The IBM standard became the platform everybody imitated. A lot of the reason was timing and its use of a 16-bit processor. Both timing and marketing are key to acceptance with technology products. The PC happened to be a good machine, but another company could have set the standard by getting enough desirable applications and selling enough machines.

IBM’s early business decisions, caused by its rush to get the PCs out, made it very easy for other companies to build compatible machines. The architecture was for sale. The microprocessor chips from Intel and Microsoft’s operating system were available. This openness was a powerful incentive for component builders, software developers, and everyone else in the business to try to copy.

Within three years almost all the competing standards for personal computers disappeared. The only exceptions were Apple’s Apple II and Macintosh. Hewlett Packard, DEC, Texas Instruments, and Xerox, despite their technologies, reputations, and customer bases, failed in the personal-computer market in the early 1980s because their machines weren’t compatible and didn’t offer significant enough improvements over the IBM architecture. A host of start-ups, such as Eagle and Northstar, thought people would buy their hardware because it offered something different and slightly better than the IBM PC. All of the start-ups either changed to building compatible hardware or failed. The IBM PC became the hardware standard. By the mid-1980s, there were dozens of IBM-compatible PCs. Although buyers of a PC might not have articulated it this way, what they were looking for was the hardware that ran the most software, and they wanted the same system the people they knew and worked with had.

It has become popular for certain revisionist historians to conclude that IBM made a mistake working with Intel and Microsoft to create its PC. They argue that IBM should have kept the PC architecture proprietary, and that Intel and Microsoft somehow got the better of IBM. But the revisionists are missing the point. IBM became the central force in the PC industry precisely because it was able to harness an incredible amount of innovative talent and entrepreneurial energy and use it to promote its open architecture. IBM set the standards.

In the mainframe business IBM was king of the hill, and competitors found it hard to match the IBM sales force and high R&D. If a competitor tried climbing the hill, IBM could focus its assets to make the ascent nearly impossible. But in the volatile world of the personal computer, IBM’s position was more like that of the leading runner in a marathon. As long as the leader keeps running as fast or faster than the others, he stays in the lead and competitors will have to keep trying to catch up. If, however, he slacks off or stops pushing himself, the rest will pass him by. There weren’t many deterrents to the other racers, as would soon become clear.

By 1983, I thought our next step should be to develop a graphical operating system. I didn’t believe we would be able to retain our position at the forefront of the software industry if we stuck with MS-DOS, because MS-DOS was character-based. A user had to type in often-obscure commands, which then appeared on the screen. MS-DOS didn’t provide pictures and other graphics to help users with applications. The interface is the way the computer and the user communicate. I believed that in the future interfaces would be graphical and that it was essential for Microsoft to move beyond MS-DOS and set a new standard in which pictures and fonts (typefaces) would be part of an easier-to-use interface. In order to realize our vision, PCs had to be made easier to use not only to help existing customers, but also to attract new ones who wouldn’t take the time to learn to work with a complicated interface.

To illustrate the huge difference between a character-based computer program and a graphical one, imagine playing a board game such as chess, checkers, Go, or Monopoly on a computer screen. With a character-based system, you type in your moves using characters. You write “Move the piece on square 11 to square 19” or something slightly more cryptic like “Pawn to QB3.” But in a graphical computer system, you see the board game on your screen. You move pieces by pointing at them and actually dragging them to their new locations.

Researchers at Xerox’s now-famous Palo Alto Research Center in California explored new paradigms for human-computer interaction. They showed that it was easier to instruct a computer if you could point at things on the screen and see pictures. They used a device called a “mouse,” which could be rolled on a tabletop to move a pointer around on the screen. Xerox did a poor job of taking commercial advantage of this groundbreaking idea, because its machines were expensive and didn’t use standard microprocessors. Getting great research to translate into products that sell is still a big problem for many companies.

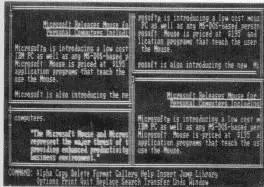

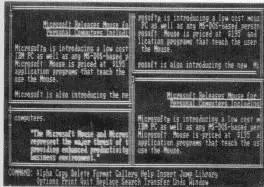

1984: Character user interface in an early version of Microsoft Word for DOS

In 1983, Microsoft announced that we planned to bring graphical computing to the IBM PC, with a product called Windows. Our goal was to create software that would extend MS-DOS and let people use a mouse, employ graphical images on the computer screen, and make available on the screen a number of “windows,” each running a different computer program. At that time two of the personal computers on the market had graphical capabilities: the Xerox Star and the Apple Lisa. Both were expensive, limited in capability, and built on proprietary hardware architectures. Other hardware companies couldn’t license the operating systems to build compatible systems, and neither computer attracted many software companies to develop applications. Microsoft wanted to create an open standard and bring graphical capabilities to any computer that was running MS-DOS.

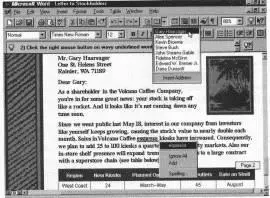

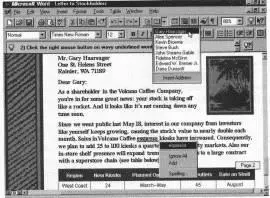

1995: Graphical user interface in Microsoft Word for Windows

The first popular graphical platform came to market in 1984, when Apple released its Macintosh. Everything about the Macintosh’s proprietary operating system was graphical, and it was an enormous success. The initial hardware and operating-system software Apple released were quite limited but vividly demonstrated the potential of the graphical interface. As the hardware and software improved, the potential was realized.

We worked closely with Apple throughout the development of the Macintosh. Steve Jobs led the Macintosh team. Working with him was really fun. Steve has an amazing intuition for engineering and design as well as an ability to motivate people that is world class.

It took a lot of imagination to develop graphical computer programs. What should one look like? How should it behave? Some ideas were inherited from the work done at Xerox and some were original. At first we went to excess with the possibilities. We used nearly every one of the fonts and icons we could. Then we figured out all that made it hard to look at and changed to more sober menus. We created a word processor, Microsoft Word, and a spreadsheet, Microsoft Excel, for the Macintosh. These were Microsoft’s first graphical products.

The Macintosh had great system software, but Apple refused (until 1995) to let anyone else make computer hardware that would run it. This was traditional hardware-company thinking: If you wanted the software, you had to buy Apple computers. Microsoft wanted the Macintosh to sell well and be widely accepted, not only because we had invested a lot in creating applications for it, but also because we wanted the public to accept graphical computing.

Читать дальше