I read the papers, I look around, and I have a sinking feeling that these black holes are growing larger, more common, feeding on their own vile appetite. They are not restricted to strange cities in distant countries.

Without telling Amrita any of this, I asked her recently about astronomical black holes. She gave a long explanation, much of it based on the work of a man named Stephen Hawking, much of it technical, most of it indecipherable to me. But a couple of things she mentioned interested me. First, she said that it did look as if light and other captured energies might be able to escape astronomical black holes after all. I forget the details of her explanation, but the impression I got was that although it was impossible to climb out of a black hole, energy might "tunnel out" into another place and time. Second, she said that even if all the matter and energy in the universe were gobbled up by black holes, it would only ensure that the mass came together into another Big Bang that would start what she called a Fresh New Universe with new laws, new forms, and blazing new galaxies of light.

Maybe. I sit on a mountaintop and weave weak metaphors, all the while remembering a pale hint of cheek in a dirty shawl. Sometimes I touch the palm of my hand in an attempt to recall the sensation the last time I cupped Victoria's head in my hand. Take care of your mom until I get back, okay, Little One?

And the wind rises outside and the stars shake in the chill of night.

Amrita is pregnant. She hasn't told me yet, but I know that she confirmed it with her doctor two days ago. I think she's worried about what my reaction will be. She needn't be.

A month ago, just before school started again in September, Amrita and I took the Bronco up to the end of an old mining road and then backpacked about three miles along the ridgeline. There was no sound except for the breeze through the pines below us. The valleys there were either never inhabited or abandoned when the old mines played out. We explored a few of the old diggings and then crossed another ridge to where we could see snow-topped peaks extending away in all directions, to and beyond the curve of the planet. We paused to watch a hawk circle silently on high thermals half a mile above us.

That night we camped near a high lake, a small, perfect circle of painfully cold snowmelt. The half-moon rose about midnight and cast a pale brilliance on the surrounding peaks. Patches of snow caught the moonlight on the rocky slope near us.

Amrita and I made love that night. It was not the first time since Calcutta, but it was the first time we were able to forget everything except each another. Afterward, Amrita fell asleep with her head on my chest while I lay there and watched the Perseid meteors cut their way across the August night sky. I counted twenty-eight before I fell asleep.

Amrita is thirty-eight, almost thirty-nine. I'm sure that her doctor will recommend amniocentesis. I'm going to urge her not to go through that. Amniocentesis is helpful primarily if the parents are willing to abort the fetus if there are genetic problems. I don't think we are. I also feel — feel very strongly — that there will be no problems.

It might be best if we were to have a boy this time, but it will be fine either way. There will be painful recollections with a baby in the house, but it will be less painful than the hurt we've shared so long now.

I still believe that some places are too wicked to be suffered. Occasionally, I dream of nuclear mushroom clouds rising above a city and human figures dancing against the flaming pyre that once was Calcutta.

Somewhere there are dark choruses ready to proclaim the Age of Kali. I am sure of this. As sure as I am that there will always be servants to do Her bidding.

All violence is power, Mr. Luczak.

Our child will be born in the spring. I want him or her to know all of the pleasures of hillsides under clear skies, of hot chocolate on a winter's morning, and of laughter on a grassy Saturday afternoon in summer. I want our child to hear the friendly voices of good books and the even-friendlier silences in the company of good people.

I have not written any poetry in years, but recently I bought a large, well-bound book of blank pages and I've written in it every day. It is not poetry. It is not for publication. It is a story — a series of stories, actually — about the adventures of a group of unlikely friends. There is a talking cat, a fearless and precocious mouse, a gallant but lonely centaur, and a vainglorious eagle who is afraid to fly. It is a story about courage and friendship and small quests to interesting places. It is a bedtime storybook.

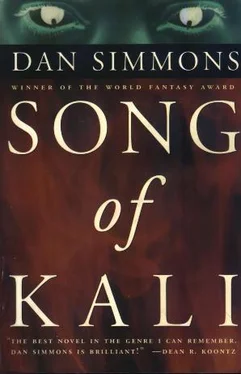

The Song of Kali is with us. It has been with us for a very long time. Its chorus grows and grows and grows.

But there are other voices to be heard. There are other songs to be sung.