As it had been for more years than he liked to think about, the news was sprinkled liberally with insanity, with signs of a society enduring a prolonged attack of schizophrenia. In Detroit three men had been killed when a group of young Marxist factory workers, all of whom earned salaries that provided them with a Cadillac-standard of living, planted a bomb under a production-line conveyor belt. In Boston, an organization calling itself The True Sons of America was taking credit for a bomb explosion in the offices of a liberal newspaper, where a secretary and bookkeeper were killed. And in California the left-wing Symbionese Liberation Army had surfaced once again. Eight SLA “soldiers” had crashed a birthday party in a wealthy San Francisco suburb and murdered two adults and five small children. They had kidnapped three other children, leaving behind a tape recording which explained that after much consideration and discussion among themselves about what would be best for the People, they had decided to stop the capitalist machine by either murdering or “reeducating” its children. Therefore, they had kidnapped three children for reeducation and had slaughtered those for whom they had no available SLA foster parents.

McAlister picked up his bourbon and finished nearly half of it in one long swallow.

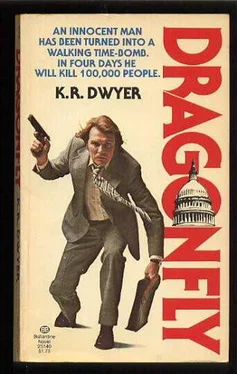

In the past he had read this sort of news and had been appalled; now he was outraged. His hands were shaking. His face felt hot, and his throat was tight with anger. These SLA bastards were no different from the crackpots who were behind the Dragonfly project. One group was Marxist and one fascist, but their methods and their insensitivity and their self-righteousness and even their totalitarian goals were substantially the same. Was it possible for even the most single-minded liberal to support fair trial, mercy, and parole for these bastards? Was it possible for anyone to try to explain their behavior as having its source in poverty and injustice? Was it possible, even now, for anyone to express equal sympathy for killers and victims alike? He wished it were possible to execute these people without trial… But that would be playing right into the hands of men like A. W. West — who, of course, deserved the same treatment, the same quick and brutal punishment, but who would probably wind up administering it to the left-wingers. None of these people, revolutionaries or reactionaries, deserved to live among men of reason. They were all animals, throwbacks, forces for chaos who had none but a disruptive function in a civilized world. They should be sought, apprehended, and destroyed—

Yes, but how in the hell did that sort of thinking mesh with his well-known liberalism? How could he believe in the reasonable world his Boston family and teachers had told him about — and still believe in meeting violence with violence?

He quickly finished the last of his bourbon.

“Bad day, was it?”

McAlister looked up and saw Fredericks, an assistant attorney general at the Justice Department, standing in front of his table.

“I thought you were pretty much a teetotaler,” Bill Fredericks said.

“Used to be.”

“You ought to get out of the CIA.”

“And come over to Justice?”

“Sure. We whittle away hours on anti-trust suits. And even when we've got a hot case, we aren't rushed. The wheels of justice grind slowly. One martini a night eases the tension.”

Smiling, McAlister shook his head and said, “Well, if you've got it so damned easy over there, I wish you'd make an effort to help take the pressure off me when you get the chance.”

Fredericks blinked. “What'd I do?”

“It's what you didn't do.”

“What didn't I do?'

McAlister reminded him of how long he'd taken to send that list of federal marshals to Andrew Rice.

“But that's not true,” Fredericks said. “Rice's secretary called and asked for the list. No explanations. Very snotty. Wanted to have it sooner than immediately. National security. Fate of the nation at stake. Future of the free world in the balance. Danger to the republic. That sort of thing. I couldn't get hold of a messenger fast enough, so I sent my own secretary to deliver it. She left it with Rice's secretary.” He stopped and thought for a moment. “I know she was back in my office no later than four o'clock.”

McAlister frowned. “But why would Rice lie to me?”

“You'll have to ask him.”

“I guess I will.”

“If you're dining alone,” Fredericks said, “why don't you join us?” He motioned to a table where two other lawyers from Justice were ordering drinks.

“Bernie Kirkwood is supposed to join me before long,” McAlister said. “Besides, I wouldn't be very good company tonight.”

“In that case, maybe I better join you, Bill,” Kirk-wood said as he arrived at McAlister's table.

Kirkwood was in his early thirties, a thin, bushy-headed, narrow-faced man who looked as if he'd just been struck by lightning and was still crackling with a residue of electricity. His large eyes were made even larger by thick gold-framed glasses. His smile revealed a lot of crooked white teeth.

“Well,” Fredericks said, “I can't let any newsmen see me with both of you crusaders. That would start all sorts of rumors about big new investigations, prosecutions, heads rolling in high places. My telephone would never stop ringing. How could I ever find the time I need to nail some poor bastard to the wall for income-tax evasion?”

Kirkwood said, “I didn't know that you guys at Justice ever nailed anyone for anything.”

“Oh, sure. It happens.”

“When was the last time?”

“Six years ago this December, I think. Or was it seven years last June?”

“Income-tax evader?”

“No, I think it was some heinous bastard who was carrying a placard back and forth in front of the White House, protesting the war. Or something.”

“But you got him,” Kirkwood said.

“Put him away for life.”

“We can sleep nights.”

“Oh, yes! The streets are safe!” Grinning, Fredericks turned to McAlister and said, “You'll check that out — about the list? I'm not lying to you.”

“I'll check it out,” McAlister said. “And I believe you, Bill.”

Fredericks returned to his own table; as he was leaving, the waiter brought menus for McAlister and Kirkwood, took their orders for drinks, fetched one bourbon and one Scotch, and said how nice it was to see them.

When they were alone again, Kirkwood said, “We found Dr. Hunter's car in a supermarket parking lot a little over a mile from his home in Bethesda.”

Dr. Leroy Hunter, McAlister knew, was another biochemist who had connections with the late Dr. Olin Wilson. He had also been on friendly terms with Potter Cofield, their only other lead, the man who had been stabbed to death in his own home yesterday. He said, “No sign of Hunter, I suppose.”

Kirkwood shook his woolly head: no. “A neighbor says she saw him putting two suitcases in the trunk of the car before he drove away yesterday afternoon. They're still there, both of them, full of toilet articles and clean clothes.”

Sipping bourbon, leaning back in his chair, McAlister said, “Know what I think?”

“Sure,” Kirkwood said, folding his bony hands around his glass of Scotch. “Dr. Hunter has joined Dr. Wilson and Dr. Cofield in that great research laboratory in the sky.”

“That's about it.”

“Sooner or later we'll find the good doctor floating face-down in the Potomac River — a faulty electric toaster clasped in both hands and a burglar's knife stuck in his throat.” Kirkwood grinned humorlessly.

“Anything on those two dead men we found in David Canning's apartment?”

“They were each other's best friend. We can't tie either of them to anyone else in the agency.”

Читать дальше