remember in July 1997 London’s Evening Standard covered our advance into America with an article headlined ‘WHEN BRAND STRETCHING STRETCHES CREDIBILITY’.

I think this says more about the business community generally than it says about Virgin. How far must we fly before pundits of one sort or another stop predicting our fiery descent? Our proposition isn’t hard to understand: we offer our customers a Virgin experience, and we make sure that this Virgin experience is a substantial and consistent one, across all sectors of our business . Far from ‘slapping our brand name’ on a number of products, we carefully research the Achilles heels of different global industries, and only when we feel we can potentially turn an industry on its head, and fulfil our key role as the consumer’s champion, do we move in on it. The financial services industry is an eloquent example. In three years, Virgin Direct acquired 200,000 investors and was managing £1.6 billion. As a result of its entry into the market, much of the rest of the industry brought their charges down too to compete.

Incredibly or not, Virgin has thrived by weaving its magic through many seemingly unrelated sectors. Between 2000 and 2003, Virgin created three new billion-dollar companies from scratch, in three different countries. Virgin Blue in Australia took 35 per cent of the aviation market and reduced fares dramatically. Virgin Mobile became the UK’s fastest growing network. Virgin Mobile in America was America’s fastest ever growing company, private or public. Our revenue per employee — $902,000 — is the best in the world, and we’ve got the highest customer satisfaction record too, with 95 per cent of our five million customers recommending us to a friend. Over the last thirty-five years we at Virgin have created more billion-dollar companies in more sectors than any other company.

And right now, as everyone is battening down the hatches and preparing for the twenty-first century’s first really big global recession, Virgin turns out to be ready for the storm as well. Because its risks are spread, the failure of one part — even a major part — will not ruin the whole. (Imagine if we hadn’t diversified and if we had just stuck with the record and music industry, which today faces huge challenges because of the digital download revolution — we might well have disappeared!)

So here’s the question: if Virgin has more fun when times are good, and weathers well when times are bad, why doesn’t every company try to ‘do a Virgin’? And why are the business teachers still telling young entrepreneurs to stick to what they know?

Well, I think the business teachers are right . You should focus on what you know. You should also focus on what gets you up in the morning. And for most people, that means you should focus on one core business.

The odd thing about Virgin — and this is what people often have difficulty with — is that Virgin’s particular focus made it absolutely imperative that it diversified into many businesses. Contrary to appearances, Virgin is as focused as any great company. Its oddness comes from what it focuses on . We might have hit upon the exception that proves the rule: our customers and investors relate to us more as an idea or philosophy than as a company.

Читать дальше