“The guy in the clown suit,” Chris Unwin said, and shivered. “The guy with the balloons.”

3

The Canal Days Festival, which ran from July 15th to July 21st, had been a rousing success, most Derry residents agreed: a great thing for the city’s morale, image . . . and pocketbook. The week-long festival was pegged to mark the centenary of the opening of the Canal which ran through the middle of downtown. It had been the Canal which had fully opened Derry to the lumber trade in the years 1884 to 1910; it had been the Canal which had birthed Derry’s boom years.

The town was spruced up from east to west and north to south. Potholes which some residents swore hadn’t been patched for ten years or more were neatly filled with hottop and rolled smooth. The town buildings were refurbished on the inside, repainted on the outside. The worst of the graffiti in Bassey Park—much of it coolly logical anti-gay statements such as KILL ALL QUEERS and AIDS FROM GOD YOU HELLBOUND HOMOS!!—was sanded off the benches and wooden walls of the little covered walkway over the Canal known as the Kissing Bridge.

A Canal Days Museum was installed in three empty storefronts downtown, and filled with exhibits by Michael Hanlon, a local librarian and amateur historian. The town’s oldest families loaned freely of their almost priceless treasures, and during the week of the festival nearly forty thousand visitors paid a quarter each to look at eating-house menus from the 1890s, loggers’ bitts, axes, and peaveys from the 1880s, children’s toys from the 1920s, and over two thousand photographs and nine reels of movie film of life as it had been in Derry over the last hundred years.

The museum was sponsored by the Derry Ladies’ Society, which vetoed some of Hanlon’s proposed exhibits (such as the notorious tramp-chair from the 1930s) and photographs (such as those of the Bradley Gang after the notorious shoot-out). But all agreed it was a great success, and no one really wanted to see those gory old things anyway. It was so much better to accentuate the positive and eliminate the negative, as the old song said.

There was a huge striped refreshment tent in Derry Park, and band concerts there every night. In Bassey Park there was a carnival with rides by Smokey’s Greater Shows and games run by local townfolk. A special tram-car circled the historic sections of the town every hour on the hour and ended up at this gaudy and amiable money-machine.

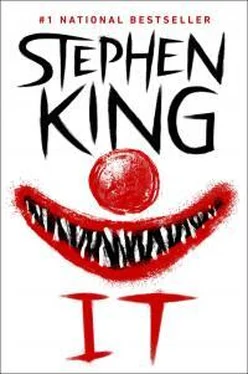

It was here that Adrian Mellon won the hat which would get him killed, the paper top-hat with the flower and the band which said I DERRY!

4

“I’m tired,” John “Webby” Garton said. Like his two friends, he was dressed in unconscious imitation of Bruce Springsteen, although if asked he would probably call Springsteen a wimp or a fagola and would instead profess admiration for such “bitchin” heavy-metal groups as Def Leppard, Twisted Sister, or Judas Priest. The sleeves of his plain blue tee-shirt were torn off, showing his heavily muscled arms. His thick brown hair fell over one eye—this touch was more John Cougar Mellencamp than Springsteen. There were blue tattoos on his arms—arcane symbols which looked as if they had been drawn by a child. “I don’t want to talk no more.”

“Just tell us about Tuesday afternoon at the fair,” Paul Hughes said. Hughes was tired and shocked and dismayed by this whole sordid business. He thought again and again that it was as if Derry Canal Days ended with one final event which everyone had somehow known about but which no one had quite dared to put down on the Daily Program of Events. If they had, it would have looked like this:

Saturday, 9:00 P.M. : Final band concert featuring the Derry High School Band and the Barber Shop Mello-Men.

Saturday, 10:00 P.M. : Giant fireworks show.

Saturday, 10:35 P.M. : Ritual sacrifice of Adrian Mellon officially ends Canal Days.

“Fuck the fair,” Webby replied.

“Just what you said to Mellon and what he said to you.”

“Oh Christ.” Webby rolled his eyes.

“Come on, Webby,” Hughes’s partner said.

Webby Garton rolled his eyes and began again.

5

Garton saw the two of them, Mellon and Hagarty, mincing along with their arms about each other’s waists and giggling like a couple of girls. At first he actually thought they were a couple of girls. Then he recognized Mellon, who had been pointed out to him before. As he looked, he saw Mellon turn to Hagarty . . . and they kissed briefly.

“Oh, man, I’m gonna barf!” Webby cried, disgusted.

Chris Unwin and Steve Dubay were with him. When Webby pointed out Mellon, Steve Dubay said he thought the other fag was named Don somebody, and that he’d picked up a kid from Derry High hitching and then tried to put a few moves on him.

Mellon and Hagarty began to move toward the three boys again, walking away from the Pitch Til U Win and toward the carny’s exit. Webby Garton would later tell Officers Hughes and Conley that his “civic pride” had been wounded by seeing a fucking faggot wearing a hat which said I DERRY. It was a silly thing, that hat—a paper imitation of a top hat with a great big flower sticking up from the top and nodding about in every direction. The silliness of the hat apparently wounded Webby’s civic pride even more.

As Mellon and Hagarty passed, each with his arm linked about the other’s waist, Webby Garton yelled out: “I ought to make you eat that hat, you fucking ass-bandit!”

Mellon turned toward Garton, fluttered his eyes flirtatiously, and said: “If you want something to eat, hon, I can find something much tastier than my hat.”

At this point Webby Garton decided he was going to rearrange the faggot’s face. In the geography of Mellon’s face, mountains would rise and continents would drift. Nobody suggested he sucked the root. Nobody.

He started toward Mellon. Mellon’s friend Hagarty, alarmed, attempted to pull Mellon away, but Mellon stood his ground, smiling. Garton would later tell Officers Hughes and Conley that he was pretty sure Mellon was high on something. So he was, Hagarty would agree when this idea was passed on to him by Officers Gardener and Reeves. He was high on two fried doughboys smeared with honey, on the carnival, on the whole day. He had been consequently unable to recognize the real menace which Webby Garton represented.

“But that was Adrian,” Don said, using a tissue to wipe his eyes and smearing the spangled eyeshadow he was wearing. “He didn’t have much in the way of protective coloration. He was one of those fools who think things really are going to turn out all right.”

He might have been badly hurt there and then if Garton hadn’t felt something tap his elbow. It was a nightstick. He turned his head to see Officer Frank Machen, another member of Derry’s Finest.

“Never mind, little buddy,” Machen told Garton. “Mind your business and leave those little gay boyos alone. Have some fun.”

“Did you hear what he called me?” Garton asked hotly. He was now joined by Unwin and Dubay—the two of them, smelling trouble, tried to urge Garton on up the midway, but Garton shrugged them away, would have turned on them with his fists if they had persisted. His masculinity had borne an insult which he felt must be avenged. Nobody suggested he sucked the root. Nobody.

“I don’t believe he called you anything,” Machen replied. “And you spoke to him first, I believe. Now move on, sonny. I don’t want to have to tell you again.”

“He called me a queer!”

“Are you worried you might be, then?” Machen asked, seeming to be honestly interested, and Garton flushed a deep ugly red.

During this exchange, Hagarty was trying with increasing desperation to pull Adrian Mellon away from the scene. Now, at last, Mellon was going.

Читать дальше