'I've come all this way with you,' Gillson reminded him, 'and it wasn't to get scared at the last moment.'

'Do you want to see now? You know once you've seen, the tactile delusions won't ever operate again — are you sure you can live with it?'

'For God's sake, yes!' Gillson's answer was barely audible.

'All right. I'm turning on the lights— now! '

When the police arrived at the flats on Tudor Street, where they had been summoned by a hysterical tenant, they found a scene which horrified the least squeamish among them. The tenant, returning from a late party, had only seen Kevin Gillson's corpse lying on the carpet, stabbed to death. The police were not sickened by this, however, but by what they found on the lawn under the broken front window; for Henry Fisher had died there, with his throat torn out by glass slivers from the pane.

It all seemed very extraordinary, and the tape-recorder did not help. All that it definitely told them was that some kind of black magic ritual had been practised that night, and they guessed that Gillson had been killed with the pointed end of the icon rod. The rest of the tape was full of esoteric references, and towards the end it becomes totally incoherent. The section after the click of the light-switch on the recording is what puzzles listeners most; as yet nobody has found any sane reason for Fisher's murder of his guest.

When curious detectives play the tape, Fisher's voice always comes: 'There — hell, I can't see after all that darkness. Now, what…

'My God, where am I? And where are you? Gillson, where are you — where are you? No, keep away — Gillson, for Christ's sake move your arm. I can see something moving in all this — but God, that mustn't be you… Why can't I hear you — but this is enough to strike anyone dumb… Now come towards me — my God, that thing is you — expanding — contracting — the primal jelly, forming and changing — and the colour… Get away! Don't come any closer — are you mad? If you dare to touch me, I'll let you have the point of this icon — it may feel wet and spongy and look — horrible — but it'll do for you! No, don't touch me — I can't bear to feel that—'

Then comes a scream and a thud. An outburst of insane screaming is cut short by the smashing glass, and a terrible choking sound soon fades to nothing.

It is amazing that two men should have seemingly deluded themselves into thinking they had changed physically; but such is the case, for the two corpses were quite unchanged except for their mutilations. Nothing in the case cannot be explained by the insanity of the two men. At least, there is one anomaly; but the chief of the Camside police is certain that it is only a fault in the tape which causes the recorder to emit, at certain points, a loud dry rustling sound.

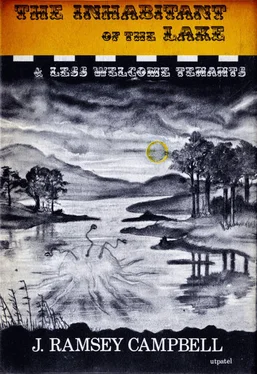

The Inhabitant of the Lake

After my friend Thomas Cartwright had moved into the Severn valley for suitable surroundings in which to work on his macabre artwork, our only communication was through correspondence. He usually wrote only to inform me of the trivial happenings which occur in a part of the countryside ten miles from the nearest inhabited dwelling, or to tell me how his latest painting was progressing. It was, then, somewhat of a departure from the habitual when he wrote to tell me of certain events — seemingly trivial but admittedly puzzling — which culminated in a series of unexpected revelations.

Cartwright had been interested in the lore of the terrible ever since his youth, and when he began to study art his work immediately exhibited an extremely startling morbid technique. Before long, specimens were shown to dealers, who commended his paintings highly, but doubted that they would appeal to the normal collector, because of their great morbidity. However, Cartwright's work has since been recognised, and many aficionados now seek originals of his powerful studies of the alien, which depict distorted colossi striding across mist-enshrouded jungles or peering round the dripping stones of some druidic circle. When he did begin to achieve recognition, Cartwright decided to settle somewhere which would have a more fitting atmosphere than the clanging London streets, and accordingly set out on a search through the Severn area for likely sites. When I could, I accompanied him; and it was on one of the journeys when we were together that an estate agent at Brichester told him of a lonely row of six houses near a lake some miles to the north of the town, which he might be interested in, since it was supposed to be haunted.

We found the lake easily enough from his directions, and for some minutes we stood gazing at the scene. The ebon depths of the stagnant water were surrounded by forest, which marched down a number of surrounding hills and stood like an army of prehistoric survivals at the edge. On the south side of the lake was a row of black-walled houses, each three storeys high. They stood on a grey cobbled street which began and ended at the extremities of the row, the other edge disappearing into the pitchy depths. A road of sorts circled the lake, branching from that patch of street and joining the road to Brichester at the other side of the lake. Large ferns protruded from the water, while grass grew luxuriantly among the trees and at the edge of the lake. Although it was midday, little light reached the surface of the water or touched the house-fronts, and the whole place brooded in a twilight more depressing because of the recollection of sunlight beyond.

'Looks like the place was stricken with a plague,' Cartwright observed as we set out across the beaded stones of the segment of road. This comparison had occurred to me also, and I wondered if my companion's morbid trait might be affecting me. Certainly the desertion of this forest-guarded hollow did not evoke peaceful images, and I could almost visualise the nearby woods as a primeval jungle where vast horrors stalked and killed. But while I was sympathetic with Cartwright's feelings, I did not feel pleasure at the thought of working there — as he probably did — rather dreading the idea of living in such an uninhabited region, though I could not have said why I found those blank house-fronts so disquieting.

'Might as well start at this end of the row,' I suggested, pointing to the left. 'Makes no difference as far as I can see, anyway — how are you going to decide which one to take? Lucky numbers or what? If you take any, of course.'

We had reached the first building on the left, and as we stood at the window I could only stare and repeat 'If any.' There were gaping holes in the bare floorboards in that room, and the stone fireplace was cracked and cobwebbed. Only the opposite wall seemed to be papered, and the yellowed paper had peeled off in great strips. The two wooden steps which led up to the front door with its askew knocker shifted alarmingly as I put my foot on the lower, and I stepped back in disgust.

Cartwright had been trying to clear some of the dust from the window-pane, but now he left the window and approached me, grimacing. 'I told him I was an artist,' he said, 'but that estate agent must think that means I live in the woods or something! My God, how long is it since anyone lived in one of these?'

'Perhaps the others may be better?' I guessed hopefully.

'Look, you can see from here they're all as bad,' complained Cartwright.

His complaint was quite true. The houses were very similar, surprisingly because they seemed to have been added to at various periods, as if they were always treated alike; all had unsightly stone roofs, there were signs that they might once have been half-timbered, they had a kind of bay window facing on to the street, and to the door of each led the creaking wooden steps. Although, now I came to stand back, and look up the row, the third from the left did not look as uninviting as the others. The wooden steps had been replaced by three concrete stairs, and I thought I saw a doorbell in place of the tarnished knocker. The windows were not so grimy, either, even though the walls were still grey and moist. From where I stood the lake's dim reflection prevented me from seeing into the house.

Читать дальше