“Thanks,” I say, and get into the driver’s seat. “I’ll be back as soon as I can.” Anna snakes her pale leg over the front seat and drops herself down shotgun.

“I’m going with you.”

I’m not going to argue. I could use the company. I start the car back up and drive. Anna does nothing but watch the trees and buildings go by. I suppose the change of scenery must be interesting to her, but I wish she would say something.

“Did Carmel hurt you, back there?” I ask just for noise.

She smiles. “Don’t be silly.”

“Have you been okay, at the house?”

There’s a stillness on her face that has to be deliberate. She’s always so still, but I get the feeling that her mind is sort of like a shark, twisting and swimming, and all I’ve ever seen is a glimpse of dorsal fin.

“They keep on showing me,” she says carefully. “But they’re still weak. Other than that, I’ve just been waiting.”

“Waiting for what?” I ask. Don’t judge me. Sometimes playing dumb is the only move you’ve got. Unfortunately, Anna doesn’t chase the ball. So we sit, and I drive, and on the tip of my tongue are the words to tell her that I don’t have to do it. I have a very strange life and she’d fit into it. Instead I say, “You didn’t have a choice.”

“It doesn’t matter.”

“How can it not?”

“I don’t know, but it doesn’t,” she replies. I catch her smile in the corner of my eye. “I wish it didn’t have to hurt you,” she says.

“Do you?”

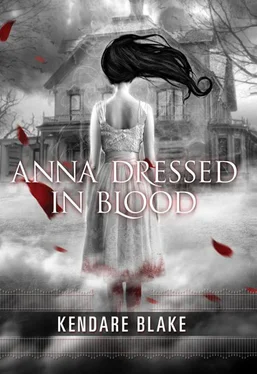

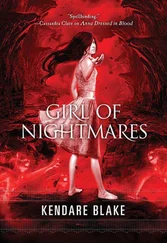

“Of course. Believe me, Cassio. I never wanted to be this tragic.”

My house is cresting over the hill. To my relief, my mom’s car is parked out front. I could continue this conversation. I could get in a jab, and we could argue. But I don’t want to. I want to put this down and focus on the problem at hand. Maybe I’ll never have to deal with this. Maybe something will change.

I pull into my driveway and we get out, but as we walk up the porch steps, Anna starts to sniff. She’s squinting like her head hurts.

“Oh,” I say. “Right. I’m sorry. I forgot about the spell.” I shrug weakly. “You know, a few herbs and chants and then nothing dead comes through the door. It’s safer.”

Anna crosses her arms and leans against the railing. “I understand,” she says. “Go and get your mother.”

Inside, I hear my mom humming some little tune I don’t know, probably something she made up. I see her pass by the archway in the kitchen, her socks sliding across the hardwood and the tie from her sweater dragging behind on the ground. I walk up and grab it.

“Hey!” she says with an irritated look. “Shouldn’t you be in school?”

“You’re lucky it was me and not Tybalt,” I say. “Or this sweater thing would be in shreds.”

She sort of huffs at me and ties it around her waist where it belongs. The kitchen smells like flowers and persimmon. It’s a warm, wintry smell. She’s making a new batch of her Blessed Be Potpourri, just like she does every year. It’s a big seller on the website. But I’m procrastinating.

“So?” she asks. “Aren’t you going to tell me why you’re not in school?”

I take a deep breath. “Something’s happened.”

“What?” Her tone is almost tired, like she half-expects just this sort of bad news. She’s probably always expecting bad news of one kind or another, knowing what I do. “Well?”

I don’t know how to tell her this. She might overreact. But is there such a thing in this situation? Now I’m staring into a very worried and agitated mom-face.

“Theseus Cassio Lowood, you’d better spit it out.”

“Mom,” I say. “Just don’t freak out.”

“Don’t freak out?” Her hands are on her hips now. “What’s going on? I’m getting a very strange vibe here.” Keeping her eyes on me, she stalks into the kitchen and turns on the TV.

“Mom,” I groan, but it’s too late. When I get to the TV to stand beside her, I see flashing police lights, and in the corner, Will and Chase’s class photos. So the story broke. Cops and reporters are flooding across the lawn like ants to a sandwich crust, ready to break it down and carry it away for consumption.

“What is this?” She puts her hand to her mouth. “Oh, Cas, did you know those boys? Oh, how awful. Is that why you’re out of school? Did they shut it down for the day?”

She is trying very hard not to look me in the face. She spit out those civilian questions, but she knows the real score. And she can’t even con herself. After a few more seconds, she shuts the TV back off and nods her head slowly, trying to process.

“Tell me what’s happened.”

“I don’t know quite how.”

“Try.”

So I do. I leave out as many details as I can. Except for the bite wounds. When I tell her about those, she holds her breath.

“You think it was the same?” she asks. “The one that—”

“I know it was. I can feel it.”

“But you don’t know.”

“Mom. I know.” I’m trying to say this stuff gently. Her lips are pressed together so tightly that they’re not even lips anymore. I think she might cry or something.

“You were in that house? Where’s the athame?”

“I don’t know. Just, stay calm. We’re going to need your help.”

She doesn’t say anything. She’s got one hand on her forehead and the other on her hip. She’s looking off into nothing. That deep little wrinkle of distress has appeared on her forehead.

“Help,” she says softly, and then one more time, only harder. “Help.”

I might have put her into some kind of overload coma.

“Okay,” I say gently. “Just stay here. I’ll get this handled, Mom. I promise.”

Anna’s waiting outside, and who knows what’s happening back at the shop. It seems like I’ve taken hours on this errand, but I can’t have been gone more than twenty minutes.

“Pack your things.”

“What?”

“You heard me. Pack your things. This instant. We’re leaving.” She pushes past me and flies up the stairs, presumably to get started. I follow with a groan. There’s no time for this. She’s going to have to calm down and stay put. She can pack me up and toss my stuff into boxes. She can load it into a U-Haul. But my body is not leaving until this ghost is gone.

“Mom,” I say, going after the last of her trailing sweater into my bedroom. “Will you stop flipping out? I’m not leaving.” I pause. Her efficiency is unmatched. All of my socks are already out of my drawer and set in an ordered stack on my dresser. Even the striped ones are to one side of the plain.

“We are leaving,” she says without missing a beat in her ransacking of my room. “If I have to knock you unconscious and drag you from this house, we are leaving.”

“Mom, settle down.”

“Do not tell me to settle down.” The words are delivered in a controlled yell, a yell straight from the pit of her tensed stomach. She stops and stands still with her hands in my half-emptied drawers. “That thing killed my husband.”

“Mom.”

“It’s not going to get you, too.” Hands and socks and boxer shorts start flying again. I wish she hadn’t started with my underwear drawer.

“I have to stop it.”

“Let someone else do it,” she snaps. “I should have told you this before; I should have told you that this wasn’t your duty or your birthright or anything like that after your father died. Other people can do this.”

“Not that many other people,” I say. This is making me mad. I know she isn’t trying to, but I feel like she’s dishonoring my dad. “And not this time.”

“You don’t have to.”

“I choose to,” I say. I’ve lost the battle to keep my voice down. “If we go, it follows. And if I don’t kill it, it eats people. Don’t you get it?” Finally, I tell her what I’ve always kept secret. “This is what I’ve waited for. What I’ve trained for. I’ve been researching this ghost since I found the voodoo cross in Baton Rouge.”

Читать дальше