Amos stopped before the window. Night had drawn down on Little Heaven, but the security lamps burned. He stared at his church, topped with that mighty crucifix.

He stood, transfixed, listening to the Voice.

It came to Amos every night. God’s Voice—whom else could it belong to? He let it settle into his bones, soothing him. The Voice had already warned there would come a dissent. Amos had known this before the first fence post went up at Little Heaven. It was why he had hired Cyril and Virgil, whose acquaintance had been made through unsavory but needful methods.

Any flock could stray, despite the best efforts of its shepherd. That was why a smart shepherd trained a few ill-tempered dogs to keep the sheep in line.

He would weather this storm. He would cast out the irritants and prevail. He must . God had a plan for him. He felt it gathering in the deepest recesses of his mind: that other voice whispering to him, using words he could not make out. A low continuous drone like the massing of flies over rotted offal. The Lord works in mysterious ways.

He retreated to his bed, where he lay stiff as a rod. Without being aware of it, he began to knead his groin. He opened the night table and pulled out the long sharp pin that lay beside his Bible.

Release , he thought. By God, release.

EBENEZER COULD NOT SLEEPhis second night at Little Heaven. His blankets itched, as did his ankle while it healed. He rolled off the cot and pulled on his trousers and one boot. The others were still sleeping. He hobbled out the door.

The night was cool. Combers of ground fog rolled across the square. It flooded over his legs, so thick he could barely see his own feet. A flashlight snapped on behind him.

“What are you doing?”

He turned. Minerva was pointing the light directly at his face. “Lower it,” he said.

She snapped it off. Folded her arms against the chill. She beheld him the way she always did—as if picturing how his head might look on the end of a sharp stick.

He was fairly certain she hated him. That was not so odd in itself—Eb had repulsed plenty of women over his lifetime—but there was no legitimacy to her loathing. On their first encounter she had tried to kill him as a matter of business. That he could understand and even approve. Why, then, throughout their acquaintanceship, had her hatred not slackened? It wasn’t the color of his skin. Eb could sniff a racist at twenty yards. It wasn’t his Englishness, either. So what, then?

“I was going to pick posies for you,” he said. “On account of you being so peachy keen.”

“Oh yeah?” She spat in the dirt. “Drop dead in a shed, Fred.”

“Dive off a cliff, Biff,” he shot right back.

Little Heaven was silent. The only light came from the security lamps strung round the perimeter. The fog hung thickly between the first cut of pines. It swirled in odd patterns, as if at the beck of forces Ebenezer was not attuned to.

They heard it then. Ringing, singsong. The laughter of a child.

They moved toward it, Minerva walking and Eb limping. Ebenezer didn’t want to take another step—the laughter had developed a throaty undertone he didn’t much care for—but his feet would not obey him. He kept gimping on, vaguely horrified at his inability to stop. Minerva’s flashlight shone on the ground in front of them. Nobody else was awake. The compound was at rest. It was just them, alone.

The sound was coming from behind the chapel. The shadows were heaviest there, as the chapel lay at the edge of the compound facing the trees. The flashlight illuminated its rough boards, the paint beginning to flake. The laughter hummed against Ebenezer’s ears like the beat of tiny wings.

“Hello?” Minerva said.

The laughter stopped. In its place was a dry crackly noise that made Ebenezer picture wet seashells, thousands of them, tumbling over one another.

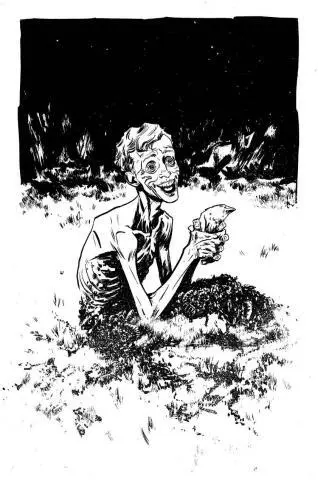

They rounded the side of the chapel that faced the woods. A shape hunched under the silhouette of the crucifix. The fog was hugged tight to it.

“Who’s there?” Ebenezer said.

The flashlight beam jittered toward the shape; Eb got the sense Minerva was reluctant to illuminate this thing, whatever it was. The light crept over the chapel wall and down, falling on the head of the figure sitting there. The fog peeled back, divulging more and more of its body—

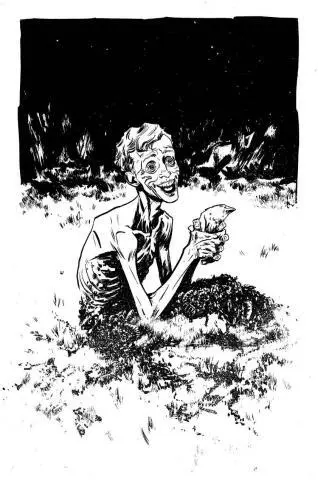

A boy. He sat facing away from them. The mist still clung to his lower half. He was doing something with his hands. The dry, chittery sound was quite powerful now. Ebenezer had no clue what was making it, but the noise itself was enough to sour the spit in his mouth.

They approached the boy, who seemed to have taken no note of them. Fifteen feet, ten feet… the boy turned. He was naked from the waist up. His ribs protruded. His clavicles jutted like beaks. His flesh was white as soap. His eyes were gray. The color of a slug.

Minerva stumbled back and bumped into Ebenezer. He felt the beat of her heart through her clothes—it was hammering hard enough to rattle her entire frame.

The boy smiled. He was bucktoothed—teeth like elephant toes. His slug eyes seemed to pin them both, though lacking pupils it was hard to tell for sure.

The shucking, chittery sounds intensified…

The boy held a dead bird in his hands. The bird’s eyes were the same as the boy’s. He stroked it tenderly. His demeanor was quiet and content, as if he had been found playing with his Matchbox cars in his bedroom.

There was something the matter with one of his hands. The skin seemed to have melted or calcified or fused, the fingers welded into a solid scoop of flesh. He stroked the bird with it, lovingly so. Later, Ebenezer wouldn’t be sure he had seen any of this—there was a vacancy in his memory, a dark sucking hole where something dirty had been buried.

The mist rolled away from the boy’s lower half, the white wisps trailing off to reveal a bristling carpet of perpetual industry.

Bugs. Bark beetles and cockroaches and God knew what else. Millions of bugs covered the boy to his waist. They surged around his hips, antennae waving, crawling over and around one another the way insects do—a way that humans never could, because that mindless proximity of bodies would drive any person mad. They flooded around the boy’s legs, fanning out in a ten-foot circle. Most of their bodies were the brown of a blood blister, but some were a larval albino white. They massed in a pattern that seemed random, but if you looked closely, their movements appeared to have some spirit of organization.

Minerva turned to Ebenezer, her eyes bulging in horror. Ebenezer was barely able to stifle a scream himself—when was the last time he’d screamed in abject fright? As a child, surely, at the prospect of the boogeyman lurking under his bed.

The boy beheld them with those horrid, soul-shriveling eyes and said, “I am so happy to be back home.”

THE NEXT MORNING,Brother Charlie Fairweather showed up at their bunkhouse.

“Mind if I come in?”

Micah was still trying to piece together the events of the past night. He’d heard Eb get up, and Minny after him. He hadn’t made much of it when they both stepped outside—Minny wouldn’t make her move now, he knew, so the most she’d do was jaw at him a little.

Minutes later, there was a big commotion. Had Micah misjudged it—had she tried to flatline Ebenezer? It would have to count as strange timing, but Minerva was an odd woman. But then he’d heard the Reverend yelling: “Cyril! CYRIL! ”

Читать дальше