The fourth day was Mardi Gras, Fat Tuesday. On their return from work, Janice and Judy discovered that Daddy had managed to free his tongue of the knife—by the simple expedient of pulling his tongue into his mouth, allowing the knife to sever it. He had spat blood over his chest and abdomen for hours. Judy sprayed Daddy’s face with D-Con bug killer until he was blinded. Then she cut five notches in his right ear with her cuticle scissors.

On the fifth day, Janice and Judy discovered that Daddy had once again soiled the bed linen. This may well have been surprising to them, considering that Daddy had had nothing to eat in those five days and that the only thing he’d drunk was the blood that flowed from his severed tongue and the urine Judy squeezed into his mouth from the wet sheets.

“This is the last straw,” Janice told Judy.

“I caint hardly blame you for being mad at him,” Judy commiserated.

They untied Daddy from the bed and put him on the floor. Judy put a pillow over Daddy’s face. Janice climbed on top of him and pressed the pillow into his face to stop his breathing. Her three hundred and ninety-seven pounds on his torso crushed all his internal organs before he could even struggle for breath.

And that is how my daddy, Joe Cane Dakin, died, on Ash Wednesday of 1958, in New Orleans, Louisiana.

My seventh birthday.

THE kidnapping became public knowledge shortly after the FBI entered the case. Publicity is one thing that the FBI has always done well.

We were all more or less marooned in Penthouse B. Lawyer Weems hovered like an old bluebottle; his faded marble eyes stared at me often enough to give me the shivers. Sometimes a few tiny bubbles of spittle pearled at the left corner of his mouth, like he was hungry for me.

Mamadee had taken Ford’s bed, forcing him to sleep on a cot and endure the indignity of sharing a room with his grandmama. He was as touchy as a trapped wasp, blaming me for Mamadee’s choice of his room over mine.

I would have slept—if I could have slept—under the piano or on the balcony rather than in the same room with Mamadee. The feeling was more than mutual; Mamadee resented sharing the same air with me so much that her skin seemed to acquire a blue cast, as if she were holding her breath.

Most every day, a migraine knocked Mama flat on her back in her darkened bedroom. When she could get to her feet, she subsisted on Kools and bourbon.

Uncle Billy Cane and Aunt Jude, the only ones who could actually go out unmolested by the press, brought us newspapers and magazines and any other necessaries that the hotel could not provide.

Shrove Tuesday night, when I was supposed to be in bed, I listened at an open window to the cacophony in the streets. It was a lovely noise. I remember it still, and with more clarity than I do most of that bizarre passage in my life. Among the threads, I heard at one point someone drunkenly singing “You Are My Sunshine.”

“You Are My Sunshine” is the state song of Louisiana. Daddy told me.

Sunshine.

I saw more rain than sunshine in New Orleans. The newspapers and radio reported that snow had fallen in Alabama the day we left for Louisiana, and I was not there to see it. I told myself a story: Daddy had gone back home to take snapshots of the snow and would soon bring them to us, to prove the miracle to us. For my birthday. Maybe snow tasted like vanilla ice cream.

Uncle Billy and Aunt Jude brought a birthday cake and a Mile-High Pie to the Penthouse for me. The sight of the cake brought me nothing of the excitement and pleasure that I recalled from previous birthdays. I didn’t want cake, let alone Mile-High Pie. I made my wish and blew out the seven yellow candles in one shaky blow, but Daddy did not return.

My uncle and aunt also provided a few presents wrapped in clown paper—a flat book shape that was probably a paper doll, a flat square that was probably one or two 45s, a small box that likely contained a charm bracelet or a bracelet of polished pebbles—but I just looked at them, and then I went to the door to wait for Daddy.

“Ain’t you gone open your gifts?” Uncle Billy Cane asked me.

I shook my head no. “I’m waiting for Daddy.”

Ford sniggered.

Mamadee was disgusted with me. “Roberta Ann, you are indulging that child.”

Mamadee grabbed me by the shoulders to give me one of her patented shakes. I let out a wail that must have been heard back in Alabama. Uncle Billy Cane wrenched me from Mamadee’s claws. Mamadee was diverted to abusing him as an interfering redneck white-trash no-account, which he ignored as if she were a mosquito.

Aunt Jude picked me up bodily to carry me away into my room. Mama followed her, and stood in the door hesitantly.

Aunt Jude felt my forehead as she sat on the bed and I sat in her lap.

“This child is clammy. She is shivering and shaking.” With a glance at Mama, Aunt Jude added, “Roberta, do something useful. Fetch a jigger of bourbon.”

Mama cocked an eyebrow at Aunt Jude’s temerity but followed the instruction anyway.

Aunt Jude poured the jigger of bourbon into me.

“If that makes her sick,” Mama said, “you can clean it up.”

“The child has made herself ill, fretting after her daddy.” Aunt Jude spoke without acrimony, almost as if Mama had not said anything. “You might have a doctor for her. She is not right, Roberta, not right at all.”

Mama must have been worried that her fitness as a mother might be questioned, because she did summon the hotel doctor.

He examined me, had a low-voiced exchange with Mama and Aunt Jude, and gave me something, a sedative of some kind.

I didn’t care that he had questioned Mama and Aunt Jude about my mental status. “Miz Dakin, I do not misunderstand, do I, this child is weak-minded? Highly suggestible? I see more of it with every passing day. Parents are mystified. Fortunately the cause is easily identified. Don’t let her watch the television or listen to the radio, and never permit her to have comic books. Dear lady, you have more burdens than anyone ought to have to bear, but I must be frank with you. A child of her hysteric tendencies will become more difficult as she approaches puberty. You may have to consider special arrangements. If I can be any help.”

I just wanted him to go away and for Daddy to come back.

That doctor did me a kindness, though, as the sedative he gave me, with the bourbon, brought me a long, velvety oblivion.

The shift of the bed under Mama’s weight when she came in to sleep woke me enough so that I could rub her feet, but I did it in a daze. Only after she was unconscious and I was lying next to her did anything like real mental clarity return. All at once I was fully awake, fully aware of Mama, of my every breath, of the reality in which I was cocooned. The scream that had yanked me to consciousness ached inside my skull. A lightbulb blowing out feels like this, I thought, and, of course, the lightbulb hurt when it died. There was no fear in me anymore, only an expanding unfamiliar silence, a sense that there was nothing more.

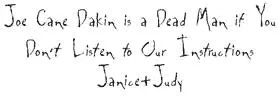

On Thursday, the sixth day, the second ransom note arrived.

Judy DeLucca delivered it herself when she brought up Mama’s coffee and brioche that morning.

“I found this outside the door,” Judy told Mama and handed over a pink envelope.

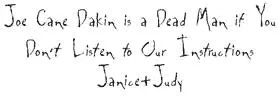

Mamadee and Ford were still slugabed, so we had the new note to ourselves. Mama had a darkness around her eyes like a terrible illness was inside her. The nasty perfume on the note made me sick to my stomach again. Mama grimaced as if the smell hit her that way too. She opened the note.

“Well, what instructions?” Mama said. “What damned instructions?” She looked right at Judy as if she were asking her. “And who is Janice and who the hell is Judy?”

Читать дальше