He saw it then.

THE STRANGEST POSSIBILITYtrip-trapped over the surface of Minerva’s brain once the game had started. She thought: What if God or Buddha or the Creator or who-the-fuck-ever had come to her as a freshly conceived zygote; what if the Creator had said: Listen, you, this is how your life is going to unspool. Dead father, dead brother, sadness and rage and regret aplenty, and the whole shebang’s gonna end on the far side of the desert with some unearthly creature making you answer riddles. Knowing all this, chum, you sure you want to ride this merry-go-round?

What would she have said, knowing the shape of her life to come?

“ If it is information you seek, come and see me. If it is pairs of letters you need, I have consecutively three. ”

The thing chanted this riddle in Cort’s voice. She had always gotten an F in classes where deductive reasoning was taught. That stuff maddened her. When would she ever need to know What has four eyes but can’t see? or What has hands but can’t clap?

The thing licked its lips. Its corrugated black tongue slipped out, sopping up the drool that threatened to cascade down its chin. Its body trembled with tension, although its eyes remained dull and dead.

Far off: the sound of trees snapping.

“Please,” it said. “An answer.”

“Give me a few minutes. Isn’t that fair?”

“ Fair has very little to do with it, Minny ,” the thing said in Cort’s voice.

Minerva’s brain synapses burned up, smoke practically pouring out her ears. If it is pairs of letters you need, I have consecutively three. She pictured six envelopes, six stamps, six addresses, all in a neat row. If it is information you seek… The letters held important information, but she couldn’t open them. Each envelope was fastened shut. Goddamn it, open !

The tree-snap sounds grew louder. A new sound joined those snaps: a low rumble. The creature must have heard it, too.

“Tick-tock,” it said in its own voice.

Minerva squeezed her eyes shut. Information you seek… pairs of letters…

She laughed mirthlessly. “I never was any good at these.”

The thing chuckled. “ Should have paid more attention in school, big sis. ”

Minerva gave it a sunless smile. “Fuck off. Stop talking like that.”

“You have fire,” it said, no longer in Cort’s voice. “I like that. It will take time to extinguish.”

The rumble was unmistakable now. The sand trembled under Minerva. The creature unkinked its legs and stood. It towered over her, its limbs throwing shadows across her face.

The rumble became the metallic rattle of an engine. A pair of headlights burnt through the trees. The thing’s attention was diverted. She took that chance to skitter away.

Some kind of vehicle bore down on them. The driver blared the horn. The thing took a step back, its perplexity deepening. Was it some kind of… tank? A figure stood on its hood. A familiar English voice rose over the churn of the engine.

“ Git aloooong, little dooooogies… ”

The thing lifted one arm, a spindly finger pointing.

“Father—?” it said questioningly.

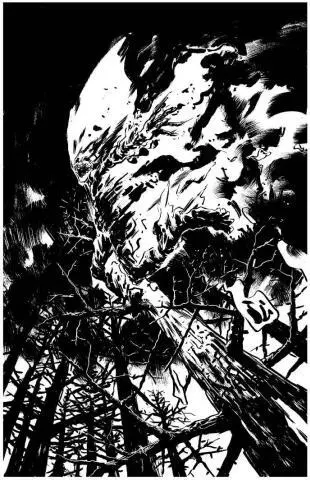

A concentrated stream of fire ripped through the night. It hit the thing square in the chest. Ebenezer’s face was lit by the glow off the igniting gasoline. The creature went up like a kindling effigy. Illuminated by the brilliant light, its face held an expression of puzzled wonderment. Then it began to scream. A high trilling shriek that ascended through several octaves before dropping to a searing howl. It gibbered in many voices, a few of them recognizable to Minerva.

Ebenezer let his finger off the flamethrower. The thing stood in a flickering column of orange, crackling and hissing. It craned its head toward Minerva; its eyes were unchanged, black as lumps of coal in the melting tapestry of its face. The fire had peeled its mouth even wider. It issued a mocking titter and began to jig in place, its legs kicking crazily, flinging gobbets of roasting skin from its shanks.

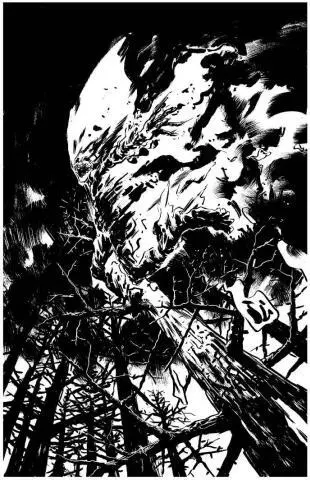

It took two steps toward Ebenezer. He let loose with another burst. The thing shrieked in what seemed to be true pain. Then it fled down the slope toward the forest. A mesmerizing sight: its fiery limbs carrying it swiftly through the night, twenty yards in a single stride. It reached the woods and monkeyed up the first tree, then began to leap from treetop to treetop. It left a point of flame at the tip of each fir; the trees began to burn, the fire spreading rapidly.

Minerva approached the machine. Eb remained on the hood, a nitrous blue finger dancing from the nozzle of the flamethrower. Ellen was driving. Nate was there, too.

“The cavalry has arrived,” Ebenezer said grandly.

Minerva grinned. She couldn’t help herself.

“Ah!” Eb said. “Finally, a smile! What was that god-awful thing?”

“That was what took the kids,” Ellen said to Eb.

“Ah-ha!” Ebenezer said, full of overadrenalized good cheer. “Mystery solved!”

Minerva pointed at the cleft. “They’re in there. The children are.”

“We better go find them,” said Ellen.

“Oh, I don’t think you want to do that,” Minerva whispered.

MICAH SHUGHRUEknew it wasn’t the Reverend. But the man’s face was familiar.

Even by the most charitable definition, this could not be considered a man anymore. He hung in the center of the box buried deep within the black rock. He was suspended on a network of red ropes resembling wet sinews; the ropes were attached to various points of the man’s anatomy but primarily his shoulders and head and neck, bearing him aloft. The ropes issued a faint thrum like high-tension power lines.

This man was grotesquely shriveled, and human only insofar as he had a pair of driftwood legs and arms that were no more than bones clad in the barest stretching of tissue. His chest was so withered that the skin had shrunk around every rib, his innards encased in a yellowish sack in the center of the rib cage. His head was a grinning, fleshless skull, nose a blade of cartilage. His legs were pulled up tight to his body, the kneecaps visible as saucers, the bones of his feet jutting like gruesome sticks. His posture was that of a sickening fetus curled up in its womb.

The flashlight beam hung on its terrible face for an instant. As wasted as it was, Micah had seen it before. But where? Something in the flinty slope of those cheeks, the jut of those calcified ears…

It finally registered. He’d seen this man’s portrait on a desk in the Preston School for Boys. It was Augustus Preston himself.

Preston’s appearance encouraged a gruesome fixation. Much as he wanted to, Micah could not look away. It was as if the man had been devoured from the inside out, the way termites remorselessly harvest an oak tree. If Micah were to touch him the wrong way, he was certain Preston’s innards would spill out—parched, desiccated, sawdusty: his lungs and liver and heart all pulverized and turned to powder. And still, the annihilations of the man’s soul seemed somehow worse, if less obvious, than the ruin of his body. There was nothing inside him anymore. This was Micah’s dread sense. Not even sawdust. Only a yellowing, howling emptiness that his soul had fled years ago. The essence of his humanity had been irretrievably lost, boiled away like steam off a hot pan.

How had Preston arrived at this place? How many years had he been hanging here? For nearly a century —was that in any way possible? What were those ropes? What was the purpose of this vault and—

Читать дальше