“Um … more like concerned mother, I guess?”

Lace advanced on me, stuck one stiff forefinger into the center of my chest, her smell overwhelming me as she shouted, “Well, let’s get something straight, Cal. I am not… your… baby !”

She spun on her heel and stomped to the apartment door, unlocking it and yanking it open. She turned back, pulling something from her pocket. For a second, I thought she was going to throw it at me in a wild rage.

But her voice was even. “I found this in Max’s kitchen trash. Guess Morgan never bothered to get her mail forwarded.”

She flicked it at me after all, the envelope spinning like a ninja’s star.

I plucked it from the air and turned it over. It was addressed to Morgan. Just a random piece of junk mail, but now I had a last name.

“Morgan Ryder. Hey, thanks for—”

The door slammed shut. Lace was gone.

I stared after her for a while, the echo of her exit ringing in my exquisite hearing. I could still smell the jasmine fragrance in the air, the scent of her anger, and traces of her skin oil and sweat on my fingers. Her departure had been so sudden, it took a moment to accept it.

It was better this way, of course. I’d been lucky so far. Those moments on the balcony had been too intense and unexpected. It was one thing sitting across a table from Lace in a crowded restaurant, but I couldn’t be alone with her, not in small spaces. I liked her too much, and after six months of celibacy, the parasite was stronger than I was.

And once she thought about my cover story a little more, she’d probably figure I was some kind of thief or con man or just plain freaky. So maybe she’d steer clear of me from now on.

I let out a long, sad sigh, then continued sweeping for bodily fluids.

A long time ago human beings were hairy all over, like monkeys. Nowadays, however, we wear clothes to keep us warm.

How did this switch happen? Did we lose the fur and then decide to invent clothes? Or did we invent clothing and then lose the body hair that we no longer needed?

The answer isn’t in any history books, because writing hadn’t been invented yet when it happened. But fortunately, our little friends the parasites remember. They carry the answer in their genes.

Lice are bloodsuckers that live on people’s heads. So small that you can barely see them, they hide in your hair. Once they’ve infested one person, they spread like a rumor, carrying trench fever, typhus, and relapsing fever. Like most bloodsuckers, lice are unpopular. That’s why the word lousy is generally not a compliment.

You can’t fault lousy loyalty, though. Human lice have been with us for five million years, since our ancestors split off from chimpanzees. That’s a long run together. (The tapeworm, for comparison, has only been inside us for about eight thousand years, a total parasite-come-lately.) At the same time we were evolving away from monkeys, our parasites were evolving from monkey parasites—coming along for the ride.

But I bet that our lice wish they hadn’t bothered. You see, while the chimps stayed hairy, we humans lost most of our body hair. So now human lice have only our hairy heads to hide in. On top of that, they’re always getting poisoned by shampoo and conditioner, which is why lice have become rare in wealthy countries.

But lice aren’t utterly doomed. When people started wearing clothing, some lice evolved to take advantage of the new situation. They developed claws that are adapted for clinging to fabric instead of hair. So these days, there are two species of human lice: hair-loving head lice and clothes-loving body lice.

Evolution marches on. Maybe one day we’ll have space suit lice.

So what does this have to do with the invention of clothing?

Not long ago, scientists compared the DNA of three kinds of lice: head lice, body lice, and the old original chimp lice. As time passes, DNA changes at a fixed rate, so scientists can tell roughly how long ago any two species split up from each other. Comparing lice DNA soon settled the question of what came first—the clothes or the nakedness.

Here’s how it happened:

Human lice and monkey lice split off from each other about 1.8 million years ago. That’s when ancient humans lost their body hair and the lice we inherited from the chimps had to adapt, evolving to stick to our heads.

But head lice and body lice didn’t split until seventy-two thousand years ago, an eternity later (especially in lice years). That’s when human beings invented clothes, and body lice evolved to reclaim some of their lost real estate. They got brand-new claws and spread down into our brand-new clothing.

So that’s the answer: Clothes got invented after we lost our body hair. And not right away; our primate ancestors ran around naked and hairless for well over a million years.

That part of human evolution is written in lousy history, in the genes of the things that suck our blood.

Just as I finished Freddie’s apartment (finding no glimmer of bodily fluids), my phone buzzed. One of the Shrink’s minders was on the other end, saying that she wanted to see me again. My stack of forms had returned from Records, chock-full of enough intrigue to bounce all the way up to the Shrink. That was always a sign of progress.

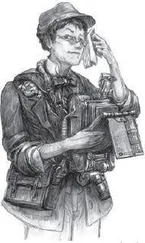

Still, I sometimes wished she would just talk to me on the phone and not insist on quite so much face time. But she’s so old-school that telephones just aren’t her thing. In fact, electricity isn’t her thing.

I wonder if I’ll ever get that ancient.

I took the subway down to Wall Street, then walked across. The Shrink’s house is on a crooked alley paved with cobblestones, barely one car wide. It’s one of those New Amsterdam originals that the Dutch laid down four centuries ago, running on the diagonal, flouting the grid in the same grumpy way that the Shrink ignores telephones. Those early streets possess their own logic; they were built atop the age-old hunting trails of the Manhattan Indians. Of course, the Indians were only following even more ancient paths created by deer.

And who were the deer copying ? I wondered. Maybe my route had first been cut through the primeval forest by a line of hungry ants.

One thing about carrying the parasite—it makes you feel connected to the past. As a peep, I’m a blood brother to every other parasite-positive throughout the ages. There’s an unbroken chain of biting, scratching, unprotected sex, rat reservoirs, and various other forms of fluid-sharing between me and that original slavering maniac, the poor human who was first infected with the disease.

So where did he or she get it from ? you may ask. From elsewhere in the animal kingdom. Most parasites leap to humanity from other species. Of course, it was a long time ago, so the original parasite-positive wasn’t exactly what we’d call human. More likely the first peep was some early Cro-Magnon who was bitten by a dire wolf or giant sloth or saber-toothed weasel.

I kicked a bag of garbage next to the Shrink’s stoop and heard the skittering of tiny claws inside it. A few little faces peeked out to glare at me; then one rat jumped free and scampered a few yards down the alley, disappearing down a hole among the cobblestones.

There are more of those holes than you’d think.

When I first came to the city, I saw only street level, or sometimes caught glimpses of the netherworld through exhaust grates or down empty subway tracks. But in the Night Watch we see the city in layers. We feel the sewers and the hollow sidewalks carrying electrical cables and steam pipes, and below that the older spaces: the basements of fallen buildings, the giant buried caskets of abandoned breweries, the ancient septic tanks, the forgotten graveyards. And, struggling to get free underneath, the old streambeds and natural springs—all those pockets where rats, and much bigger things, can thrive.

Читать дальше