Mistakes such as Apple’s decision to limit the sale of its operating-system software for its own hardware will be repeated often in the years ahead. Some telephone and cable companies are already talking about communicating only with the software they control.

1984: the Apple macintosh computer

It’s increasingly important to be able to compete and cooperate at the same time, but that calls for a lot of maturity.

The separation of hardware and software was a major issue in the collaboration between IBM and Microsoft to create OS/2. The separation of hardware and software standards is still an issue today. Software standards create a level playing field for the hardware companies, but many manufacturers use the tie between their hardware and their software to distinguish their systems. Some companies treat hardware and software as separate businesses and some don’t. These different approaches will be played out again on the highway.

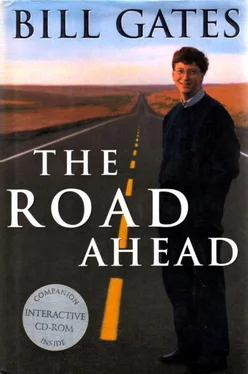

Throughout the 1980s, IBM was awesome by every measure capitalism knows. In 1984, it set the record for the most money ever made by any firm in a single year—$6.6 billion of profit. In that banner year IBM introduced its second-generation personal computer, a high-performance machine called the PC AT, which incorporated Intel’s 80286 microprocessor (colloquially known as the “286"). It was three times faster than the original IBM PC. The AT was a great success, and within a year had more than 70 percent of all business PC sales.

When IBM launched the original PC, it never expected the machine to challenge sales of the company’s business systems, although a significant percentage of the PCs were bought by IBM’s traditional customers. Company executives thought the smaller machines would find their place only at the low end of the market. As PCs became more powerful, to avoid having them cannibalize its higher-end products, IBM held back on PC development.

In its mainframe business, IBM had always been able to control the adoption of new standards. For example, the company would limit the price/performance of a new line of hardware so it wouldn’t steal business from existing, more expensive products. It would encourage the adoption of new versions of its operating systems by releasing hardware that required the new software or vice versa. That kind of strategy might have worked well for mainframes, but it was a disaster in the fast-moving personal-computer market. IBM could still command somewhat higher prices for equivalent performance, but the world had discovered that lots of companies made compatible hardware, and that if IBM couldn’t deliver the right value, someone else would.

Three engineers who appreciated the potential offered by IBM’s entry into the personal-computer business left their jobs at Texas Instruments and formed a new company—Compaq Computer. They built hardware that would accept the same accessory cards as the IBM PC and licensed MS-DOS so their computers were able to run the same applications as the IBM PC. The company produced machines that did everything the IBM PCs did and were more portable. Compaq quickly became one of the all-time success stories in American business, selling more than $100 million worth of computers its first year in business. IBM was able to collect royalties by licensing its patent portfolio, but its share of market declined as compatible systems came to market and IBM’s hardware was not competitive.

The company delayed the release of its PCs with the powerful Intel 386 chip, Intel’s successor to the 286. This was done to protect the sales of its low-end minicomputers, which weren’t much more powerful than a 386-based PC. IBM’s delay allowed Compaq to become the first company to introduce a 386-based computer in 1986. This gave Compaq an aura of prestige and leadership that previously had been IBM’s alone.

IBM planned to recover with a one-two punch, the first in hardware and the second in software. It wanted to build computers and write operating systems, each of which would depend exclusively on the other for its new features so competitors would either be frozen out or forced to pay hefty licensing fees. The strategy was to make everyone else’s “IBM-compatible” personal computer obsolete.

The IBM strategy included some good ideas. One was to simplify the design of the PC by taking many applications that had formerly been selectable options and building them into the machine. This would both reduce costs and increase the percentage of IBM components in the ultimate sale. The plan also called for substantial changes in the hardware architecture: new connectors and standards for accessory cards, keyboards, mice, and even displays. To give itself a further advantage IBM didn’t release specifications on any of these connectors until it had shipped the first systems. This was supposed to redefine compatibility standards. Other PC manufacturers and the makers of peripherals would have to start over—IBM would have the lead again.

By 1984, a significant part of Microsoft’s business was providing MS-DOS to manufacturers that built PCs compatible with IBM’s systems. We began working with IBM on a replacement for MS-DOS, eventually named OS/2. Our agreement allowed Microsoft to sell other manufacturers the same operating system that IBM was shipping with its machines. We each were allowed to extend the operating system beyond what we developed together. This time it wasn’t like when we did MS-DOS. IBM wanted to control the standard to help its PC hardware and mainframe businesses. IBM became directly involved in the design and implementation of OS/2.

OS/2 was central to IBM’s corporate software plans. It was to be the first implementation of IBM’s Systems Application Architecture, which the company ultimately intended to have as a common development environment across its full line of computers from mainframe to midrange to PC. IBM executives believed that using the company’s mainframe technology on the PC would prove irresistible to corporate customers who were moving more and more capabilities from mainframe and mini-computers to PCs. They also thought that it would give IBM a huge advantage over PC competitors who would not have access to mainframe technology. IBM’s proprietary extensions of OS/2—called Extended Edition—included communications and database services. And it planned to build a full set of office applications—to be called OfficeVision—to work on top of Extended Edition. The plan predicted these applications, including word processing, would allow IBM to become a major player in PC-application software, and compete with Lotus and WordPerfect. The development of OfficeVision required another team of thousands. OS/2 was not just an operating system, it was part of a corporate crusade.

The development work was burdened by demands that the project meet a variety of conflicting feature requirements as well as by IBM’s schedule commitments for Extended Edition and OfficeVision. Microsoft went ahead and developed OS/2 applications to help get the market going, but as time went on, our confidence in OS/2 eroded. We had entered into the project with the belief that IBM would allow OS/2 to be enough like Windows that a software developer would have to make at most only minor modifications to get an application running on both platforms. But after IBM’s insistence that the applications be compatible with its mainframe and midrange systems, what we were left with was more like an unwieldy mainframe operating system than a PC one.

Our business relationship with IBM was vital to us. That year, 1986, we had taken Microsoft public to provide liquidity for the employees who had been given stock options. It was about that time Steve Ballmer and I proposed to IBM that they buy up to 30 percent of Microsoft—at a bargain price—so it would share in our fortune, good or bad. We thought this might help the companies work together more amicably and productively. IBM was not interested.

Читать дальше