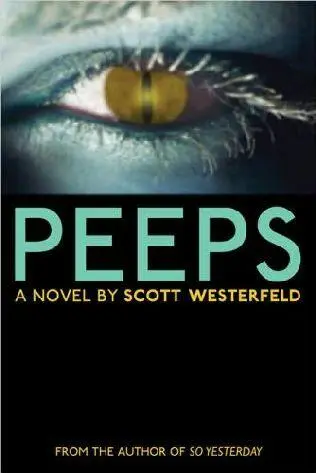

Peeps

(Parasite Positive)

(The first book in the Peeps series)

Scott Westerfeld

After a year of hunting, I finally caught up with Sarah.

It turned out she’d been hiding in New Jersey, which broke my heart. I mean, Hoboken ? Sarah was always head-over-heels in love with Manhattan. For her, New York was like another Elvis, the King remade of bricks, steel, and granite. The rest of the world was a vast extension of her parents’ basement, the last place she wanted to wind up.

No wonder she’d had to leave when the disease took hold of her mind. Peeps always run from the things they used to love.

Still, I shook my head when I found out where she was. The old Sarah wouldn’t have been caught dead in Hoboken. And yet here I was, finishing my tenth cup of coffee in the crumbling parking lot of the old ferry terminal, armed only with my wits and a backpack full of Elvis memorabilia. In the black mirror of the coffee’s surface, the gray sky trembled with the beating of my heart.

* * *

It was late afternoon. I’d spent the day in a nearby diner, working my way through the menu and waiting for the clouds to clear, praying that the bored and very cute waitress wouldn’t start talking to me. If that happened, I’d have to leave and wander around the docks all day.

I was nervous—the usual tension of meeting an ex, with the added bonus of facing a maniacal cannibal—and the hours stretched out torturously. But finally a few shafts of sun had broken through, bright enough to trap Sarah inside the terminal. Peeps can’t stand sunlight.

It had been raining a lot that week, and green weeds pushed up through the asphalt, cracking the old parking lot like so much dried mud. Feral cats watched me from every hiding place, no doubt drawn here by the spiking rat population. Predators and prey and ruin—it’s amazing how quickly nature consumes human places after we turn our backs on them. Life is a hungry thing.

According to the Night Watch’s crime blotters, this spot didn’t show any of the usual signs of a predator. No transit workers gone missing, no homeless people turning psychotically violent. But every time New Jersey Pest Control did another round of poisoning, the hordes of rats just reappeared, despite the fact that there wasn’t much garbage to eat in this deserted part of town. The only explanation was a resident peep. When the Night Watch had tested one of the rats, it had turned out to be of my bloodline, once removed.

That could only mean Sarah. Except for her and Morgan, every other girl I’d ever kissed was already locked up tight. (And Morgan, I was certain, was not hiding out in an old ferry terminal in Hoboken.)

Big yellow stickers plastered the terminal’s padlocked doors, warning of rat poison, but it looked like the guys at pest control were starting to get spooked. They’d dropped off their little packets of death, slapped up a few warning stickers, and then gotten the heck out of there.

Good for them. They don’t get paid enough to deal with peeps.

Of course, neither do I, despite the excellent health benefits. But I had a certain responsibility here. Sarah wasn’t just the first of my bloodline—she was my first real girlfriend.

My only real girlfriend, if you must know.

We met the opening day of classes—freshman year, Philosophy 101—and soon found ourselves in a big argument about free will and predetermination. The discussion spilled out of class, into a café, and all the way back to her room that night. Sarah was very into free will. I was very into Sarah.

The argument went on that whole semester. As a bio major, I figured “free will” meant chemicals in your brain telling you what to do, the molecules bouncing around in a way that felt like choosing but was actually the dance of little gears—neurons and hormones bubbling up into decisions like clockwork. You don’t use your body; it uses you.

Guess I won that one.

There were signs of Sarah everywhere. All the windows at eye level were smashed, every expanse of reflective metal smeared with dirt or something worse.

And of course there were rats. Lots of them. I could hear that even from outside.

I squeezed between the loosely padlocked doors, then stood waiting for my vision to adjust to the darkness. The sound of little feet skittered along the gloomy edges of the vast interior space. My entrance had the effect of a stone landing in a still pond: The rippling rats took a while to settle.

I listened for my ex-girlfriend but heard only wind whistling over broken glass and the myriad nostrils snuffling around me.

They stayed in the shadows, smelling the familiarity of me, wondering if I was part of the family. Rats have evolved into an arrangement with the disease, you see. They don’t suffer from infection.

Human beings aren’t so lucky. Even people like me—who don’t turn into ravening monsters, who don’t have to run from everything they love—we suffer too. Exquisitely.

I dropped my backpack to the floor and pulled out a poster, unrolling it and taping it to the inside of the door.

I stepped back, and the King smiled down at me through the darkness, resplendent against black velvet. No way could Sarah get past those piercing green eyes and that radiant smile.

Feeling safer under his gaze, I moved farther into the darkness. Long benches lined the floor like church pews, and the faded smell of long-gone human crowds rose up. Passengers had once sat here to await the next ferry to Manhattan. There were a few beds of newspaper where homeless people had slept, but my nose informed me that they’d lain empty for weeks.

Since the predator had arrived.

The hordes of tiny footsteps followed me warily, still unsure of what I was.

I taped a black-velvet Elvis poster onto each exit from the terminal, the bright colors clashing with the dingy yellow of the rat-poison warnings. Then I postered the broken windows, plastering every means of escape with the King’s face.

Against one wall, I found pieces of a shredded shirt. Stained with fresh-smelling blood, it had been flung aside like a discarded candy wrapper. I had to remind myself that this creature wasn’t really Sarah, full of free will and tidbits of Elvis trivia. This was a cold-blooded killer.

Before I zipped the backpack closed, I pulled out an eight-inch ‘68 Comeback Special action figure and put it in my pocket. I hoped my familiar face would protect me, but it never hurts to have a trusty anathema close at hand.

I heard something from above, where the old ferry administration offices jutted out from the back wall, overlooking the waiting room. Peeps prefer to nest in small, high places.

There was only one set of stairs, the steps sagging like a flat tire in the middle. As my weight pressed into the first one, it creaked unhappily.

The noise didn’t matter—Sarah had to know already someone was here—but I went carefully, letting the staircase’s sway settle between every step. The guys in Records had warned me that this place had been condemned for a decade.

I took advantage of the slow ascent to leave a few items from my backpack on the stairs. A sequined cape, a miniature blue Christmas tree, an album of Elvis Sings Gospel .

From the top of the stairs, a row of skulls looked down at me.

I’d seen lairs marked this way before, part territorialism—a warning to other predators to stay away—and partly the sort of thing that peeps just … liked. Not free will but those chemicals in the brain again, determining aesthetic responses, as predictable as a middle-aged guy buying a red sports car.

Читать дальше