Amrita and I never talked about Calcutta. We did not mention Victoria's name. Amrita was retreating into a world of number theory and Boolean Algebra. It seemed to be a comfortable world for her: a world in which rules were abided by and truth tables could be logically determined. I was left outside with nothing but my unwieldy tools of language and the unfixable, nonsensical machine of reality.

I was at the college for four months and might not have returned to Exeter if a friend had not called to tell me that Amrita had been hospitalized. Doctors diagnosed her problem as acute pneumonia complicated by exhaustion. She was hospitalized for eight days and too weak to get out of bed at home for a week after that. I stayed home during that time, and in the small acts of nursing I was beginning to feel echoes of our earlier tenderness; but then she announced that she felt better, she returned to her computer work in mid-June, and I went back to my apartment. I felt irresolute and lost, as if some huge, dark hole was opening wider in me, sucking me down.

I bought the Luger that June.

Roy Bennet, a taciturn little biology professor I'd met at the college, had invited me to his gun club in April. For years I had supported gun-control laws and hated the idea of handguns, but by the end of that school year I was spending most Saturdays on the firing range with Bennet. Even the children there seemed proficient at the two-handed, wide-legged firing stance that I knew only from the movies. When someone had to retrieve a target, everyone politely broke their weapons open and stepped back from the firing line with a smile. Many of the targets were in the shape of human bodies.

When I suggested that I would like to buy my own gun, Roy smiled with the quiet joy of a successful missionary and suggested that a .22-caliber target pistol would be good to start with. I nodded agreement, and the next day spent a small fortune for a vintage 7.65mm Luger. The woman who sold it said that the automatic had been her late husband's pride and joy. She included a handsome carrying case in the price.

I never mastered the preferred two-handed stance, but became reasonably proficient at putting holes in the target at twenty yards. I had no idea what the others were thinking or feeling as they plinked away on those long-shadowed evenings, but each time I raised that oiled and balanced instrument I felt the power of its pent-up energy course through me like a shot of strong whiskey. The slow, careful squeezing, the deafening report, and the blow of the recoil along my stiffened arm created something akin to ecstasy in me.

I brought the Luger back to Exeter with me one weekend after Amrita's recovery. She came downstairs late one night and found me turning the freshly oiled and loaded weapon over and over in my hands. She said nothing, but looked at me for a long moment before going back upstairs. Neither of us mentioned it in the morning.

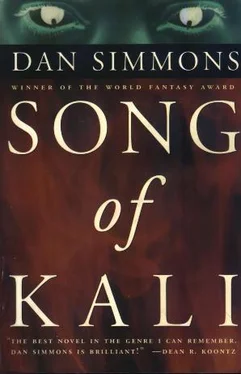

"There's a new book out in India. Quite the rage. An epic poem, I believe. All about Kali, one of their tutelary goddesses," said the book salesman.

I had come down to New York for a party at Doubleday, attracted more by the offer of free drinks than by anything else. I was on the balcony and debating whether to get my fourth Scotch when I heard the salesman talking to two distributors. I went over and took him by the arm, led him to a far corner of the balcony. The man had just returned from a trade fair in New Delhi. He did not know who I was. I explained that I was a poet interested in contemporary Indian writing.

"Yes, well, I'm afraid I can't tell you much about this book," he said. "I mentioned it because it seemed such a damned unlikely thing to be selling so well over there. Just a long poem, really. I guess it's taken the Indian intellectuals by storm. We wouldn't be interested, of course. Poetry never sells here, much less if it's —"

"What's the title?" I asked.

"It's funny, but I did remember that," he said. " Kalisambv-ha or Kalisavba or something like that. I remembered it because I used to work with a girl named Kelly Summers and I noticed the —"

"Who's the author?"

"Author? I'm sorry, I don't recall that. I only remember the book because the publisher had this huge display but no real graphics, you know? Just this big pile of books there. I kept seeing the blue cover in all the bookstores in the Delhi hotels. Have you ever been to India?"

"Das?"

"What?"

"Was the author's name Das?" I said.

"No, it wasn't Das," he said. "At least I don't think so. Something Indian and hard to pronounce, I think."

"Was his first name Sanjay?" I asked.

"Sorry, I have no idea," said the salesman. He was becoming irritated. "Look, does it make that much difference?"

"No," I said, "it doesn't make any difference." I left him and went to lean on the balcony railing. I was still there two hours later when the moon rose over the serrated teeth of the city.

I received the photograph in mid-July.

Even before I saw the postmark I knew the letter was from India. The smell of the country rose from the flimsy envelope. It was postmarked Calcutta. I stood at the end of our drive under the leaves of the big birch tree and opened the envelope.

I saw the note on the back of the photograph first. It said Das is alive , nothing more. The photo was in black and white, grainy; the people in the foreground were almost washed out by a poorly used flash while the people in the near background were mere silhouettes. Das, however, was immediately recognizable. His face was scabbed and the nose was distorted, but the leprosy was not nearly so obvious as when I had met him. He was wearing a white shirt, and his hand was extended as if he were making a point to students.

The eight men in the photo were all seated on cushions around a low table. The flash showed paint peeling from a wall behind Das and a few dirty cups on the table. Two other men's faces were clearly illuminated, but I did not know them. My eyes went to a silhouette of a man seated on Das's right. It was too dark to make out facial features, but there was enough profile for me to see the predatory beak of a nose and the hair standing out like a black nimbus.

There was nothing in the envelope except the photograph.

Das is alive . What was I supposed to make of that? That M. Das had been resurrected yet another time by his bitch goddess? I looked at the photo again and stood tapping it against my fingers. There was no way of telling when the picture had been taken. Was the figure in the shadows Krishna? There was something about the hunched-forward aggressiveness of the head and body that made me want to say it was.

Das is alive.

I turned away from the driveway and walked into the woods. Underbrush grabbed at my ankles. There was a tilting, spinning emptiness inside me that threatened to open into a black chasm. I knew that once the darkness opened, there would be no hope of my escaping it.

A quarter of a mile from the house, near where the stream widened into a marshy area, I knelt and tore the photograph into tiny pieces. Then I rolled a large rock over and sprinkled the pieces onto the matted, faded ground there before rolling the rock back in place.

While walking home I retained the image of moist white things burrowing frantically to avoid the light.

Amrita came into the room that night while I was packing. "We need to talk," she said.

"When I get back," I said.

"Where are you going, Bobby?"

"New York," I said. "Just for a couple of days." I put another shirt over the place where I had packed away the Luger and 64 cartridges.

"It's important that we talk," said Amrita. Her hand touched my arm.

I pulled away and zipped closed my black suitcase. "When I get back," I said.

Читать дальше