He walked backward to the vestry, still facing the pews. He took it all in. His flock—the deceitful scabs, the filthy betrayers—were dying in wretched agony, coughing up scraps of their guts as their children lay on the floor insensate or still clinging to their parents as they expired.

God’s will be done , he thought with tremendous satisfaction.

Another man was tottering down the aisle toward him. His face was plastered with blood to the point that Amos could no longer identify him. Earl the Pearl, is that you? Why the long face, Earl? Oho-o- ho ! Amos backed into the vestry and locked the door. He turned and saw Virgil sitting in the corner, shivering. Amos grimaced. He hoped the blubbering clod could hold it together until his usefulness dried up.

Amos crossed to his desk and removed the claw hammer stashed in the drawer. Somebody hit the vestry door.

“Earl the Pearl, don’t interrupt!” Amos said, and hooted laughter. “Can’t you see I’m busy in here? Make an appointment with my secretary!”

A pair of fists pounding… but as the seconds drew on, their force ebbed. Soon nothing but a kittenish scratching could be heard from the other side of the door.

FIRST, NATE HEARD THE SCREAMS.Then the gunshot.

He was outside the bunkhouse with Ellen. They had watched everyone file into the chapel. Soon after, they heard the Reverend sermonizing. Nate pictured everyone inside, eyes closed and swaying. Things might turn out okay, he thought. Maybe God really was watching over them again.

Shortly after that the screaming had started. Ellen went stiff. She grabbed Nate’s hand. The shrieks inside the chapel ascended to a shrill peak and stayed there. Next came the loud bang . Nate wouldn’t have been sure a year ago, but by now he’d heard enough gunshots at Little Heaven to know that sound.

“No” was all Ellen said.

They stood in the chilly night with the woods silent beyond the fence. Who was doing the shooting? His father was in there. And the Conkwrights, whom Nate liked a whole bunch. And some others he guessed were decent enough.

Neither Nate nor Ellen moved. Nate’s legs were locked up—someone might as well have bolted his knees together. Clearly something horrible was happening. Could he help? He yanked his hand away from Ellen’s—“Nate!” she cried out—and stole toward the chapel.

He crossed the square as if in a dream; the momentum was sickening, unstoppable. The screams intensified, pulsing against his eardrums. As he got closer, he heard other noises: choking, wheezing.

He crept around the side of the chapel. The blood pounding in his skull made him dizzy. He had to brace himself on the wall so he didn’t faint. A terrible pressure inside his head pushed against his eyeballs and nose so hard that he had to breathe through his mouth, which had gone dry, his lips glued together with pasty spit. He curled his fingers over the windowsill and peeked inside.

WHEN AMOS OPENEDthe vestry door again, a blood-slick body slumped forward to hit his shoes. Amos roughly kicked it aside and passed down the aisle, pistol in one hand and hammer in the other.

A strange light had entered his eyes. A mincing, eager refraction that had lain dormant for his whole life, really, apart from a few brief and secretive incidents where it had been allowed to glow brightly. There was nothing to stop it now. That light was free to stoke itself into a gleeful inferno.

He high-stepped down the aisle over the twitching bodies of his worshippers. A few of the older children were still conscious, beating their fists weakly against the doors. The younger ones were already insensate.

A hand manacled around his ankle. Amos followed it to the body of Nell Conkwright, the rancid sow, lying facedown next to her unconscious daughter. The flesh of her fingertips had been eaten away by the acidic vomit she’d hacked up. She was mumbling something. A prayer, a curse—who cared? Amos shook his ankle free in disgust. Then he set his foot on her shoulder and shoved her onto her back. Her eyes were milky, flecks of bloody vomit smeared on her face. Her skin sizzled as the drain cleaner continued to eat into it. She kept mumbling even though most of her teeth had fallen out, her gums stripped back to the bone, her mouth sagging inward like an old pumpkin left to rot on a front stoop.

