“There are only so many tomorrows.”

—MICHAEL LANDON

Marsden’s house came into view. It was like one of those Hollywood Hills mansions you see in the movies: big and jutting out over the drop. The side facing us was all glass .

“The house that heroin built.” Liz sounded vicious .

There was one more curve before we came to the paved yard in front of the house. Liz drove around it and I saw a man in front of the double garage where Marsden’s fancy cars were. I opened my mouth to say it must be Teddy, the gatekeeper, but then I saw his mouth was gone .

And given the red hole where his mouth had been, he hadn’t died a natural death .

Like I said, this is a horror story…

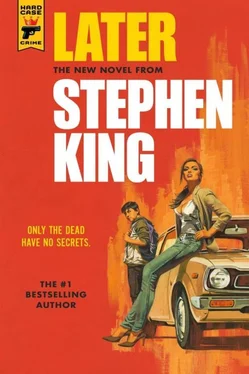

I don’t like to start with an apology—there’s probably even a rule against it, like never ending a sentence with a preposition —but after reading over the thirty pages I’ve written so far, I feel like I have to. It’s about a certain word I keep using. I learned a lot of four-letter words from my mother and used them from an early age (as you will find out), but this is one with five letters. The word is later , as in “Later on” and “Later I found out” and “It was only later that I realized.” I know it’s repetitive, but I had no choice, because my story starts when I still believed in Santa Claus and the Tooth Fairy (although even at six I had my doubts). I’m twenty-two now, which makes this later, right? I suppose when I’m in my forties—always assuming I make it that far—I’ll look back on what I thought I understood at twenty-two and realize there was a lot I didn’t get at all. There’s always a later, I know that now. At least until we die. Then I guess it’s all before that .

My name is Jamie Conklin, and once upon a time I drew a Thanksgiving turkey that I thought was the absolute cat’s ass. Later—and not much later—I found out it was more like the stuff that comes out of the cat’s ass. Sometimes the truth really sucks.

I think this is a horror story. Check it out.

I was coming home from school with my mother. She was holding my hand. In the other hand I clutched my turkey, the ones we made in first grade the week before Thanksgiving. I was so proud of mine I was practically shitting nickels. What you did, see, was put your hand on a piece of construction paper and then trace around it with a crayon. That made the tail and body. When it came to the head, you were on your own.

I showed mine to Mom and she’s all yeah yeah yeah, right right right, totally great, but I don’t think she ever really saw it. She was probably thinking about one of the books she was trying to sell. “Flogging the product,” she called it. Mom was a literary agent, see. It used to be her brother, my Uncle Harry, but Mom took over his business a year before the time I’m telling you about. It’s a long story and kind of a bummer.

I said, “I used Forest Green because it’s my favorite color. You knew that, right?” We were almost to our building by then. It was only three blocks from my school.

She’s all yeah yeah yeah. Also, “You play or watch Barney and The Magic Schoolbus when we get home, kiddo, I’ve got like a zillion calls to make.”

So I go yeah yeah yeah, which earned me a poke and a grin. I loved it when I could make my mother grin because even at six I knew that she took the world very serious. Later on I found out part of the reason was me. She thought she might be raising a crazy kid. The day I’m telling you about was the one when she decided for sure I wasn’t crazy after all. Which must have been sort of a relief and sort of not.

“You don’t talk to anybody about this,” she said to me later that day. “Except to me. And maybe not even me, kiddo. Okay?”

I said okay. When you’re little and it’s your mom, you say okay to everything. Unless she says it’s bedtime, of course. Or to finish your broccoli.

We got to our building and the elevator was still broken. You could say things might have been different if it had been working, but I don’t think so. I think that people who say life is all about the choices we make and the roads we go down are full of shit. Because check it, stairs or elevator, we still would have come out on the third floor. When the fickle finger of fate points at you, all roads lead to the same place, that’s what I think. I may change my mind when I’m older, but I really don’t think so.

“Fuck this elevator,” Mom said. Then, “You didn’t hear that, kiddo.”

“Hear what?” I said, which got me another grin. Last grin for her that afternoon, I can tell you. I asked her if she wanted me to carry her bag, which had a manuscript in it like always, that day a big one, looked like a five-hundred-pager (Mom always sat on a bench reading while she waited for me to get out of school, if the weather was nice). She said, “Sweet offer, but what do I always tell you?”

“You have to tote your own burden in life,” I said.

“Correctamundo.”

“Is it Regis Thomas?” I asked.

“Yes indeed. Good old Regis, who pays our rent.”

“Is it about Roanoke?”

“Do you even have to ask, Jamie?” Which made me snicker. Everything good old Regis wrote was about Roanoke. That was the burden he toted in life.

We went up the stairs to the third floor, where there were two other apartments plus ours at the end of the hall. Ours was the fanciest one. Mr. and Mrs. Burkett were standing outside 3A, and I knew right away something was wrong because Mr. Burkett was smoking a cigarette, which I hadn’t seen him do before and was illegal in our building anyway. His eyes were bloodshot and his hair was all crazied up in gray spikes. I always called him mister, but he was actually Professor Burkett, and taught something smart at NYU. English and European Literature, I later found out. Mrs. Burkett was dressed in a nightgown and her feet were bare. That nightgown was pretty thin. I could see most of her stuff right through it.

My mother said, “Marty, what’s wrong?”

Before he could say anything back, I showed him my turkey. Because he looked sad and I wanted to cheer him up, but also because I was so proud of it. “Look, Mr. Burkett! I made a turkey! Look, Mrs. Burkett!” I held it up for her in front of my face because I didn’t want her to think I was looking at her stuff.

Mr. Burkett paid no attention. I don’t think he even heard me. “Tia, I have some awful news. Mona died this morning.”

My mother dropped her bag with the manuscript inside it between her feet and put her hand over her mouth. “Oh, no! Tell me that’s not true!”

He began to cry. “She got up in the night and said she wanted a drink of water. I went back to sleep and she was on the couch this morning with a comforter pulled up to her chin and so I tiptoed to the kitchen and put on the coffee because I thought the pleasant smell would w-w-wake… would wake…”

He really broke down then. Mom took him in her arms the way she did me when I hurt myself, even though Mr. Burkett was about a hundred (seventy-four, I found out later).

That was when Mrs. Burkett spoke to me. She was hard to hear, but not as hard as some of them because she was still pretty fresh. She said, “Turkeys aren’t green, James.”

“Well mine is,” I said.

My mother was still holding Mr. Burkett and kind of rocking him. They didn’t hear her because they couldn’t, and they didn’t hear me because they were doing adult things: comforting for Mom, blubbering for Mr. Burkett.

Читать дальше