“O ye of little faith,” Amos whispered. “You did this to yourself, heathen. And to your child, too.”

The woman’s face wrenched into an expression Amos took as mortal terror. She reached blindly for her daughter. Amos raised the hammer and brought it down on her skull. He’d never hit someone with a hammer, so he didn’t know how hard he ought to do it—as hard as possible seemed wisest, but at the last instant he quailed, so the hammer impacted Nell Conkwright’s head with a flat smack , taking away a coin-sized blot of skin. She moaned and retched again. Amos gritted his teeth and flipped the hammer around to the claw end and brought it down again much harder. It punched through the top of Nell Conkwright’s head. Success! Now she thrashed and yowled; Amos felt the thrum of her body all the way up the hammer’s wooden shaft. He wrenched the claw free and continued on. He did not notice the horrified face of Reggie Longpre’s boy hovering at the window.

Movement to his left. He marked someone crawling toward the doors. He expected it to be Bart Kennick or Shane Weagel, who were among Little Heaven’s hardiest specimens—but land sakes alive, if it wasn’t Reginald Longpre. Reggie was near the exit on his bloody hands and knees. Saying something, too, though it came out all mush-mouthed. Nate, I’m sorry , it sounded like.

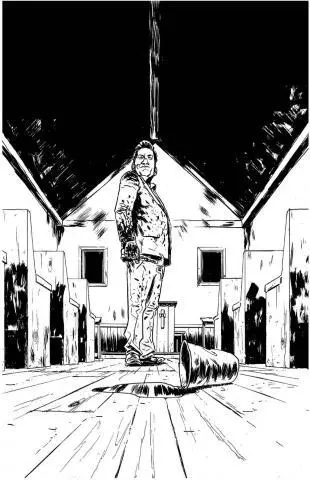

Amos stepped over a half dozen bodies as if they were sandbags, making his way to the front. Only one boy was trying to open the doors now; Amos tucked the hammer under his armpit and cupped his hand over the boy’s face and pushed hard; the boy groaned and fell, curling into a fetal ball. Amos unlocked the doors and threw them open with a flourish.

“Monsieur,” he remarked to Reggie, “you look as if you could use some fresh air.”

Reggie crawled past Amos, perhaps not even cognizant he was there. Amos took no offense at this, seeing as Reggie was likely blind from the cleaner burns. Sturdy ole Reg made it all the way out the doors, struggling down the swaybacked steps onto the trampled grass. His palms slipped, and he sprawled on his belly. He wormed around on the ground; the sight filled Amos with revulsion. He stepped forward, set his foot firmly on the back of Reggie’s neck, and shoved him down into the dirt. Then he cocked the pistol and—

ELLEN WATCHED THE CHAPEL DOORSswing open. She caught a brief glimpse of the insides—bodies lying on the ground or slumped over the pews—before her attention was stolen by the sight of her sister’s ex crawling out the doors. By the light streaming out of the chapel, she could see that Reggie was covered from head to toe in gore. He squirmed awkwardly, chest heaving, strings of bloody drool swaying from his lips. He clawed his way down the steps and made it a few more feet before collapsing.

The Reverend followed Reggie out. He walked with a purpose, seemingly unhurt. He held something in each hand. Ellen watched, awestruck with horror, as the Reverend stomped on the back of Reggie’s neck, forcing a sad bleat out of the servile mailman, then cocked the pistol in his right hand and fired it point-blank at Reggie’s head.

The gun issued a sharp crack. The feathery fringe of hair at the back of Reggie’s head—it must have been months since his last haircut—puffed up as the slug drilled into his skull. Reggie grunted softly, as if in mild disagreement with something the Reverend had said. The bullet corkscrewed through his head and made its exit above his wide gaping eyes, blowing a window of bone out of his forehead. It looks like the box the little bird pops out of in a cuckoo clock , Ellen thought in a daze of fright.

Читать дальше